![Pow!]()

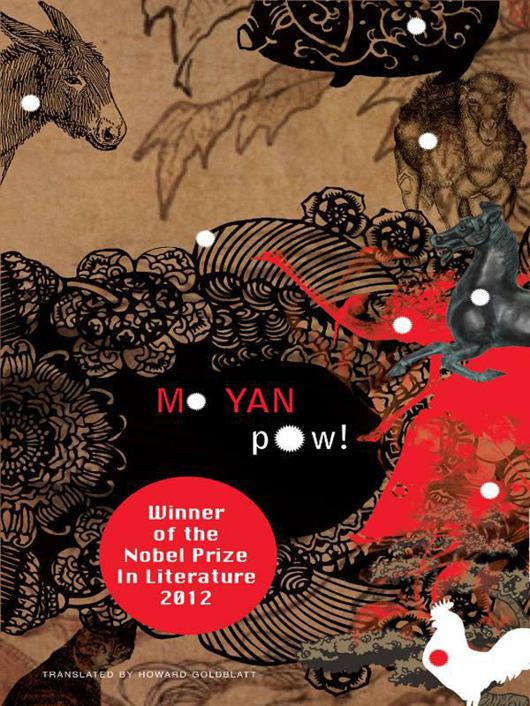

Pow!

turn longed for it. Once I'd fired my forty-one shells, I'd be a powboy of legend, a part of history.

An unlocked gate allowed us entry into our yard, where we were welcomed by dancing weasels. I knew that my yard was a weasel playground now, a place where they fell in love, married and multiplied in numbers sufficient to keep out scavengers. Weasels have a charm that women find irresistible; they make them take leave of their senses and provoke them into singing and dancing and, in some cases, even running naked down the street. But they didn't scare us. ‘Thanks, guys,’ I said to them, for guarding the mortar for me. ‘You're welcome,’ they replied. Some wore red vests, like runners on the stock-exchange floor. Others had on white shorts, like children at a public swimming pool.

First we took apart the mortar in the side room and carried the parts into the yard. Then, after leaning a ladder against the eaves of the westside room, I climbed onto the roof. The roof tiles on the neighbourhood houses glinted in the moonlight. I could see the river flowing behind the village, the open fields in front and the fires burning in the wild. I couldn't have asked for a more opportune moment. Why wait? I asked my companions to tie each part with a rope, and tie it well, so that I could then haul it up onto the roof. I removed a pair of white gloves from the tube, put them on and then swiftly reassembled the weapon; before long, my very own mortar crouched on the roof, gleaming in the moonlight, like a bride emerged from her bath and waiting for her new husband. Pointed into the sky at a forty-five-degree angle, the tube seemed to suck up the moonbeams. Several playful weasels climbed up beside me, scurried across to the mortar and began to scratch at it. They were so cute that I didn't stop them. Had it been anyone else I'd have thrown them off without a second thought. Then the boy led the mule up to the foot of the ladder and the old couple unloaded the cases, moving with precision and confidence. Even one shell dropped to the floor would have meant disaster. Each case was tied with rope; I hauled them up, one at a time, and then laid them out on the roof. That done, the old couple and the little boy climbed up to join me. The woman was gasping for breath by then. She suffered from an inflamed windpipe, and I knew she needed to eat a turnip to feel better. If only we had one. ‘We'll take care of that,’ one of the weasels said. Before long, eight little creatures scrambled up the ladder, chanting a rhythmic hi-ho, carrying a turnip two feet long and with a high water content. The old man rushed up to lift it from the weasels’ shoulders and hand it to his wife. Then he thanked them profusely, a manifestation of the common man's simple manners. The old woman broke the turnip in half over her knee, laid the bottom half beside her, took a crisp bite out of the top and then began to chew, suffusing the moonbeams with the smell of turnip.

‘Fire a round!’ she said. ‘Eating a turnip dipped in gunpowder smoke will cure me. Sixty years ago, when my son was born, five Japanese soldiers shot a mortar in our yard, sending gunpowder smoke in through the window and into my throat, damaging my windpipe. I've had asthma ever since, and my son was so badly shaken by the explosions and choked by the smoke that it weakened his constitution and killed him.’

‘The five men who did that got the death they deserved,’ continued the old man. ‘They killed our little cow, then chopped up and burnt our furniture to make a fire to roast it in. But it was only partially cooked, and they all died of salmonella poisoning. So we hid the mortar in the woodpile and the seven cases in a hollow between the walls. Then we escaped up Southern Mountain with our son's body. Later, people came looking for us, calling us heroes for poisoning the meat of our cow and killing five of those devils. We weren't heroes—those devils had had us shaking in our boots. And we certainly hadn't poisoned the meat. The sight of them writhing on the ground had brought us no pleasure at all. In fact, my wife, who was still ill, had boiled a pot of mung-bean soup for them. Usually that's a good cure for poison but theirs ran too deep in their bodies and they could not be saved. Years later, another man showed up and insisted we admit to killing them. A militiaman, he'd stabbed an enemy officer in the back with a muck rake while he took a shit. He'd then

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher