![Praying for Sleep]()

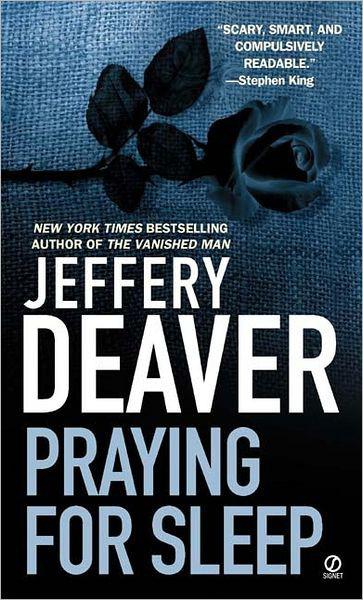

Praying for Sleep

intimate and hating, and whose mother dared to be truly present only when her man was not. Lis could not refuse the covert pleas for help—like the times the girl stayed after class to ask intelligent if calculated questions about Jacobean drama, or happened—too coincidentally—to find herself walking beside her teacher on the deserted riverside behind the school.

Lis was again picturing Claire’s face when she realized that the psychiatrist was asking her a question. He wanted to know about the trial.

“The trial?” she repeated softly. “Well, I got to the courthouse early . . .”

“Just you?”

“I refused to let Owen come with me. It’s hard to explain but I wanted to keep what happened at Indian Leap as separate as possible from my home. Owen spent the day with Dorothy. After all, she was the widow. She needed comforting more than I.”

Inside the courtroom, when Lis first saw Hrubek—it’d been five and a half weeks since the murder—he looked smaller than she recalled. He was pale, sickly. He squinted at her and his mouth twisted into an eerie smile. As she walked down the aisle Lis tried to keep her eyes on the prosecutor, a young woman with a mass of flyaway hair. She’d been prepping Lis all week for the court appearance. Lis sat behind her but in full view of Hrubek. His hands were manacled in front of him and he lifted them as far as he could then simply stared at her, his lips moving compulsively.

“God, it was eerie.”

“That’s just dyskinesia,” Kohler explained. “It’s a condition caused by antipsychotic drugs.”

“Whatever, it was scary as hell. When he spoke he almost gave me a heart attack. He jumped up and said, ‘Conspiracy!’ And ‘Revenge,’ or something. I don’t remember exactly.”

Apparently these outbursts had happened before, because everyone, including the judge, ignored him. As she walked past he grew very calm and asked her in a conversational tone if she knew where he was on the night of April 14 at 10:30 p.m.

“April 14 ?”

“That’s right.”

“And the murder was May 1, wasn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“Did April 14 mean anything to you?”

She shook her head. A small notation went into Kohler’s book. “Please go on.”

“Hrubek said, ‘I was murdering somebody. . . .’ I’m not quoting exactly. Something like, ‘I was murdering somebody. The moon rose blood red and ever since that day I have been the victim of a conspiracy—’ ”

“Lincoln’s assassination!” Kohler looked at her with raised eyebrows.

“I’m sorry?”

“Didn’t it happen in mid-April?”

“I think it was around then, yes.”

Another notation.

With disdain Lis observed the brief smile that crossed Kohler’s lips then she continued, “He was saying, ‘I’ve been implanted with tracking and listening devices. I’ve been tortured.’ Sometimes he was incoherent, sometimes he sounded like a doctor or lawyer.”

Lis was the main prosecution witness. She swore her oath then settled in a huge wooden chair. On its seat was a crocheted cushion and she wondered if it had been made by the wife of the grizzled, slouching judge. “The prosecutor asked me to tell the court what happened that day. And I did.”

Her testimony seemed to take an eternity. She later learned she was in the spotlight for all of eight minutes.

She was dreading cross-examination by the defense attorney. But she wasn’t called. Hrubek’s lawyer said simply, “No questions,” and she spent the next several hours in the gallery.

“All I could do was stare at the plastic bags that contained the rock stained with Robert’s blood, and the kitchen knife. I sat in the back of the courtroom with Tad. . . .” Kohler lifted an inquiring eyebrow. “He’s a former student of mine. He does work for me around the yard and greenhouse. I told everybody I knew not to attend the trial. But Tad ignored me. He was there all day long, cheerful and smiling. We sat together.”

Before she testified, the young man found her in the corridor outside and handed her a paper bag. Inside was a yellow rose. He’d trimmed the thorns and cut the stem back, wrapped it in wet paper towels. Lis had cried and kissed him on the cheek.

“Was it a long trial?” Kohler asked.

Not really, she explained. The defense lawyer didn’t dispute the fact that Hrubek had killed Robert. He relied on the insanity defense—Hrubek lacked the mental state to understand that his acts were criminal. Under the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher