![Praying for Sleep]()

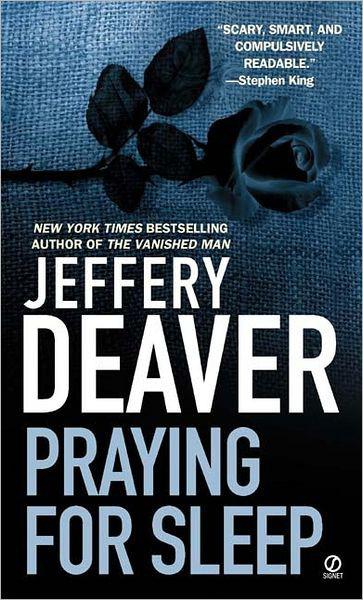

Praying for Sleep

M’Naghten rule, Lis relayed to Kohler what she’d learned during the jury instruction, the death becomes an act of God. The lawyer didn’t even put Hrubek on the stand. He offered medical reports and depositions, which were read out loud by a clerk. This all had to do with Hrubek’s inability to appreciate the consequences of his actions.

All that time the madman had sat at the defense table, hunched over, twining his dirty hair between blunt fingers, laughing and muttering, filling sheet after sheet of foolscap with tiny frantic characters and lines. She hadn’t paid any attention to these doodlings then but understood later that he hadn’t been as crazy as it appeared—this was undoubtedly how he’d recorded her name and address.

A verdict of not guilty by reason of diminished capacity was entered. Under Section 403 of the Mental Health Law, Hrubek would be classified as dangerously insane and would be incarcerated indefinitely in a state hospital, to be reevaluated annually.

“I left the courthouse. Then—”

“And what about the incident,” Kohler asked, palms meeting as if he were clapping in slow motion, “with the chair?”

“Chair?”

“He jumped up on a chair or table.”

Ah, yes. That.

The courtroom began to empty. Suddenly a huge voice rose over the murmuring of the spectators and press. Michael Hrubek was shouting. He threw a bailiff to the ground and climbed onto his chair. The manacles clanked and he lifted his arms over his head. He began screaming. His eyes met Lis’s for a moment and she froze. Guards subdued Hrubek, and a bailiff hustled her out of the courtroom.

“What did he say?”

“Say?”

“When he was on the chair. Did he shout anything?”

“I think he was just howling. Like an animal.”

“The article said he shouted, ‘You’re the Eve of betrayal. ’ ”

“Could be.”

“You don’t remember?”

“No. I don’t.”

Kohler was shaking his head. “Michael had therapy sessions with me. Three times a week. During one he said, ‘Betrayal, betrayal. Oh, she’s courting disaster. She sat in that court, and now she’s courting disaster. All that betrayal. Eve’s the one.’ When I asked him what he meant, he became agitated. As if he’d let an important secret slip. He wouldn’t talk about it. He’s mentioned betrayal several times since then. You have any thoughts on what it might mean?”

“No. I don’t. I’m sorry.”

“And afterwards?”

“After the trial?” Lis sipped the strong coffee. “Well, I took a trip to hell.”

After the publicity faded and Hrubek was committed in Marsden, Lis resumed the life she’d led before the tragedy. At first her routine seemed largely unchanged—teaching summer school, spending Sundays at the country club with Owen, visiting friends, tending the garden. She was perhaps the last person to notice that her life was unraveling.

Occasionally she’d skip a shower. She’d forget the names of guests attending her own cocktail parties. She might happen to glance down as she walked through the corridors of the school and find that she was wearing mismatched shoes. She’d teach Dryden instead of the scheduled Pope and berate students for failing to read material she’d never assigned. Sometimes in lectures and in conversations she found herself gazing at embarrassed, perplexed faces and could only wonder what on earth she’d just uttered.

“It was as if I was sleepwalking.”

She withdrew into her greenhouse and mourned.

Owen, patient initially, grew tired of Lis’s torpor and absentmindedness and they began to fight. He spent more time on business trips. She stayed home more and more frequently, venturing outside only for her classes. Her sleep problems grew worse: it was not unusual for her to remain awake for twenty-four hours straight.

Adding to Lis’s difficulty was Dorothy, who stepped as brusquely into widowhood as she slipped into the front seat of her Mercedes SL. She was gaunt and pale and didn’t smile for two months. Yet she functioned, and functioned quite well. Owen several times held her out as an example of someone who took tragedy in stride. “Well, I’m not like her, Owen. I never have been. I’m sorry.”

When Dorothy sold her house and moved to the Jersey shore in July, it was not she but Lis who cried during their farewell lunch.

Lis’s life became school and her greenhouse, where she would snip plants and wander like a lost child over the slate path, her face

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher