![Ptolemy's Gate]()

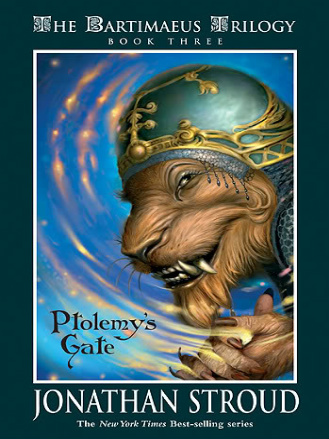

Ptolemy's Gate

flatter. Why? Because on top of me was an upturned building. Its weight bore down. Muscles strained, tendons popped; try as I might, I could not push free.

In principle there's nothing shameful about struggling when a building falls upon you. I've had such problems before; it's part of the job description.[1] But it does help if the edifice in question is glamorous and large. And in this case, the fearsome construction that had been ripped from its foundations and hurled upon me from a great height was neither big nor sumptuous. It wasn't a temple wall or a granite obelisk. It wasn't the marbled roof of an emperor's palace.

[1] There was the time when a small section of Khufu's Great Pyramid collapsed upon me one moonless night during the fifteenth year of its construction. 1 was guarding the zone that my group was working on, when several limestone blocks tumbled down from the top, transfixing me painfully by one of my extremities. Exactly how it happened was never resolved, though my suspicions were directed at my old chum Faquarl, who was working with a rival group on the opposite side. I made no outward complaint, but bided my time while my essence healed. Later, when Faquarl was returning across the Western Desert with some Nubian gold, I invoked a mild sandstorm, causing him to lose the treasure and incur the pharaoh's wrath. It took him a couple of years to sift all the pieces from the dunes.

No. The object that was pinning me haplessly to the ground, like a butterfly on a collector's tray, was of twentieth-century origin and of very specific function.

Oh, all right, it was a public lavatory. Quite sizable, mind, but even so. I was glad no harpers or chroniclers happened to be passing.

In mitigation, I must report that the lavatory in question had concrete walls and a very thick iron roof, the cruel aura of which helped weaken my already feeble limbs. And there were doubtless various pipes and cisterns and desperately heavy taps inside, all adding to the total mass. But it was still a pretty poor show for a djinni of my stature to be squashed by it. In fact, the abject humiliation bothered me more than the crushing weight.

All around me the water from the snapped and broken pipework trickled away mournfully into the gutters. Only my head projected free of one of the concrete walls; my body was entirely trapped.[2]

[2] The obvious solution would have been to change form—into a wraith, say, or a swirl of smoke, and just drift clear. But there were two problems. One: I found it hard to change shape these days, very hard, even at the best of times. Two: the considerable downward pressure would have blown my essence apart the moment I softened it to make the change.

So much for the negatives. The good side was that I was unable to rejoin the battle that was taking place up and down the suburban street.

It was a fairly low-key sort of battle, especially on the first plane. Nothing much could be seen. The house lights were all out, the electric street lamps had been tied in knots; the road was dark as an inkstone, a solid slab of black. A few stars shone coldly overhead. Once or twice indistinct blue-green lights appeared and faded, like explosions far off underwater.

Things hotted up on the second plane, where two rival flocks of birds could be seen wheeling and swooping at each other, buffeting savagely with wings, beaks, claws, and tails. Such loutish behavior would have been reprehensible among seagulls or other down-market fowl; the fact that these were eagles made it all the more shocking.

On the higher planes the bird guises were discarded altogether, and the true shapes of the fighting djinn came into focus.[3] Seen from this perspective, the night sky was veritably awash with rushing forms, contorted shapes, and sinister activity.

[3] Truer, anyway. At bottom, we are all alike in our seeping formlessness, but every spirit has a "look" that suits them, and which they use to represent themselves while on Earth. Our essences are molded into these personal shapes on the higher planes, while—on the lower ones—we adopt guises that are appropriate to the given situation. Listen, I'm sure I've told you all this before.

Fair play was entirely disregarded. I saw one spiked knee go crunching into an opponent's belly, sending him spinning away behind a chimney to recover. Disgraceful! If I'd been up there I'd have had no truck with that.[4]

[4] I'd have kneed him first, then stuck a wingtip in his

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher