![Ptolemy's Gate]()

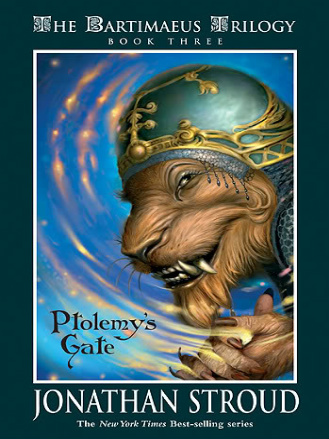

Ptolemy's Gate

drawn to it as a child to a window. She had been sitting safely in the center of her pentacle. Now she half uncrossed her legs and leaned forward, supporting herself on one arm, stretching out the other, reaching up slowly toward the eyes, toward their solitude and emptiness. Her fingertips trembled above the fringes of her circle; she sighed, hesitated, reached out. . .

The boy blinked, his eyelids flicking like a lizard's. The spell was broken. Kitty's skin crawled; her hand jerked back. She shrank into the center of the circle, fresh sweat beading on her brow. Still the boy did not move.

"What do you presume," a voice said, "to know about me?"

It had sounded all around her—not loudly, but very near at hand—a voice different from any that she had heard before. It spoke in English, but the inflection was odd, as if the tongue found the language alien and strange; it sounded close, but also not so, as if dredged up from some incalculable distance.

"What do you know?" the voice said again, quieter than before. The djinni's lips were still, the black eyes locked on her. Kitty hunched herself against the floor, trembling, teeth clenched together. Something in the voice unmanned her, but what? It did not speak violently or with anger, quite. But it was a voice of power from a far-off place, a voice of terrible command, and it was a child's voice too.

She lowered her head and shook it dumbly, gazing at the floor.

"TELL ME!" Now there was anger in the voice; as it spoke, a great noise sounded in the room—a thunderclap that shook the window and rippled out across the floorboards, sending chips of rotten plaster dropping from the walls. The door slammed shut (but she had not opened it, nor seen it open); the window shattered and fell away. At the same time a great wind rose up around the chamber, whirling all about her, faster and faster, sending the bowls of rosemary and rowan wood flying, slamming them out against the walls, seizing the book and the candlesticks, her satchel and her coat, carrying them high and low around the room, whistling and wailing, around and around and around until they blurred. And now the very walls were moving too, tearing from their sockets in the floor and joining in the frenzied dance, spitting bricks loose as they spun, spiraling around and around beneath the ceiling. And finally the ceiling was gone, and the awful immensity of the night sky stretched above, with stars and moon spinning and the clouds being drawn out into pale white threads that shot in all directions, until the only still points in all the universe were Kitty and the boy inside their circles.

Kitty clapped her fingers across her eyes and buried her head between her knees.

"Please stop," she cried. "Please!"

And the tumult ceased.

She opened her eyes; saw nothing. Her hands were still clamped to her face.

With stiff and painful care, she raised her head and lowered her hands. The room was exactly as before, as it had always been: door, book, candlesticks and window, walls, ceiling, floor; beyond the window, a placid sky. All was quiet, except . . . the boy in the opposing pentacle was moving now, bending his legs slowly, slowly—then sitting with abrupt finality, as if all the energy had gone out of him. His eyes were closed. He passed a hand wearily in front of his face.

He looked at her then, and the eyes, though dark, had nothing of their former emptiness. When he spoke, his voice was back to normal, but it sounded tired and sad. "If you're going to summon djinn," he said, "you summon their history with them. It's wise to keep matters firmly in the present, for fear of what you might awaken."

With great difficulty, Kitty forced herself to sit upright and face him. Her hair was wet with perspiration; she ran a hand through it and wiped her forehead. "There was no need for that. I merely mentioned—"

"A name. You ought to know what names can do."

Kitty cleared her throat. The first surge of fright was wearing off, to be fast replaced with a teary feeling. She fought it down. "If you're so keen to keep matters in the present," she gulped furiously, "why do you persist in wearing. . . his form?"

The boy frowned. "You're a little too clever today, Kitty. What makes you think I'm wearing anyone's guise? Even in my weakened state I can look how I please."Without stirring, he changed shape once, twice, half a dozen times, each form more startling than the last, each one sitting in exactly the same position

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher