![Ptolemy's Gate]()

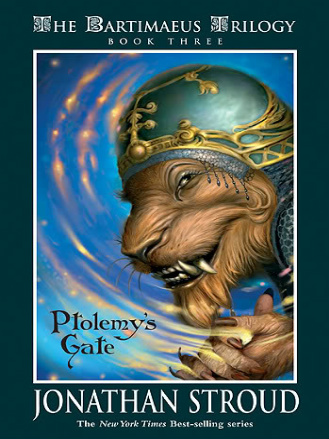

Ptolemy's Gate

my wing. Hopkins's form rose into the air and turned to face the darkened dining room. "Let's see," Faquarl murmured. "Yes. . . that looks promising." We drifted out above the tables, toward the opposite wall. A trolley stood there, just as the waiters had left it. On the center of the trolley was a large tureen with a domed lid. It was made of silver.

The crow wriggled and fidgeted desperately in its captor's grip. "Come on, Faquarl," I implored. "Don't do anything you might regret."

"I most certainly won't." He descended beside the trolley, held me above the tureen; the cold radiation of the fatal metal tickled against my ragged essence. "A healthy djinni might linger for weeks in a silver tomb like this," Faquarl said. "The state you're in, I don't think you'll survive longer than a couple of hours. Now then, I wonder what we've got in here. . ." With a hasty flick of the fingers he flipped open the lid."Hmm. Fish soup. Delightful. Well, good-bye, Bartimaeus. While you die, take consolation from the knowledge that the enslavement of the djinn is almost over. As of tonight, we take revenge."The fingers parted; with a delicate plop, the crow fell into the soup. Faquarl waved good-bye and closed the lid. I floated in darkness. Silver all around me: my essence shrank and blistered.

I had one chance—one chance only: wait a little for Faquarl to depart, then summon up my last gasps of energy and try to burst open the lid. It would be tough, but feasible—provided he didn't wedge it shut with a block or anything.

Faquarl didn't bother with a block. He went for the whole wall. There was a great roar and crash, a fearsome impact; the tureen collapsed around me, smashed into a crumpled mess by the weight of masonry above. Silver pressed on all sides; the crow writhed, wriggled, but had no space to move. My head swam, my essence began to boil; almost gratefully I fell into unconsciousness.

Burned and squashed to death in a silver vat of soup. There must be worse ways to go. But not many.

21

Nathaniel looked out of the window of the limousine at the night, the lights, the houses, and the people. They went by in a kind of blur, a mass of color and movement that changed endlessly, beguilingly, and yet meant nothing. For a while he let his tired gaze drift among the shifting forms, then—as the car slowed to approach a junction—he focused on the glass itself and on the reflection in it. He saw himself again.

It was not a wholly reassuring sight. His face was etched with weariness, his hair damp, his collar limply sagging. But in his eyes a spark still burned.

Earlier that day it had not been so. Successive crises—his humiliation at Richmond, the threats to his career, and the discovery of his earlier betrayal by Bartimaeus—had hit him hard. His carefully constructed persona of John Mandrake, Information Minister and blithely assured member of the Council, had begun to crack around him. But it had been his rejection by Ms. Lutyens that morning that had dealt the decisive blow. In a few moments of sustained contempt she had shattered the armor of his status and laid bare the boy beneath. The shock had been almost too much for Nathaniel; with the loss of self-esteem came chaos—he had spent the rest of the day locked in his rooms, alternately raging and subsiding into silence.

But two things had combined to draw him back, to prevent him drowning in self-pity. First, on a practical level, Bartimaeus's delayed report had given him a lifeline. News of Hopkins's whereabouts offered Nathaniel a final chance to act before the next day's trial. By capturing the traitor he might yet outmaneuver Farrar, Mortensen, and the rest of his enemies: Devereaux would forget his displeasure and restore Nathaniel to a position of prestige.

Such success was not guaranteed, but he was confident in the power of the djinn that he had sent to the hotel. And already he felt revived by the mere act of sending them. A warm feeling ran across his back, making him shudder a little in the confines of the car. At last he was being decisive once again, playing for the highest stakes, shrugging off the inertia of the last few years. He felt almost as he had done as a child, thrilling in the audacity of his actions. That was how it had often been, before politics and the stultifying role of John Mandrake had closed in on him.

And he no longer wished to play that part. True, if fate were kind, he would first ensure his political survival. But

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher