![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

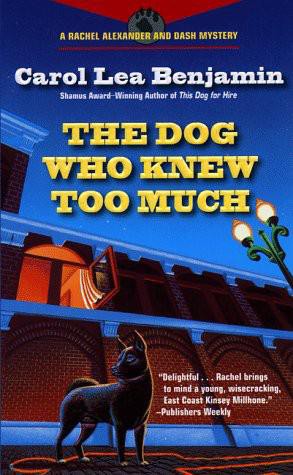

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

thyroid.” He made a fist and pointed to the floor with his thumb. “Way down. He and Gluck are taking the same pills now. We keep telling Gluck he better watch it, he’ll be out of a job, we’re going to put Elwood on the phone. The doc says it’ll take a few months for his weight to go down, but his energy is way up. You gotta see him. He’s like a new dog,” he said. “I’ll call you as soon as he gets back.”

The bomb dogs worked one week, then had two weeks off, what a lot of their fellow officers considered an enviable work schedule.

“You okay?”

I nodded.

“Good. That’s good. You take care now. And call me if you think of anything.”

It was nearly ten when I got back home, and I couldn’t remember having just walked across from the precinct. There were two more messages. Both hang-ups. Of course the calls hadn’t been from Marty. He would have left a message.

I sat in the living room for a while, thinking about Paul. There wouldn’t have been a wallet. When he’d paid for the Chinese food, his cash had been loose in his pocket. He wouldn’t go out without money. No one would. So the mugger had taken whatever cash he’d had on him.

I made a pot of tea, heating the pot with boiling water the way he had. But when it was ready and I’d carried my cup back to the couch, I just let it sit there, untouched.

He’d had the keys to the studio. Had he used them that night?

No, of course not. He wouldn’t have been so surprised to learn about the note if he had.

The phone rang, and I picked it up, but oddly, whoever was on the other end had nothing to say. That’s when it occurred to me that I couldn’t remember if I’d locked the garden gate. I grabbed my keys, put Lisa’s jacket back on, and walked outside, Dashiell following. We headed toward the dark tunnel that led to the gate. I was going to try it, to make sure it was locked. I was going to shake it, to see if it held, then finally go to sleep. But what I saw stuck in a curlicue of the wrought-iron gate stopped me dead in my tracks.

There, wrapped in floral paper with a layer of waxy green tissue paper underneath, were yellow rosebuds, twelve of them, each perfect. Their perfume filled the night air.

After making sure the gate was locked, I looked at the bouquet very carefully, even turning it upside down and shaking it. But no matter how hard I looked, I couldn’t find a card.

25

We Don’t Need the Money, He’d Said

THE PHONE RANG again. I could hear it as I carried the flowers back toward the cottage and laid them on the steps.

Someone had been sending roses for a while now. Someone had waited across the street from Lisa’s, watching her windows. And someone knew that I didn’t live at Lisa’s house, that I lived here. That when the time came, this is where I was to be found.

But it hadn’t been Paul. Then who was it? And what was he after now? Or who?

Leaving the roses on the steps, Dashiell in the garden, and the door open, I went upstairs, took the little stool from my office, and carried it into the bedroom closet. Then I climbed up on it and pulled down the Joan & David shoe box, a relic of my eight-month marriage to Dr. Fashion, a box much too heavy to have shoes in it, and put it on the bed.

Under some circumstances, my shrink Ida used to say, paranoia is not such an inappropriate response.

I went down to the basement where I had the formal dining room table I never used and all the cartons of stuff I’d never opened from when I split with Jack and moved here, saltcellars and linen napkins, a dozen sterling silver iced-tea spoons, stemware, Rosenthal china, wedding presents from people who apparently thought Jack had married Martha Stewart. I squeezed my way past a mountain of boxes to the sideboard against the far wall, which held only bullets for my gun and the boxes of gadgets Bruce Petrie used to give me, so full of formal dinnerparties was my life. With a box of thirty-eights in hand, I began to pick my way back to the stairs. But then I stopped.

Why was this stuff still here, still part of my life? More to the point, how had I fooled myself into thinking I could be happy spending my days hanging up the clothes someone else tossed over the dresser the night before and finding new things to do with cilantro?

I had moved into Jack’s Victorian house in Croton, overlooking the Hudson River , a sort of mirror image of Lili and Ted’s modem house on the other side of the river. Lili , cradling

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher