![Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much]()

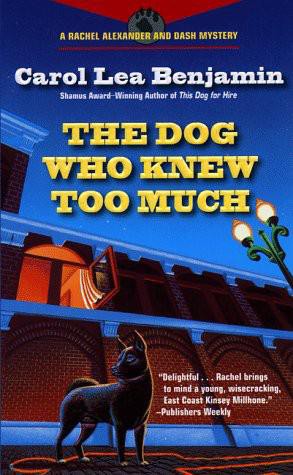

Rachel Alexander 02 - The Dog who knew too much

her morning coffee, could watch the sun rise over Westchester , pink turning to gold, all brightness and hope. I could watch the sun set over Rockland County , brilliant orange and flaming red, the colors of dying leaves in fall.

Having closed my dog school in the city, I’d figured, no problem, I’d train in Westchester , closer to home. But when I told Jack my plans, he became as still as marble and just as cold.

We don’t need the money, he’d said, as if that were all that work was about. Then, after a long frost, he spoke again. He wanted me home when he got home, not running around at all hours of the night getting myself bitten. He wanted to sit down to a nice, home-cooked meal with me and discuss his day. That’s what marriage was, wasn’t it, for chrissake , he’d said. He hadn’t married me, he added, to come home to an empty house.

Where, I remember wondering, was the man who’d found my occupation quirky and endearing? Get a load of this, he’d told his cretin brother Alan, she trains dogs for a living. And while I’d answered all his brother’s inane questions, he’d looked proud. But as soon as we were married, he’d changed.

The price of my poor judgment had been a divorce. Lisa’s may have cost her her life.

I put the box of bullets on the bottom step and began to open those other boxes, cartons containing carefully wrapped champagne flutes, a soup tureen, a fish poacher, grape shears, lobster forks. At three in the morning, having set aside only a hand-thrown planter I could use for herbs in the winter and a small, flowered bud vase, I resealed the cartons and stacked them neatly under the windows. Then I shut off the light, dropped the box of ammo in the kitchen, and went back out into the moonlit garden.

Alongside the house were the logs I had gathered last fall in the woods surrounding my sister’s house. The smaller pile, the split logs, was nearly gone. I tossed the jacket over that pile, lifted the heavy tarp from the larger woodpile, and unwrapped the sledgehammer and wedge that lay on top of the wood.

Dashiell lay peacefully on the rich, loamy earth near the oak tree that stretched skyward from the center of the garden. It was taller than the cottage. The moonlight, filtered through its branches, made his white fur look pearly, almost iridescent.

A mugging. Yeah, right.

Mid to late afternoon, I thought, lifting a log from the woodpile. Where had Howie been? It didn’t take an hour and a half to pick up a bottle of cheap Scotch for your mother, did it?

I stood the log on the tree stump near the wood pile and tapped in the wedge. Where had Stewie Fleck been between four and five? In the field, meaning anywhere he damn well wanted to be, the little creep?

What about Janet? Had she been at the gym, where Stewie said she practically lived, torturing innocents?

Come to think of it, where had Avi been? The news was full of reminders lately that no one is immune to human frailty, not judges, Nobel laureates, or even holy men.

If Paul had been killed across from the school, didn’t that mean he’d been on the way to the studio, to find me?

If so, why hadn’t he called to see if I were there?

But what would be the point? Surely he knew that no one ever picked up the phone. If someone doesn’t have the patience to wait for us to call them back, Avi had said once when I was going to answer the phone in the middle of working, they’re not going to have the patience to learn t’ai chi. Not answering the phone was a weeding-out process for him, the first in a long string of character tests.

Why Paul? I thought. But the answer to that question hit really close to home. Too close, if you ask me.

I looked back at Dashiell, still lying under the tree. Between his paws, right under his nose, he had serendipitously discovered a scent worthy of his complete attention. I could see his nostrils moving.

I turned my attention to the wood pile and began to split logs in earnest now, tapping the wedge into the next log, swinging the sledgehammer back and then high over one shoulder, bringing it down hard, hearing the satisfying clang of metal on metal and seeing the log cleave in two, opening like a flower that had suddenly decided to bloom, the outside darkened by the weather, the inside raw and vulnerable looking as a wound. I worked until I developed a rhythm, until I was drenched with sweat, until I no longer knew where the sledgehammer ended and I began, nor did I care,

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher