![Requiem for an Assassin]()

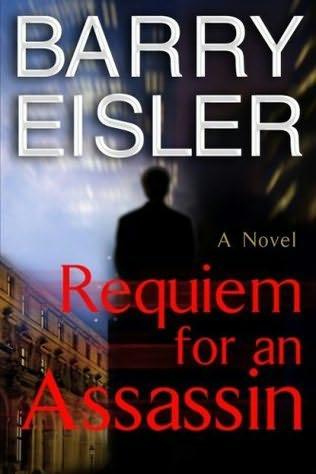

Requiem for an Assassin

maybe one day.

Getting dressed to go out in Bali didn’t usually mean much—this morning, just shorts, a tee-shirt, and sandals. He would have preferred to accessorize with a baby Glock or one of the other pistols he kept handy, but you always had to weigh accessibility, concealability, the likelihood of need, and the likelihood of getting busted for violating Indonesia’s draconian gun laws. This morning, he felt the balance was against the Glock. But that didn’t mean he would be unarmed: he put a Spyderco Clipit Civilian in his front right pocket and hung a Fred Perrin La Griffe with a two-inch spear-point blade around his neck inside the shirt. He grabbed the big backpack he used for groceries, opened the garage, and took out his motorcycle, a 250cc wine-colored Honda Rebel, beat-up, dirty, and reliable as hell.

It was still morning but it was already getting hot, and the air was plenty sticky. He stood there for a moment, just appreciating the feeling of another day in paradise. He liked everything about it, the smell of the mud, even of the duck excrement that fertilized the paddies. It didn’t smell like shit to him at all, it smelled like life, real life far away from all the places covered in concrete and asphalt and choking on diesel. It smelled like the earth itself.

He pulled on his helmet, hating the thing as always because of the heat. The locals didn’t always adhere to Indonesia’s helmet ordinances, but as an obvious foreigner he found it best to do what he could to avoid standing out, especially when standing out meant disrespecting the host country’s laws.

There was no driveway as such; just a quarter-mile-long dirt road. He fired up the bike and motored slowly forward, looking around automatically as he moved, noting the hot spots, checking to see if anything seemed out of order, if anything rubbed him the wrong way. There was no good way to get to him at the villa, which was half the point of its location and design, but the least worst place for an ambush would be somewhere along this road, and so he was always extra alert coming and going here. But nothing was at all amiss this morning, just the usual dogs barking agreeably in the background, the usual farmers sweating at their labors amid the thigh-high rice.

He turned right at the end of the road and picked up speed. A 250cc bike was small for a guy his size, but it’s what everyone around here used and the roads were too narrow and winding to go very fast anyway.

He pulled into the parking lot of the Bintang supermarket on Jalan Raya Ubud and killed the engine. The Bintang was in a two-story stone building with a wood-and-red-tile roof, surrounded by ferns and bamboo trees. It was by far the biggest market in town, and the one Dox liked when he needed more than just a few supplies. Out front were the usual complement of motorbikes, bicycles, and cars. A small dog, one of the scores that roamed Ubud unsupervised, lay in the shade under the front awning, conserving its energy in the gathering tropical heat.

Inside the store, a couple of mothers with diapered toddlers in tow prowled the cramped aisles, shopping for tonight’s dinner, a few household supplies, maybe a bit of candy to keep the baby smiling. Dox had nowhere special to go, and spent a leisurely half-hour moving methodically through the store and loading up a small cart. When he was done, he rolled up to the register, where a pretty girl he knew as Wan was working.

“How are you today, Mr. Dox?” the girl asked him with a beautiful Bali smile.

Dox smiled back, but kept a little distance in his expression. Wan was a tasty-looking little treat, no question, but a sensible man knew not to shit where he ate. Or in this case, shopped. Besides, he could get all he wanted and more an hour away, in Kuta and Sanur.

“Fine, Wan, and how about you? Putting up okay with the heat?”

The girl laughed, her eyes sparkling. “Oh, Mr. Dox, this isn’t hot today, you know that.”

He made a show of mopping his brow. “Darlin’, you’re tougher than I am.”

The groceries cost him a whopping four hundred thousand rupiah—about forty bucks. He wondered if anyone had ever done a study on the prospects of countries where buying groceries cost half a million of the local unit of currency. He doubted there was much correlation between economic health and all those zeros.

He loaded the groceries into his backpack, shouldered it, said goodbye to Wan, and headed outside.

A

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher