![Right to Die]()

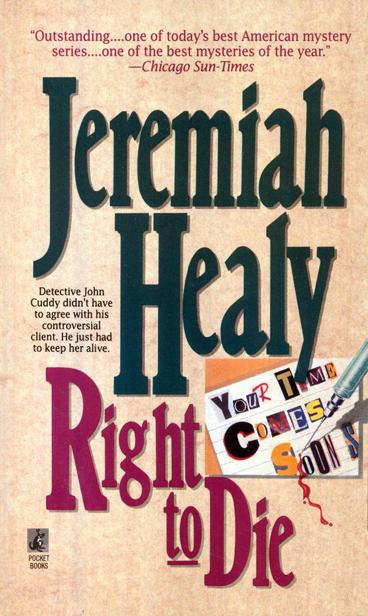

Right to Die

applauding stoically.

An oompah band1 had fun in a supermarket lot. A country and western group strummed from a truck dealership. Under a carport, a souped-up Dodge Charger idled, trunk lid up and facing the street, two stereo speakers booming out the theme from Chariots of Fire.

A younger woman running my pace paired up with me, and we talked in brief, grunted sentences. At one point we had to veer around a video crew in street clothes, gamely jogging beside a TV reporter who was doing her first marathon and providing the station with a “running” commentary.

There were other funny things early in the race, so many I missed a few of the mile markers as I got caught up in the atmosphere. A guy in a Viking helmet. Two women in tuxedos and top hats. A brawny gray-head in a strappy undershirt wearing a coat-hanger crown, the hook dangling an empty Budweiser can a foot in front of his mouth.

And the T-shirts. Every conceivable college and university, but also some with legends, les miserables. say no to drugs. not till you cry, train till you die.

One man’s front read celibate since Christmas, the back, watch the kick .

By mile ten, however, the initial adrenaline was gone. Age ache returned to my knees and hips, and my side at the wound began to burn every other step. I found I had to concentrate. Breathe rhythmically. Maintain the stride. Drink lots of liquids. I also found I had to come to a stop to take the water, otherwise I knocked the cup from the offerer’s hand and couldn’t swallow properly.

My partner pulled up lame at mile eleven. I said I’d wait for her, but dejectedly she said no, it had happened before and wouldn’t get better.

After that the images are a little hazy, just kind of strung together.

Passing Boston ’s Mayor Flynn, a former basketball star at Providence College a couple of academic generations before I hit Holy Cross. I thought back to the tree-lighting ceremony and his short speech, when Nancy almost said the “O” word. Then I looked at Flynn. Hizzoner’s face was red as a beet but the legs still churned, what looked like two well-conditioned cops on either side of him. If he could do it, so could I.

The rain perfect for what we were doing, neither too hot nor too cold. My clothing felt like just a particularly moist outer layer of skin.

A blind man and a sighted woman, him jogging her pace, his hand resting lightly on her forearm. Each smiled a lot, but for each other, not the crowd.

The sweet but refreshing tang of Exceed, the orange drink restoring lost chemicals. Just as Bo said it would.

Runners with numbers at the side of the road in agony, clasping blown-out knees or torn Achilles tendons. Members of the crowd put sacrificed jackets around the runners’ shoulders as race officials with walkie-talkies tried to raise the sweep bus.

Wellesley College , roughly the midpoint of the race. The young women stood four deep, cheering so wildly I heard them for half a mile before the crest of their hill. Some offered liquids, others paper towels to wipe off the salt caking our legs.

On the downslope, passing a woman in her forties. Cellulite jiggled over the backs of her thighs as she muttered her way through a downpour.

Mile fifteen. The legs no worse, but my left side really throbbing now, no matter which foot was striking the ground. I probed it once with my index finger. Just a little blood seeping through the dressing.

Orange rinds, scattered over the road like autumn leaves, slippery as banana peels. After nearly going down once, I began picking my way around them.

Johnny A. Kelley, eighty years young, exulting in his fifty-seventh marathon. A painter’s hat worn backward on his head, he blew kisses to the increased roar he received as each section of the crowd recognized him.

Mile seventeen. Column right onto Commonwealth at the firehouse to begin Heartbreak Hill. Counting the inclines and plateaus to stay oriented, I remembered Bo’s advice and kept my eyes on the horizon. Four-fifths of the field were walking, the other twenty percent of us still running, my knees feeling like I was climbing a rope ladder.

Gaining on a father propelling his son in a wheelchair. I realized the man got no rest at all, having to push on the upslopes and then drag on the downslopes. A few of us offered to spell him. The father smiled and shook a drenched head.

Mile twenty-one. Boston College and the top of Heartbreak. Exhilaration, then the incredible bunching pain in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher