![Saving Elijah]()

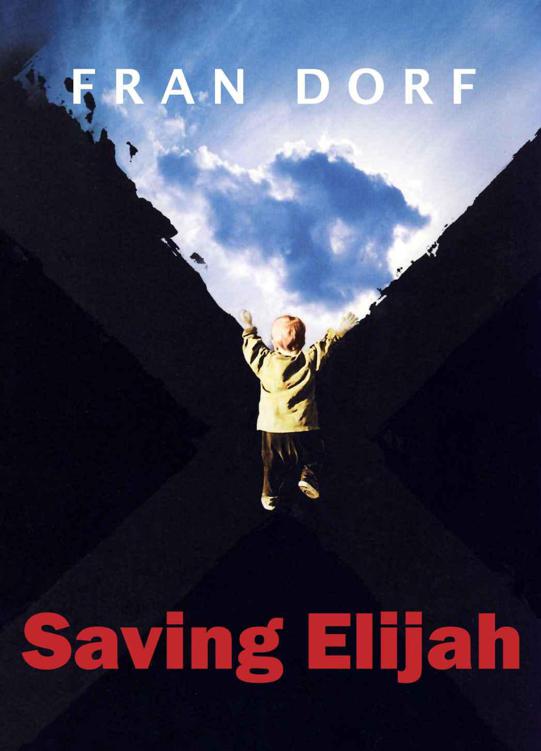

Saving Elijah

walk the Coney Island boardwalk in his underwear. They weren't all as good as Carl, but they all tried the assignments. Except Ellen, who just kept saying, "No, no, I just like to sit and listen." Except that she could hardly hear.

"Well, goodbye then." She waved. Her fingers were as bent as winter twigs, the skin on her fingertips puckered, like dried parchment.

"See you Thursday, Mrs. Shoenfeld." I watched her walk away, then glanced at my watch. It was after two. "I have to go pick up Elijah," I said to Becky. "I promised I'd help set up for the Winter Fair tomorrow."

"What'd they rope you into this year?"

"Elijah and I are in charge of the clown toss." When Brian and Elijah were two, Becky and I took them to a local fair. Brian thought the clown wandering around was funny, but Elijah started screaming at the top of his lungs. I had to take him home. “

"He's come a long way," Becky said. She planted a kiss on my cheek, then we said goodbye and I headed over to the school.

* * *

Most of the children in the class had already been picked up, and Miss Stanakowski was sitting on a floor mat, reading a story to little Isabelle, who had Down syndrome and wore a perpetual smile. Elijah was sitting in the corner next to the piano, by himself. He was tapping a plastic truck on the floor, over and over and over again. His play sometimes mimicked autistic behavior, but he wasn't autistic. There didn't seem to be a formal name for his odd collection of problems, except that he had a non-specific, pervasive developmental disorder.

"Hi, sweetie!"

His face lit. He vaulted to his feet, glasses flashing in the sunlight streaming the large windows. He ran right to me and gave me one of his hugs. Since he didn't have much language at his command, he put his all into a hug, or a dance, or a jump, or any kind of physical movement. His arms were incredibly muscular for a five-year-old, his body was more Schwarzenegger brawny than Galligan lean. When he hugged you, you knew you'd been hugged.

"You know what Elijah did today?" Miss Stanakowski was pregnant. She clapped her hands together. "Go on, Elijah. Show Mom your picture." She always seemed as happy at her students' accomplishments as I'm sure she would have been at her own child's.

Smiling big, Elijah went over to the table where Tuddy and his coat were, and held up his picture. It was actually a cutout of a magazine photo of a horse that he'd pasted on, around which he'd made a few squiggly lines, under which he'd scrawled out the letter E.

"That's beautiful, Elijah," I said, and kissed him.

"He sat through all of circle time," Miss Stanakowski said. "And he counted to twenty. Well, almost. All in all, we had a very good day."

* * *

Kate was already home when we got there. Right before my eyes, right under my nose, my daughter is turning into a beauty. Pale, glowing skin, shining auburn hair, luminous dark eyes, the lush fifteen-year-old figure with which each of us is gifted only once in our lives, even those of us who were chubby.

Of late she'd taken to reading books by the feminists of my own era, and confessional women poets such as Sexton, Plath, and Sharon Olds; loudly declaring her independence from men; and wearing ragged jeans and baggy shirts, as protest against the ridiculous lengths women go to for their looks. Her sabotage was unsuccessful at hiding her beauty. Still, Charlotte, wearing Calvin Klein, sniffed, "Kate, honey, I know a nice hobo I could introduce you to." My throat tightened and I started to tell her to leave my daughter alone. But Kate had her own comeback: "Actually, Grandma Charlotte, I'm holding out for a Calvin Klein bum. Heroin chic, you know?" Charlotte actually giggled. Would wonders never cease?

Now Kate was in the kitchen, peering into the refrigerator. Poppy was sitting on his haunches beside her, hoping she was in a sharing mood. Any little morsel would do.

The Galligan family dog is species canine, mix unknown. Body as big as a shepherd, legs as short as a basset hound, brain the size of a pea. We named him Poppy when we first brought him home from the shelter. Elijah, who had a vocabulary of about six words, kept pointing to him and saying "puppy." I suggested we call him Puppy, but his older brother thought that was a dumb name for a dog. "How about Poppy?" Alex said. Even dumber, but it stuck.

Kate glanced over her shoulder at me. "Mom, why don't we ever have anything to eat in this house?" I'd

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher