![Saving Elijah]()

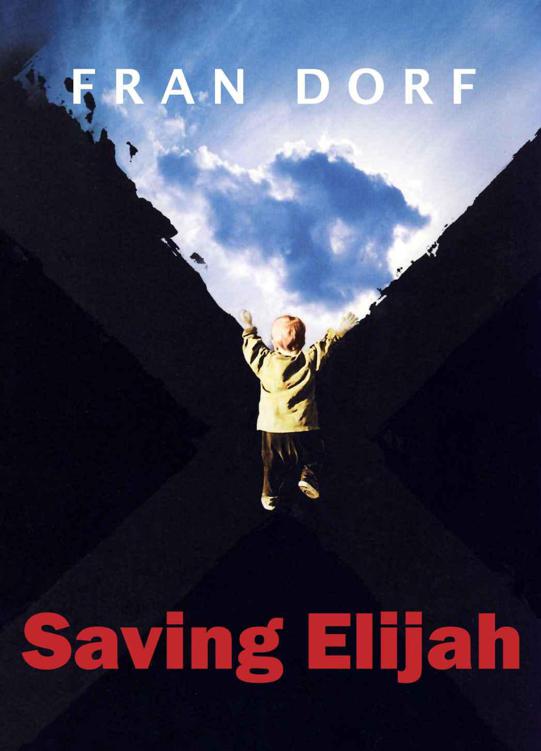

Saving Elijah

disaster straight on.

I watched her press her lips to Elijah's forehead, careful not to disturb the tube in his nose or the one in his throat. She stayed that way for a moment, lips pressed to his skin, eyes closed. I saw her whisper his name, an act of simple kindness that moved me from numbness to tears. When she stood up she had tears in her eyes, too.

"I need some air," Sam said then. "I'm going for a walk." He glanced at me as he stood up, perhaps expecting a reaction.

That morning I think I must have given him a horrified look when he said he was going for a run. "I've got to get my blood pumping," he said. "Be back soon." And he was gone. Sam has always been a jock, but I had slipped into some other universe where normal routines didn't exist. Why hadn't he? Now I watched him leaving the room again and wondered how he could move so quickly when I seemed to be doing everything in slow motion, like an old LP record grinding down. Had he even noticed that Becky's husband, Mark, the other half of our so-called best friends, had yet to make the one-hour trip?

The ghost was out there singing again, I could hear it above the din of the PICU. I tried not to listen but there was no way to shut my ears.

All night long their nets they threw

To the stars in the twinkling foam.

Then down from the skies came the wooden shoe,

Bringing the fishermen home.

Sam would be walking through the corridor, right now.

"Do you hear that, Becky?" Do (breath) you (breath) hear (breath) that?

"Hear what?"

"I sing that lullaby to Elijah. Every night. Listen."

She peered through the glass wall of the NAR, as if to search for a musician playing a song she clearly didn't hear. "What lullaby?"

" 'Wynken, Blynken, and Nod.'" How could I not have told her how Elijah had to have that lullaby and no other before he would go to sleep? It was so very important. All the time we'd wasted on memories, gossip, complaints about our parents and our husbands, exchanges of information about our children and the difficulties of raising them, reports of minor flirtations (one major, in Becky's case), and I'd left the lullaby out.

"I don't hear anything, Dinah."

Obviously no one could see the ghost except me. Nor could they hear his song. Maybe I was imagining the whole thing.

Becky sat down in the empty chair next to me, leaned forward, and stretched out her arms. I couldn't bear it. I was having so much trouble breathing. Just the thought of someone hugging me, touching me, putting pressure on my body—even my friend, even my husband—made me gag. It would cut off my already diminished air supply.

I knew I was shocky. The panic and breathlessness and sleeplessness were unmistakable symptoms. I'd certainly treated enough bereaved parents in my fifteen years of practice to know at least some of the details of Big Time Grief. My own grandmother had lost a child, one of my mother's brothers. He was only four at the time; my grandmother never got over it. It's interesting there's no name for it, for a sonless or daughterless mother, like widow, or orphan.

But was it a blessing or a curse to know I was in shock and even to know some of what I would face if Elijah didn't survive? Did it help or hurt me to know that if my son died I would never get over it, that it would sit like a monster on my head for the rest of my life? That there would be some people I had thought friends who would abandon me?

"I can't." I pulled away from her.

"It's okay, Dinah." She folded her perfectly manicured hands on her lap. "I spoke to Addie this morning. She said she came yesterday."

Addie, another friend, an artist who designs book jackets for a publishing company in New York. When Elijah was born she gave him a small chest she'd hand-painted with white and blue polka-dot dinosaurs.

I nodded, looked down at my trembling hands. I couldn't bring myself to care if my friends came, or if they didn't come. Their coming didn't change anything. Either way I hurt more than I had ever believed possible. If Elijah didn't survive, I would never be able to forgive them for not coming, would never again consider them my friends no matter what their reasons: didn't know what to say, too busy, too far away, too uncomfortable, too scary, too whatever.

"Mark sends his love and prayers," Becky said.

I nodded as enthusiastically as I could. A barely perceptible nod. Where was Mark, anyway? Was he going to be one of the abandoners?

"Is there anything I can do for you, Dinah?"

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher