![Saving Elijah]()

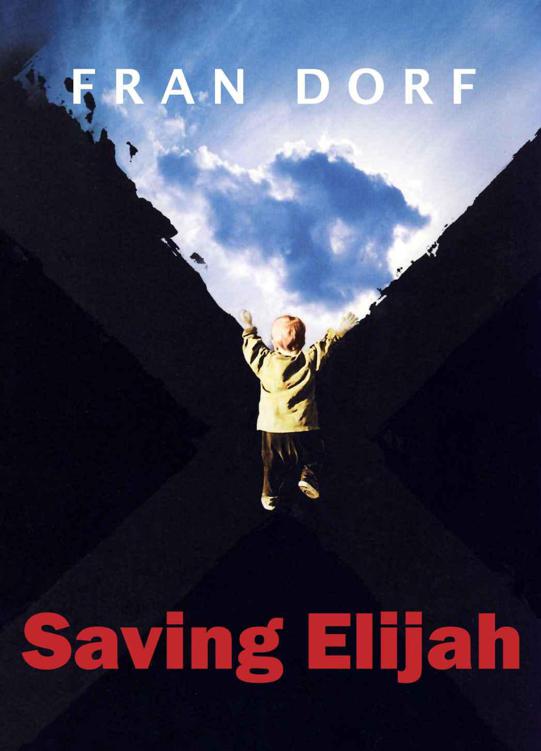

Saving Elijah

think Sam would turn to you for strength. And you'd turn to him. But Elijah isn't going to die." She came back over to the bed and squeezed his limp hand. "Isn't that right, Elijah?"

Elijah slept on, his breathing machine whoosh-pumping away.

Becky was wrong about Sam and me. You'd think couples would cleave to each other, but they don't. Most don't, anyway. My patient Laura Soffel and her husband couldn't talk to each other about their dead son Tom and eventually divorced because they couldn't talk about anything else, either. Sheila Morrison and her husband talked all the time, Sheila to me, her therapist, the two of them to their parish priest, fellow grief support group members, to a psychic, and finally to a divorce lawyer. And Grandma Elizabeth and Grandpa Eli? My mother didn't speak to them for years and I met them only them eight or nine times, but during those few visits I was witness to my grandparents' bitter battleground of mutual blame.

Sam and Dinah would be no different. What always seemed to melt and mix and mesh perfectly with Sam and me, in exactly the right proportions and measures, in a marriage that tasted sweet and happy, would burst and split apart like a piece of fruit dropped from a great height. I didn't know the words we would use to hurt each other, the blame we would hurl at each other. But I knew that our equation, Sam's and mine, our formula, the ratios that defined our marriage, would no longer apply, do not apply once you lose a child.

I could not imagine Sam without Elijah. And how would I survive if every molecule in my body had been corrupted? I'm not sure when the molecule thing happens, as you carry a child or simply as you mother him, but I was sure that each of my cell nuclei was unalterably made up of four parts, one part me, one part Kate, one part Alex, and one part Elijah. If a crucial Elijah-piece of each cell nucleus were suddenly sliced off at the cellular level, I was certain the missing piece of each cell would defile the whole structure until, eventually, it crumbled to dust. I could feel edges crumbling already.

My patients who'd lost children had certainly been more functional when they left me than when they came to me. Functional? Was that the salient word? Now, in the hospital room, I realized that nobody anywhere, no therapist, certainly, possessed a diagnostic guide for this, no DMRDMC (first edition): Diagnostic Manual for Rebuilding Destroyed Mother Cells.

"What does the doctor say?" Becky asked.

"That he's going to wake up soon."

Becky nodded, sat silently for a while again. Then, "Can I get you anything else?"

Could she get me back to before this? Could she trade places with me, could it be Brian lying here like this and not Elijah? No. Wait. I didn't mean that.

I no longer felt like a real human being. I belonged out in the corridor with a ghost.

Sam came back then. He looked so very tired, weary and bleary-eyed. Other than that, he didn't look much different than the first time I met him, while waiting to register for my freshman courses at George Washington University. I was shuffling through my papers to make sure I had everything I needed and dropped my yellow card, the one you had to show to the registrar. It landed right at Sammy's feet.

"That's mine," I said, reaching for it at the same time he did, thinking what a cute guy he was. Gentle brown eyes, tall and lanky, dark tousled hair, wire-rimmed glasses, worn flannel shirt, unbuttoned sleeves. A killer smile, complete with dimples.

"You don't want to forget this." He handed the card back to me. "No money, no tickie."

A boy wearing a Hendrix T-shirt, fatigue pants, and a rawhide headband tapped Sam's shoulder. "Hey, man, it's your turn."

"Hey, man," Sam said with an easy smile at me, "give me a break, I'm talking to a pretty girl here."

Now, in the hospital, Sam sat down, radiating frigid air, smelling of grease, probably stopped in the hospital cafeteria for a bite. "It's cold outside."

"They're saying snow," Becky said.

Right. It was winter. Elijah loved snow. I wanted to tell him it was snowing, whisper it in his ear, shout it in his face, but I didn't want them to see me do this. I would wait until I was alone with him. And then I would tell him and tell him and he'd wake up so that we could go out and play in the snow.

I closed my eyes, again, and, once again the sights and smells of a hospital room vanished and I was transported somewhere else, to another time and place.

*

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher