![Saving Elijah]()

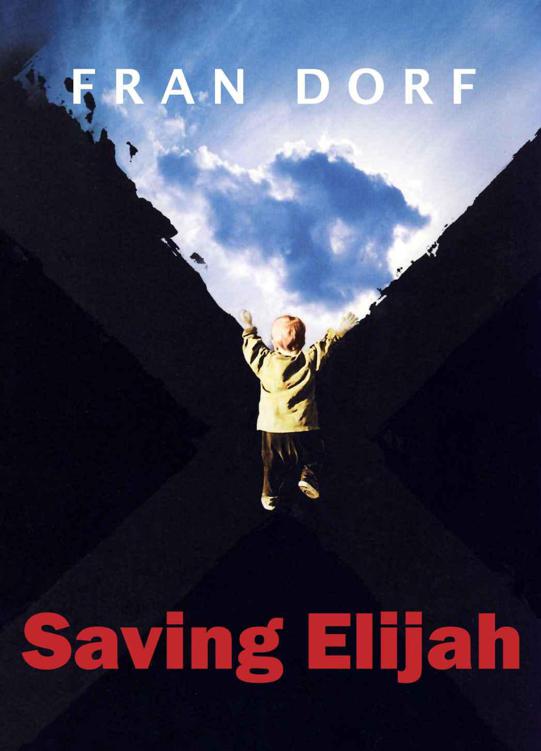

Saving Elijah

Becky said finally. "Do you want something to eat? It's just about dinnertime."

"I'm not hungry."

"How about at the house? Bring dinner for the kids tomorrow?"

"Sam's parents are staying with them," I said. "Bringing them down in the evenings."

Becky nodded. "Is there anything I can do for you, Di?"

I was listening to the ghost's music. But I'm smart. I wasn't going to ask for corroboration again.

"Could you call the Jewish Community Center, tell them I won't be teaching the class for a while?"

"They know, Dinah. Sam must have called. And I saw Mrs. Shoenfeld there the other day, when I took Brian to his swimming class."

Was it only a few days ago that Becky and I saw her on the street? No. It was a week. More than a week.

"I was amazed she recognized me," Becky said.

I wasn't.

"She asked me how you were doing, seemed very concerned about Elijah." Becky glanced at him. "Has she met him?"

"Once." Last summer I'd registered Elijah for Krafty Kids, an art class given at the same time I give my writing class. I'd talked to the teacher about his learning disabilities, and told her the day I brought him in that I'd be right down the hall if there was a problem. There was. Elijah tried to finger-paint one of the other kids, and the teacher brought him to me long before the hour was up. "I told him he couldn't do that," she said, "and he's been sitting in a corner and crying ever since. I'm sorry. It's too much of a disruption." She nudged him toward me, then left.

I introduced him to my class. Even though he went off into a corner and banged a pair of little plastic cars on the floor instead of standing there with me and letting them engage him the way most children would have, they fussed and fawned over him. That made me feel good, of course, and Ellen Shoenfeld was one of the fussers and fawners. But only she acknowledged the obvious, that Elijah was not a normal child. "It must be hard for you, Dinah."

"She asked me if it'd be all right if she wrote you a note," Becky said. "I told her I thought it would."

I felt oddly moved by this. Ellen is a Holocaust survivor. Nobody had told me, but she's eighty and Jewish and speaks with a fairly heavy German accent, which means she probably immigrated later in life, which means circumstances probably found her in Germany when Hitler came to power. Clearly she doesn't talk about it openly, as some survivors do, and when I asked the question all she said was, "Yes, I was there when it happened." Then she walked away.

"She said you're a wonderful woman," Becky said.

"Don't know why she thinks so. She's shown up at every class this session, but so far hasn't written a thing."

"Why would she come but not write?"

"I don't know."

Becky smiled. "You love that class, don't you?"

My eyes were filling with tears, my breath quickening with another wave of panic. Ordinary conversation felt like a runaway train. "I can't talk about the class now, Beck."

"I'm sorry. Look, I'm going to get a sandwich for you—you don't have to eat it, you can just put it on the table and then you'll have it if you want it."

She left. I couldn't possibly eat anything, but I'm sure she was relieved to have a mission. Perhaps she'd come back telling tales of ghosts sitting in corridors, playing guitars.

I rested my head again on the bed next to Elijah's belly and closed my eyes. Even so, I could see six parallel lines on the monitors beneath my eyelids, inching their way across the two screens over and over. Pulse rate, blood pressure, pulse oxygen, expiratory pressure, respiratory pressure, and ventilator rate burnished into my brain. When Becky got back I was still watching lines, listening to the whoosh-suck click-pump, and hearing a song of beautiful dreams and fishermen three.

"I got you roast beef on rye, is that okay? And a soda. At least take a drink." She put the provisions on the table next to the bed and sat down. "I didn't see Sam downstairs," she said. "He must still be outside walking."

I nodded. "What do you think he'll do if Elijah dies?"

Becky flinched. "Dinah! Elijah is not going to die."

"But if he does?"

"I don't think you should talk that way in front of him. Maybe he can hear you."

And maybe he'd hear me talking that way about him and get mad and open his eyes.

"He's my son, I'll talk any way I want to."

She sighed, stood up, and walked over to the glass window, looked out into the PICU for a moment, then turned around. "I think you'd both be devastated. I

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher