![Shame]()

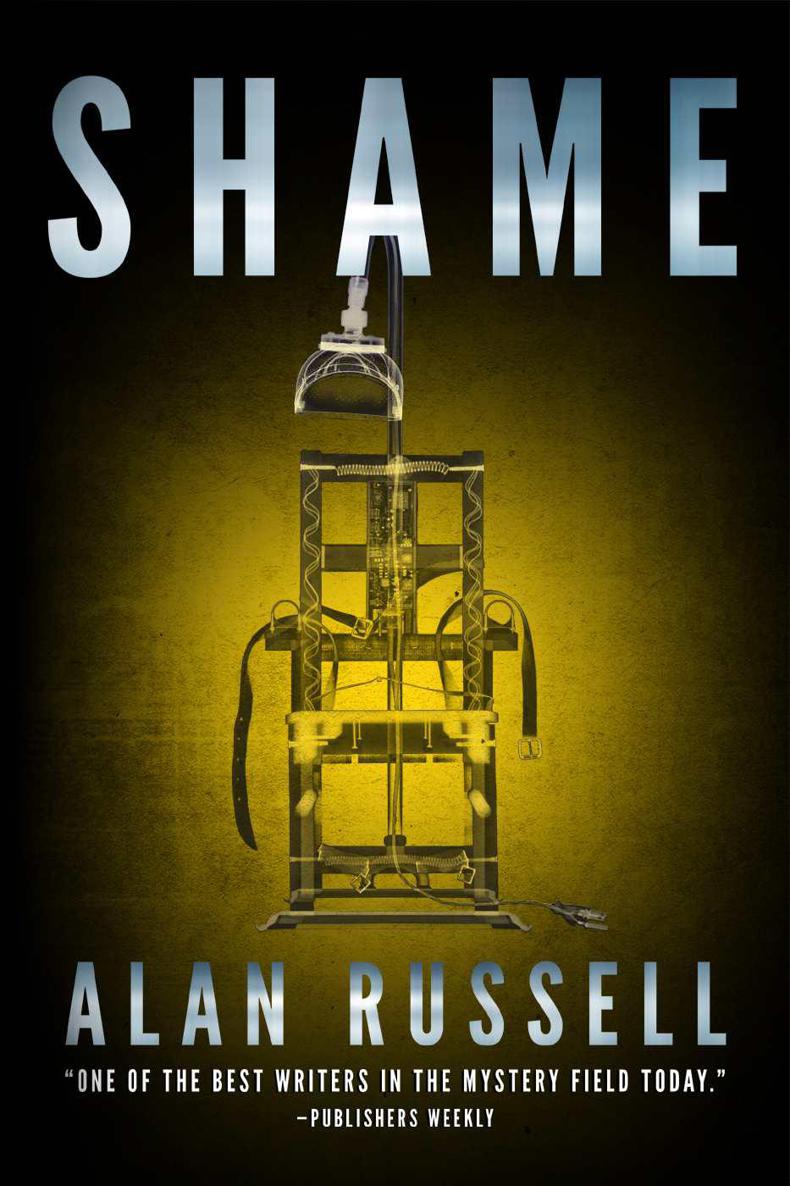

Shame

hard to hide.”

They both contemplated that. And then Caleb remembered something about her book that had bothered him, a section he’d found cryptic, different from the rest.

“It’s probably not my place to ask, but...”

“Yes?”

“I was curious about my father’s death. Your book was personal in so many ways, and yet when it came to describing his execution your writing was very...”

Elizabeth found the word for him: “Mechanical.”

“Yes.”

She had her pat answers; that the book was about the living Gray Parker; that death speaks for itself; that she hadn’t wanted to be a ghoul; but those were lies.

“I have to make an admission: I had a great deal of trouble writing about your father’s death. That’s something no one knows except my editor.”

Elizabeth continued haltingly. “Your father all but asked the world to do away with him. He was the one who called up the police and said, ‘Here I am.’ And he was the one who streamlined the legal process to expedite his death, doing his best to handcuff his own defense lawyers. At the same time, though, he had what I would have to call a love of life. Ironic, isn’t it, that he could kill so callously and yet love life. And so I kept trying to dig for answers. In the end, it was hard digging.”

“I see.”

Elizabeth shook her head, frustrated with herself and her answer. I’m lying again, she thought. She expected Caleb to be honest with her, and yet she wasn’t willing to reciprocate. Shame syndrome. They were both expert at avoiding their pasts.

“That’s not really it, though,” she said. “I tried writing about his death as I experienced it, but it tore at me too much. I tried and tried and tried. And what I finally did write my editor didn’t like. She said it wouldn’t play in Peoria.”

“What wouldn’t?”

“My thoughts on his death. She said they were too sympathetic. She reminded me over and over that this was a man virtually everyone wanted to see dead. Final justice was what the country wanted, both in person and in print. She told me my observations were

disjointed and emotional

. I remember howharsh those words seemed. She said my objectivity was lacking. But what she objected to most was the elephant.”

“The elephant?”

“The elephant that kept trumpeting in my head. Not an angel of death, but an elephant. I wrote how in your father’s final hours on this earth I kept imagining this elephant’s agonized cries as I watched everyone getting ready to kill him. My editor thought it read like Sylvia Plath meets James Joyce, when what it should have been was Truman Capote meets Norman Mailer.”

Elizabeth shivered and was glad Caleb wasn’t there to see that.

“Your father invited me to watch him die. That’s not the kind of invitation you get every day. I was ambivalent about going, but my publisher insisted.

“I arrived early and spent that time walking outside the prison, nerving myself up before going inside. Around me it felt as if a pep rally were going on, not a death watch. I made my way through the crowd. Most who were there were young, loud, and drunk. There were vendors selling buttons, T-shirts, and Shame voodoo dolls. There was even a disc jockey broadcasting live. Every hour on the hour he threw eggs and bacon on a hot pan and then played the sizzling sounds over loudspeakers. That was always good for deafening cheers. The countdown to death was like waiting for the ball to drop on New Year’s Eve. But the music, the crowds, even the cheers were just background noise to me. What I kept hearing was that elephant trumpeting.

“I know the reason for it. There’s a logical explanation. There always is. While researching capital punishment I discovered that Thomas Edison was one of those who had worked on building a better fatal mousetrap.”

“Edison?”

“It surprised me, too. I always thought of Edison as this dedicated scientist who tirelessly worked for the sake of scientificinquiry. I remember in school I had this teacher who always used to quote Edison to motivate us. I can still hear her now: ‘Genius is ninety-nine percent perspiration, and one percent inspiration.’ But I learned about Edison’s strange sideline show. He paid the children around his Menlo Park neighborhood a quarter each for every stray dog and cat they could round up. Thirty pieces would have been more appropriate. Those were animals earmarked for death. They were paraded about in much-publicized

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher