![Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)]()

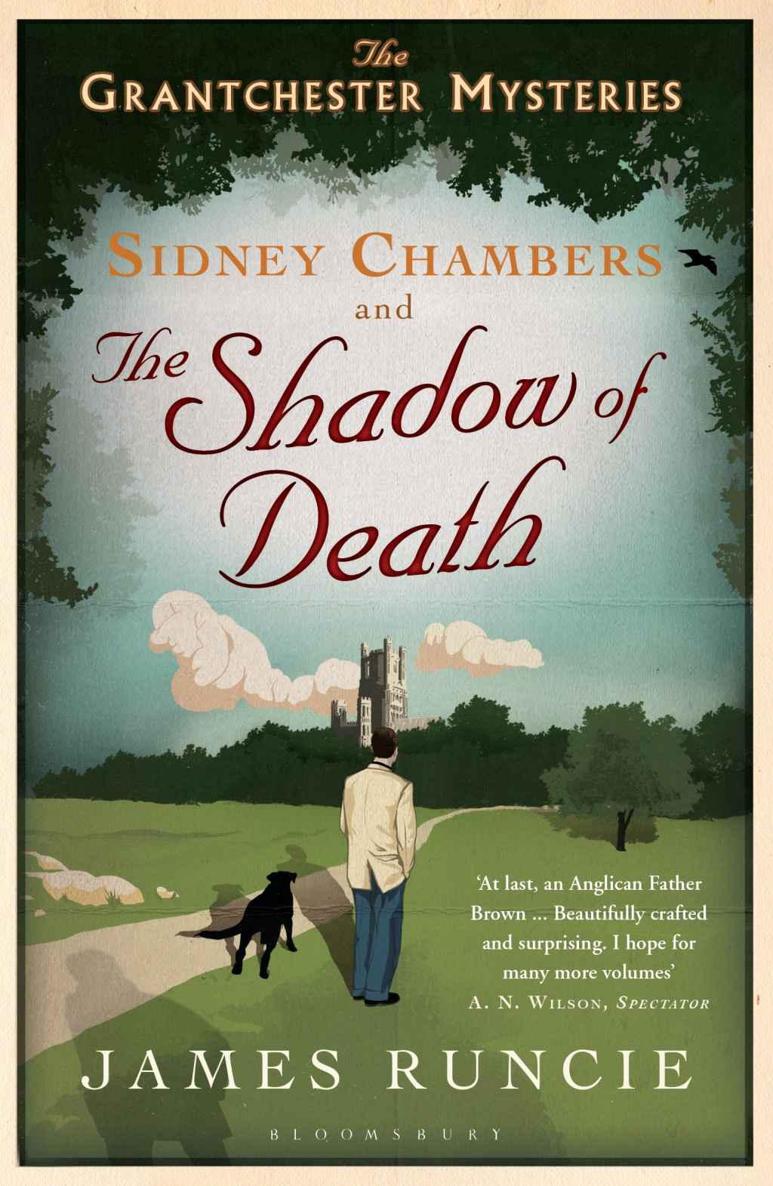

Sidney Chambers and The Shadow of Death (The Grantchester Mysteries)

Morton continued.

‘You think so?’

‘Don’t get me wrong,’ Clive Morton continued. ‘I liked the man. We used to be close but, as I’ve implied, he had become much more distant of late: remote and moody to boot. And you can’t work with a partner who is half-cut after lunch.’

‘I wonder if Miss Morrison may have had to cover up for him?’

‘Well spotted, Canon Chambers. It was getting ridiculous. I told Stephen I was prepared to turn a blind eye in the evenings but you can’t employ a man who can get drunk twice in a day.’

‘It was as bad as that?’

‘Sometimes. I’m not saying he was an alcoholic. It’s that his mind wasn’t on the case in hand. I had to warn him, of course.’

‘That he might lose his job?’

‘Yes. Even though we were partners something had to be done.’

‘And he knew this?’

‘Of course he knew it. I was the one that told him.’

‘And do you think the idea of losing everything might have made him despair?’

‘I am not going to feel responsible for Stephen’s death if that is what you are getting at, Canon Chambers. He had plenty of opportunities to sort his life out. I won’t pretend it was easy but I always dealt with him fairly – no matter how many times he went to London or disappeared without telling anyone. At least Miss Morrison kept tabs on him. She could always be relied upon to finish off the paperwork and let us know where he was in the event of an emergency. He didn’t seem to have any problems with her. It was the rest of the business that suffered from his rather cavalier approach. But, if you’ll excuse me, it’s my golfing afternoon.’

‘Golf?’

‘Every Wednesday. It helps to break up the week. I sometimes combine it with business. So much easier when you are out of the office . . .’

‘And were you playing golf the afternoon that your colleague died?’

‘Afternoon? He died after work, didn’t he? We always shut up shop early on a Wednesday. That’s how Stephen made sure he couldn’t be stopped. It’s a terrible business. When a man decides to do something so drastic there’s nothing you can do to stop him, don’t you think?’

‘I suppose not,’ Sidney replied. ‘And there were no big arguments with clients, that sort of thing? No one who might have a grievance against him?’

‘None, as far as I am aware. Solicitors can sometimes get on to the wrong end of things but I was always confident that Stephen could charm his way out of a tricky situation. What are you getting at?’

Sidney paused. ‘It’s nothing, I’m sure,’ he replied. ‘I am sorry to have taken up so much of your time.’

‘That’s quite all right. I don’t mean to rush you but I don’t think we were expecting you. We don’t have much call for clergymen in the office . . .’

‘And I admit that, in the church, we don’t have much call for lawyers . . .’ Sidney replied, more testily than he had intended.

He had never taken such dislike to a man before and immediately felt guilty about it. He remembered his old tutor at theological college telling him, ‘There is something in each of us that cannot be naturally loved. We need to remember this about ourselves when we think of others.’

On the way out of the office, Sidney felt ashamed of his rudeness. He worried about the kind of man he was becoming. He needed to return to his official duties.

He bicycled over to Corpus and arrived just in time to take his first seminar of the term. It was on the synoptic gospels, a study of how much the life of Christ found in the accounts of Matthew, Mark and Luke was dependent on a common, earlier source known as ‘Q’.

Sidney was determined to make his teaching relevant. He explained how, although ‘Q’ was lost, and the earliest surviving gospel accounts could only have been written some sixty-five years after the death of Christ, this was not necessarily such a long passage of time. It would be the equivalent of his students writing an account of their great-grandfather just before the turn of the century. By gathering the evidence, and questioning those who had known him, it would be perfectly possible to acquire a realistic account of the life of a man they had never met. All it needed was a close examination of the facts.

Sidney spoke in familiar terms because he had discovered that when students were first at Cambridge they required encouragement as much as academic tuition. On arrival, those who had been brilliant at

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher