![Strange Highways]()

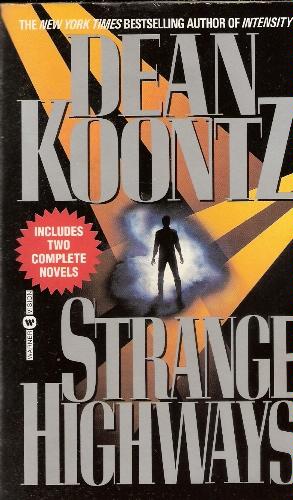

Strange Highways

three-way intersection, directly across from the entrance to Coal Valley Road. He switched off the headlights but left the engine running.

Overhung by autumnal trees, those two lanes of wet blacktop led out of the deepening twilight and vanished into shadows as black as the oncoming night. The pavement was littered with colorful leaves that glowed strangely in the gloom, as though irradiated.

His heart pounded, pounded.

He closed his eyes and listened to the rain.

When at last he opened his eyes, he half expected that Coal Valley Road wouldn't be there any more, that it had been just one more hallucination. But it hadn't vanished. The two lanes of blacktop glistened with silver rain. Scarlet and amber leaves glimmered like a scattering of jewels meant to lure him into the tunnel of trees and into the deeper darkness beyond.

Impossible.

But there it was.

Twenty-one years ago in Coal Valley, a six-year-old boy named Rudy DeMarco had tumbled into a sinkhole that abruptly opened under him while he was playing in his backyard. Rushing out of the house in response to her son's screams, Mrs. DeMarco had found him in an eight-foot-deep pit, with sulfurous smoke billowing from fissures in the bottom. She scrambled into the hole after him, into heat so intense that she seemed to have descended through the gates of Hell. The floor of the pit resembled a furnace grate; little Rudy's legs were trapped between thick bars of stone, dangling into whatever inferno was obscured by the rising smoke. Choking, dizzy, instantly disoriented, Mrs. DeMarco nevertheless wrenched her child from the gap in which he was wedged. As the unstable floor of the pit quaked and cracked and crumbled under her, she dragged Rudy to the sloped wall, clawed at the hot earth, and frantically struggled upward. The bottom dropped out altogether, the sinkhole rapidly widened, the treacherous slope slid away beneath her, but still she pulled her boy out of the seething smoke and onto the lawn. His clothes were ablaze. She covered him with her body, trying to smother the flames, and her clothes caught on fire. Clutching Rudy against her, she rolled with him in the grass, crying for help, and her screams seemed especially loud because her boy had fallen silent. More than his clothes had burned: Most of his hair was singed away, one side of his face was blistered, and his small body was charred. Three days later, in the Pittsburgh hospital to which he had been taken by air ambulance, Rudy DeMarco died of catastrophic burns.

For sixteen years prior to the boy's death, the people of Coal Valley had lived above a subterranean fire that churned relentlessly through a network of abandoned mines, eating away at untapped veins of anthracite, gradually widening those underground corridors and shafts. While state and federal officials debated whether the hidden conflagration would eventually burn itself out, while they argued about various strategies for extinguishing it, while they squandered fortunes on consultants and interminable hearings, while they strove indefatigably to shift the financial responsibility for the clean-up from one jurisdiction to another, Coal Valley's residents lived with carbon-monoxide monitors to avoid being gassed in the night by mine-fire fumes that seeped, up through the foundations of their homes. Scattered across the town were vent pipes, tapping the tunnels below to release smoke from the fire and perhaps minimize the build-up of toxic gases in nearby houses; one even thrust up from the elementary-school playground.

With the tragic death of little Rudy DeMarco, the politicians and bureaucrats were at last compelled to take action. The federal government purchased the threatened properties, beginning with those houses directly over the most hotly burning tunnels, then those over secondary fires, then those that were still only adjacent to the deep, combustible rivers of coal. During the course of the following year, as homes were condemned and the residents moved away, the reasonably pleasant village of Coal Valley gradually became a ghost town.

By that rainy night in a long-ago October, when Joey had taken the wrong road back to college, only three families remained in Coal Valley. They had been scheduled to move out before Thanksgiving.

In the year that followed the departure of those last residents, bulldozers were to knock down

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher