![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

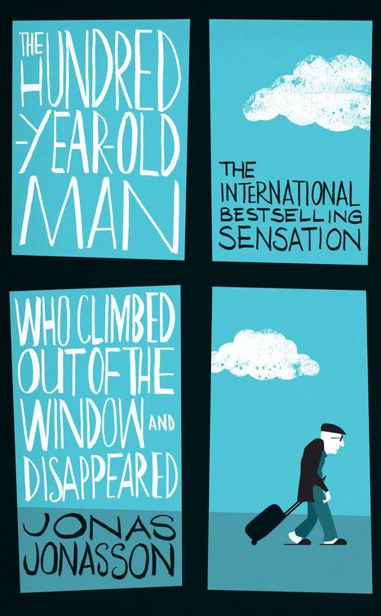

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

be apologising for the fact that there was finally a bit of action in Julius Jonsson’s life.

Julius was back in good form. He thought it was high time that they both had a look at what was in the suitcase. When Allan pointed out that it was locked, Julius told him not to be silly.

‘Since when has a lock stopped Julius Jonsson?’ asked Julius Jonsson.

But there is a time for everything, he went on. First there was the matter of the problem on the floor. It wouldn’t do if the young man were to wake up and then carry on from where he left off when he passed out.

Allan suggested that they tie him to a tree outside the station building, but Julius objected that if the young man shouted loudly enough when he woke up he would be heard down in the village. There were only a handful of families still living there, but all had – with more or less good reason – a bit of a grudge against Julius and they would probably be on the young man’s side if they got the chance.

Julius had a better idea. Off the kitchen was an insulated freezer-room where he stored his poached and butchered elks. For the time being the room contained no elks, and the fan was turned off. Julius didn’t want to use the freezer unnecessarily because it used a hell of a lot of electricity. Julius had of course hot-wired it, and it was Gösta at Forest Cottage farm who unknowingly paid, but it was important to steal electricity in moderation if you wanted to keep taking advantage of the perk for a long time.

Allan inspected the turned-off freezer and found it to be an excellent cell, without any unnecessary amenities. The six by nine feet was perhaps more space than the youth deserved, but there was no need to make conditions unnecessarily harsh.

The old men dragged the young man into the freezer. He groaned when they put him on an upturned wooden chest in one corner and propped his body against the wall. He seemed about to wake up. Best to hurry out and lock the door properly!

No sooner said than done. Upon which Julius lifted the suitcase onto the kitchen table, looked at the lock, licked clean the fork he had just used for the evening’s roast elk with potatoes, and picked the lock in a few seconds. Then he beckoned Allan over for the actual opening, on the grounds that it was Allan’s booty after all.

‘Everything of mine is yours too,’ said Allan. ‘We share and share alike, but if there is a pair of shoes in my size then I bags them.’

Upon which Allan opened the lock.

‘What the hell,’ said Allan.

‘What the hell,’ said Julius.

‘Let me out!’ could be heard from the freezer-room.

Chapter 4

1905–1929

Allan Emmanuel Karlsson was born on 2nd May 1905. The day before, his mother had marched in the May Day procession in Flen and demonstrated on behalf of women’s suffrage, an eight-hour working day and other utopian demands. The demonstrating had at least one positive result: her contractions started and just after midnight her first and only son was born. She gave birth at home with the help of the neighbour’s wife who was not especially talented at midwifery but who had some status in the community because as a nine-year-old she had had the honour of curtsying before King Karl XIV Johan, who in turn was a friend (sort of) of Napoleon Bonaparte. And to be fair to the neighbour’s wife, the child she delivered did indeed reach adulthood, and by a very good margin.

Allan Karlsson’s father was both considerate and angry. He was considerate with his family; he was angry with society in general and with everybody who could be thought of as representing that society. Finer folk disapproved of him, dating back to the time he had stood on the square in Flen and advocated the use of contraceptives. For this offence he was fined ten crowns, and relieved of the need to worry about the topic any further since Allan’s mother out of pure shame decided to ban any further entry to her person. Allan was then six and old enough to ask his mother for a more detailed explanation of why his father’s bed had suddenly been moved into the wood-shed. He was told that he shouldn’t ask so many questions unless he wanted his ears boxed. Since Allan, like all children at all times, did not want his ears boxed, he dropped the subject.

From that day on, Allan’s father appeared less and less frequently in his own home. In the daytime he more or lesscoped with his job on the railways, in the evening he discussed socialism at

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher