![The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared]()

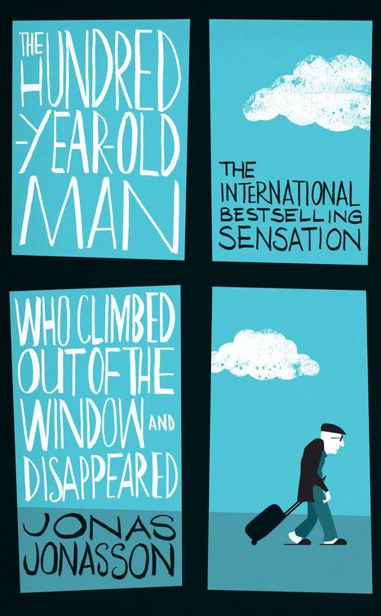

The 100-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out the Window and Disappeared

didn’t really understand what his mother meant. But he understood that his father was dead, that his mother coughed and that the war was over. As for himself, by the age of thirteen he had acquired a particular skill in making explosions by mixing nitroglycerine, cellulose nitrate, ammonium nitrate, sodium nitrate, wood flour, dinitrotoluene and a few other ingredients. That ought to come in handy some day, thought Allan, and went out to help his mother with the wood.

Two years later, Allan’s mother finished coughing, and she entered that imagined heaven where his father was possibly already established. Then, on the threshold of the little house, Allan found an angry Mr Wholesale Merchant who thought that Allan’s mother should have paid her debt of nine crowns before she – without telling anyone – went and died. But Allan had no plans to give Gustavsson anything.

‘That’s something you’ll have to talk to her about yourself, Mr Wholesale Merchant. Do you want to borrow a spade?’

As wholesalers often are, the man was lightly built, compared with the fifteen-year-old Allan. The boy was on his way to becoming a man, and if he was half as crazy as his father then he was capable of anything, was how Mr Wholesale Merchant Gustavsson saw it, and since he wanted to be around quite a bit longer to count his money, the subject of the debt was never raised again.

Young Allan couldn’t understand how his mother had managed to scrape together several hundred crowns in savings. But the money was there anyway, and it was enough to bury her and to start the Karlsson Dynamite Company. The boy was only fifteen years old when his mother died, but Allan had learned all he needed at Nitroglycerine Ltd.

He experimented freely in the gravel pit behind the house; once so freely that two miles away the closest neighbour’s cow had a miscarriage. But Allan never heard about that, because just like Mr Wholesale Merchant Gustavsson, the neighbour was a little bit afraid of crazy Karlsson’s possibly equally crazy boy.

Since his time as an errand boy, Allan had retained his interest in current affairs. At least once a week, he rode his bicycle to the public library in Flen to update himself on the latest news. When he was there he often met young men who were keen to debate and who all had one thing in common: they wantedto tempt Allan into some political movement or other. But Allan’s great interest in world events did not include any interest in trying to change them.

In a political sense, Allan’s childhood had been bewildering. On the one hand, he was from the working class. You could hardly use any other description of a boy who ends his schooling when he is ten to get a job in industry. On the other hand, he respected the memory of his father, and his father during far too short a life had managed to hold views right across the spectrum. He started on the Left, went on to praise Tsar Nicholas II and rounded off his existence with a land dispute with Vladimir Ilyich Lenin.

His mother, in between her coughing fits, had cursed everyone from the King to the Bolsheviks and, in passing, even the leader of the Social Democrats, Mr Wholesale Merchant Gustavsson, and – not least – Allan’s father.

Allan himself was certainly no fool. True, he only spent three years in school, but that was plenty for him to have learned to read, write and count. His politically conscious fellow workers at Nitroglycerine Ltd. had also made him curious about the world.

But what finally formed young Allan’s philosophy of life were his mother’s words when they received the news of his father’s death. It took a while before the message seeped into his soul, but once there, it was there for ever:

Things are what they are, and whatever will be will be.

That meant among other things that you didn’t make a fuss, especially when there was good reason to do so, as for example, when they heard the news about his father’s death. In accordance with family tradition, Allan reacted by chopping wood, although for an unusually long time and particularly quietly. Or when his mother followed his father’s example, and as a result was carried out to the waiting hearse. Allan stayed in thekitchen and followed the spectacle through the window. And then he said so quietly that only he could hear:

‘Well, goodbye, mum.’

And that was the end of that chapter of his life.

Allan worked hard with his dynamite company and during the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher