![The Barker Street Regulars]()

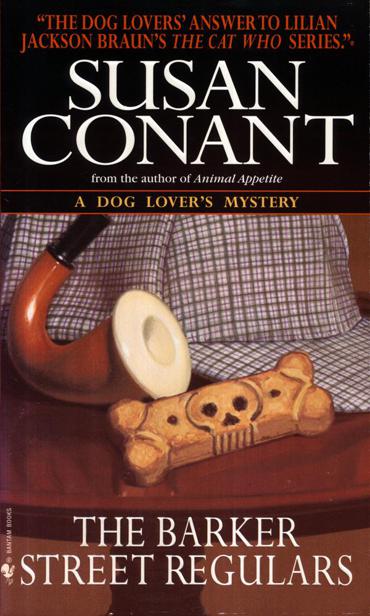

The Barker Street Regulars

Steve would arrive, if you could call it that, in the same state of stoical unavailability he’d been in since the beginning of the whole mess created by Gloria, Scott, and the so-called animal communicator, Irene Wheeler. Without even cleaning up the tuna and glass, I took a seat at the kitchen table and burst into tears.

Only a few minutes later, my second-floor tenant and dear friend, Rita, rapped on the door. If Rita weren’t a therapist by profession, she’d still be the kind of person everyone talks to, mainly because she has endless curiosity about people’s inner lives. Rita will spend eight or ten hours listening to her patients, arrive home exhausted, pour herself a drink, put her feet up, and then ask you how you’re feeling and really want to know. Now, however, the last thing I wanted was to tell Rita how I was feeling. All % wanted was not to feel it at all. I opened the door for Rita, anyway. She wore a new red coat and matching heels. Her hair had been freshly trimmed and lightly streaked. She looked so un-Cambridge, so New York, so groomed and manicured, so stylishly dressed, so accessorized, as she says, that by comparison I felt like the pile of broken Pyrex and dead fish still lying on the floor.

“What’s wrong?” she asked. “The dogs! Did something happen to one of your dogs?”

“No, they’re fine, they’re in their crates, and I can’t let them loose because there’s a cat in here somewhere. Rita, someone kicked it and tried to drown it, and... This has been a horrible day from the second I woke up. One of my people at the nursing home died. She was ninety-three, but—”

“But you still didn’t want her to die,” Rita said. “Holly, I’m sorry, but I can’t talk now. I have a patient, and I have to run. I was just going to pop in to ask what you know about finding lost dogs.”

“Willie?” Willie is Rita’s Scottie. “He was barking twenty minutes ago.”

“A dog of one of my patients. She’s frantic. I thought you might have some idea of how she should go about—”

Ordinarily, I’d have told Rita to have her patient call me, and I’d have swamped Rita with advice about posting photographs, informing every dog officer in the state, advertising in the papers, organizing brigades of friends, and alerting those champion finders of lost dogs, neighborhood children. Now, I just went into my study, found a handout on the topic, gave it to Rita, and said that I hoped her patient found the dog. After offer-mg another apology for having to leave, Rita rushed off.

Rita is a natural therapist. After her departure, I began to pull myself together. I swept the floor and vacuumed up every bit of broken glass. The dogs, I realized, didn’t have to remain in their crates. I led them, one at a time and on leash, to the door to the fenced yard. I made myself a sandwich out of the New York sharp cheddar that I use to train the dogs. The cheese was manufactured for human consumption, I re-minded myself; I hadn’t yet descended to lunching on liver treats. I had a cup of strong coffee that fortified me for a systematic search for the cat, which I finally found in the first place I should have looked: the long, narrow space between the head of my king-size bed and the wall. When Kimi steals food too big to wolf down in one gulp, it’s where she dens up to gnaw her booty. I can usually lure her out with a combination of food and the word Trade! spoken in an enthusiastic, talking-to-dogs tone of voice. If there’s a talking-to-cats tone, I haven’t mastered it. Lying flat on my stomach, I peered in at the cat, whistled softly, made stupid clucking noises, drummed my fingers lightly on the floor and offered bits of cheddar and tuna. I got nothing for these efforts but a kink in my neck and a couple of loud hisses.

“The thing about making a fool of myself with dogs,” I told Kevin Dennehy a half hour later, “is that I get results. Now here I am stuck with this cat under the bed, and I can’t get the damn thing to come out.”

Kevin was seated at my kitchen table sipping Bud out of the can. Indeed, it occurs to me that I can introduce Kevin, and Cambridge, too, as Caesar introduced Gaul. Thus all Cambridge is divided into three parts, of which one drinks mineral water, the second imported I wine, and the third what in Kevin’s language is called Bud, in mine beer. In this context, as one writes in Cambridge, let me add that the connection between Kevin and the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher