![The Barker Street Regulars]()

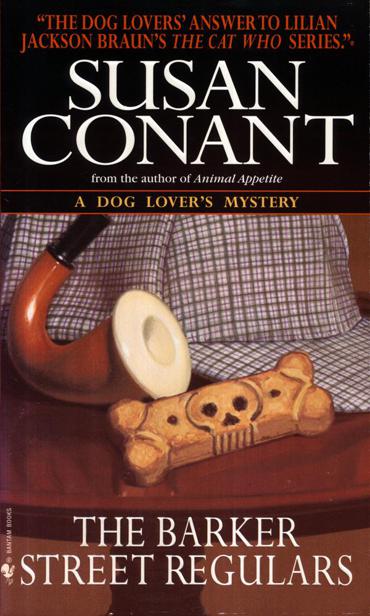

The Barker Street Regulars

Meryl Streep, if not the Toby or Pompey, of malamutes. She was far more convincing than Rowdy’d have been. If offered the scarf, Rowdy’d have taken it in his teeth and administered a death shake. Kimi, however, having been given the opportunity to take the scent, preceded me through the French door that Hugh held open. Once outdoors, she chose the route that Hugh, Robert, Ceci, and I had taken, probably the one followed by Jonathan and subsequently by the detectives, crime scene technicians, and other official investigators of the murder. Somewhat to my disappointment, Kimi did not keep her nose to the ground. Still, the combination of her characteristic self-confidence and the long, taut tracking lead fastened to her harness created the happy impression of a dog who knew what she was doing. It’s remotely possible that she did. Technically, a tracking dog follows footsteps step by step, and a trailing dog works near the track, but an air-scenting dog goes after scent wherever it’s available, on or above ground, and doesn’t fit the Hollywood image of a bloodhound at work. The sense of olfaction, of course, is thousands, millions, or even billions of times more acute in dogs than in human beings. According to those who believe in the occult, all objects, inanimate as well as animate, retain information about everything they’ve ever been exposed to. Walls not only have ears, but can speak to those gifted with the power to hear, especially, if you ask me, if those gifted with the power to hear are paid lots of money and convey interesting messages about the exalted or fascinating personages their clients were in past lives. The only thing no one was in a past life is boring. You have to wonder whatever happens to dull souls.

Anyway, to the nose of the dog, all objects really do communicate history. Or at least relatively recent history. There was no question that Kimi was perceiving my scent, the trails of Hugh, Robert, Ceci, the authorities, and Jonathan, too, as well as the myriad scents of everything from dormant insects underground to the aromas of the dinners recently cooked and consumed by Ceci’s neighbors on Norwood Hill. I had no faith that Kimi was discriminating between Jonathan’s scent and each of a zillion others.

“Air scenting,” I remarked... well, airily.

Ceci’s property, as I’ve explained, sloped down from Upper Norwood Road, where her house was, to an evergreen hedge and the gate in the fence that opened to Lower Norwood Road. Jonathan’s body had been found near the bottom of the yard, by the sundial that marked the burial place of Simon’s ashes. It seemed to me that if Kimi actually was looking for Jonathan or anything that bore his scent, she should veer off the bluestone path and make for the area near the sundial where his corpse had lain. According to one theory of how dogs track, what the animal follows isn’t the odor of the breathing, sweating person, but the scent of the microscopic flakes of skin that fall off all of us all the time and subsequently get eaten by bacteria and decompose. It seemed to me that if we, the living, went around repulsively scattering this dandruff that reeked in our paths in a manner we’d all prefer to ignore, well, what about corpses? I mean, most bodily functions don’t rev up and switch into high gear after death. Shedding, I thought, should be an exception. As in “shuffled off this mortal coil”?

I was pondering the inspiration for the image—did Shakespeare have a dog? a pet snake? dandruff?—when Kimi abruptly turned off the path and headed for the sundial. As she neared it, her demeanor changed. She slowed her pace, lowered her head, and put her nose to the frozen grass. Instead of casting about in some bodyshaped area near the sundial, however, she worked her way to within an inch of its base. Ears alert, nostrils twitching, she concentrated intently on the ground. Then with an air of fascinated deliberation, she patiently sniffed her way up the stone pedestal to a height of about a foot and a half. There, her nose lingered briefly before beginning its delicious descent. A year or two earlier, I’d watched a TV show about the ritual banquet of a society in France called La Confrérie des Chevaliers du Tastevin. What struck me was the familiar expression of rapture on the faces of the chevaliers as they savored the bouquets of their wines. With an almost snobbish sense of pride, I realized that when it came to ecstasy in

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher