![The Beginning of After]()

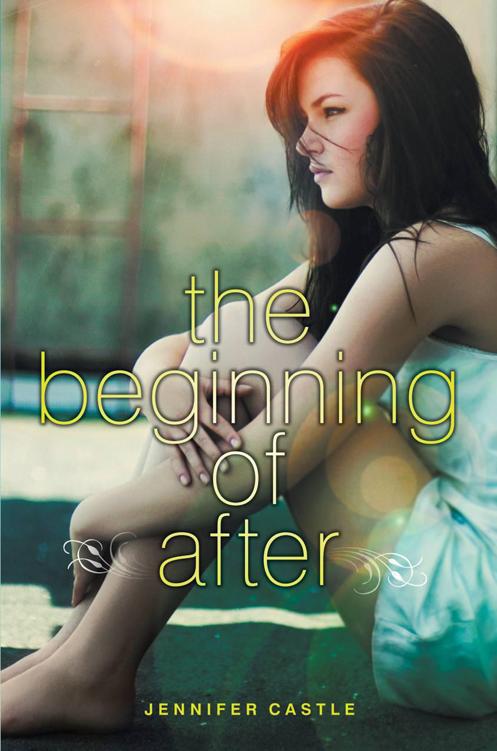

The Beginning of After

stand outside with the door closed.

“Ha!” I said out loud to nobody.

I’d gotten in.

I thought of how my dad’s face might have looked at the news. He was good at the knowing smile; I think he would have done that. And he got misty so easily, never afraid to leave the tears there and not wipe them away.

What about Mom? She’d be surprised, first. Genuinely surprised, and that would piss me off a little. And then she’d look relieved and laugh, and I’d just laugh back to forget the pissed-off part.

They’re with you right now , I told myself. They’re here.

When Nana came to find me ten minutes later, I was still crying.

“I remember when your dad got his letter,” said Nana over our celebration half-plain, half-veggie pizza at Vinny’s. “He wasn’t sure he wanted to go, but he heard the girls were particularly pretty there.” She paused, the corners of her eyes glistening. “He would be so proud, you know.”

I nodded and looked down, then decided, to hell with it. No time like the present.

“Nana, I’m not sure I should go.”

She put down her slice of pizza, taking a moment to arrange it neatly in the center of the plate, and frowned at me. “Why wouldn’t you go?”

“I mean, maybe I’m not ready to live away from home. Instead I could go to Columbia or NYU, which are both great schools, if I got in. And I could stay here.” Then I added, because I thought maybe it would help, “With you.”

How could I tell her the things that had been swimming in my head all afternoon? The things I didn’t even want to think about before, because I didn’t have to, but now I had to. It would have been easier to get rejected from Yale so I could keep on not thinking about them.

What about the animals? Not just Selina and Elliot and Masher, but the patients at Ashland and the future Echos who might need me to be on the other end of a phone call. Echo was the cat I’d picked up from the shelter and brought to Ashland that day after Thanksgiving. Eve already had a possible home for her.

But there was another thing. It had come up during a session with Suzie the previous week.

“Are you excited to hear about Yale?” asked Suzie, looking at her notes.

“I guess so,” I’d answered, looking out the window. It felt like small talk.

“You’re not sure?”

“No, I’m sure.” I hated these idiotic conversations we had sometimes.

“Laurel,” said Suzie, pausing carefully, “do you feel you’re ready for your future?”

I’d just looked at her.

“Because that’s normal. To feel anxious about moving on, continuing with your life, when people you love are gone.”

All I’d said was, “Okay, I get that.” I found that Suzie got quiet and satisfied after I said this. Our sessions had less talking these days, and we were always ending early.

Finally, I thought of an answer for Nana.

“I’m just worried about you. Won’t you be lonely if I go away?”

Nana had picked up her pizza slice, but now she put it down once more. “I will miss you, yes,” she said. “But honestly, Laurel, if you’re in New Haven, it means I can spend the fall and winter in Hilton Head. I won’t have to sell the condo.”

“So you want to get rid of me?” I asked, trying to make it sound jokey.

“No. I want you to go get the terrific education your parents always dreamed of for you.”

She choked up, which made me choke up, and we both took bites of pizza in silence.

At home, I picked up the phone to call Meg to tell her the news, then stopped myself. It had been three weeks since that morning, the Morning of Save-a-Cat-or-Meet-Meg-at-the-Mall, and when we were together, we were like actors in a play. At school, in the hallways or in the classes where we still sat next to each other out of habit, we played the scripted roles of best friends. Lending each other pens, waiting for each other in doorways and by lockers. Making small talk about how hard the math test was and how awful our hair looked.

But outside of school, that phone line was still dead. Meg no longer offered me rides anywhere. She didn’t stop by to hang out, or invite me to her house. She didn’t call or text me late at night to tell me about Gavin or Andie or especially her parents.

I missed her like crazy, but I was also stubborn. I knew I had been right. Echo had been more important. Echo, with the wide black stripes like she’d been painted with a thick sponge brush, who liked to lick your forearm while you

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher