![The Chemickal Marriage]()

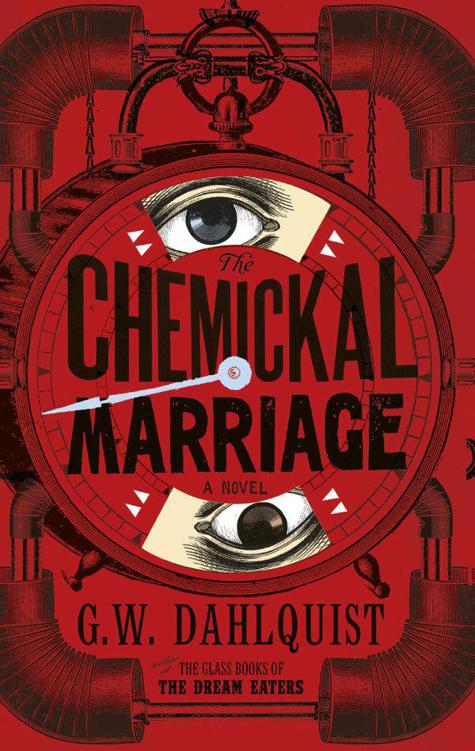

The Chemickal Marriage

billowing effervescence. The Ministry men hovered, one, stuck between care and complicity, arm in arm with the Duchess, for Schoepfil dared not leave her alone. Another held the lantern high, but the cavern had no other exit but the pool.

Svenson gave the candle a glance, noticed the ash around its base and the tiniest curl of unburnt paper, coloured red. The Contessa had left a message, which Miss Temple had possessed the presence of mind to burn.

The riddle of the clothing was even simpler: one woman had followed the lead of the other, the clothing removed to swim. Svenson knelt at the water, swiped a finger through the fizz and put it to his nose, then in his mouth.

‘Colder than the baths,’ he said, ‘though the minerals prove a mingling. This channel meets the river. Underground.’

‘It was a secret way,’ said the Duchess. ‘Used for terrible things.’

He did not suppose any explanation was needed; they were beneath a palace, after all. ‘The journey to air cannot be far. Do we follow?’

He plucked his tunic between his thumb and forefinger, as if offering to strip. Schoepfil scowled. ‘Of course we don’t. The ash there, Kelling – what was burnt?’

‘A note. Unreadable, sir.’

‘Blasted female. Shameless. Brazen.’ Schoepfil pointed damningly at the clothes. ‘Does she have a new wardrobe ready on the other side? Of

course

she does. And as soon as your little

beast

arrives she will also have my

book

!’

Svenson had thought Miss Temple dead, only to see her again in the baths – with the Contessa, of all people, and being introduced, of all things, to the sickly, costive Queen. From their concealment he and Schoepfil had heard the entire conversation, the Contessa’s sly blaming of Vandaariff and Lord Axewith for the Duke of Staëlmaere’s murder. Minutes later came Colonel Bronque’s own audience, a litany of abuse received in place of Axewith, whose request for the Queen’s seal was violently refused. Schoepfil had nearly exposed their hiding place, chuckling at this reverse for his uncle. Uncle! What but a life of envious proximity to power could explain this strange creature of a man?

From there Svenson had been passed to the odious Kelling, who – with two grenadiers – had shown him another cork-lined room stuffed with ephemera relating to the Comte d’Orkancz and indigo clay: books and papers, diagrams, paintings, half-tooled bits of brass and steel. Kelling hungrily noted where his attention fell, as if Svenson were a pilgrim in an alchemical allegory, presented with a table of riches, with his choice to dictate the course of his soul.

‘Lorenz.’ Svenson tapped a stack of that man’s notes. ‘Dropped out of an airship to the freezing sea.’

Kelling was silent. Svenson moved to the next pile.

‘Fochtmann. Shot in the head at Parchfeldt.’ He smiled at Kelling, as if in friendly reminiscence. ‘Gray, killed at Harschmort by Cardinal Chang. And Crooner … everyone forgets him. Lost both arms – turned to glass and sheared off. Died of the shock, I suppose …’

‘What about the

marriage

?’ Kelling extended his knobbed throat like a buzzard.

‘Do you mean the painting?’

‘Do I?’

‘Or the ritual behind it?’ Svenson smiled pleasantly. ‘A man like the Comte d’Orkancz would view the thing as a

recipe

. Since he was barking

mad

.’

Svenson fished out a rumpled cigarette and, not waiting for Kelling’s permission, set it to light. He exhaled. ‘Do you know what

happened

to the Comte?’

‘He died on the airship,’ replied Kelling.

Doctor Svenson took another puff and shook his head. ‘No, Mr Kelling. He is in

hell

.’

He was taken by the grenadiers to another room, Kelling called away and, to Svenson’s mind, happy to leave. Kelling was exactly the sort of court-bred toad whose dislike the Doctor had so often negotiated in protecting the Prince, men whose self-regard became one with their masters’. Svenson’s refusal to be so

attached

had marked him a social leper.

But worse than the company of Kelling was that of his own untendedheart. Left alone, the guilt Svenson had been able to suppress since his delivery to Schoepfil rose to the surface of his thought. Francesca. Elöise. The Contessa.

A soldier entered with a wooden plate of bread and meat, and a mug of beer. Svenson drank half the beer in a swallow and set the plate on his lap, forcing himself to chew each bite. The bread had gone stiff, sliced hours before, and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher