![The Glass Room (Vera Stanhope 5)]()

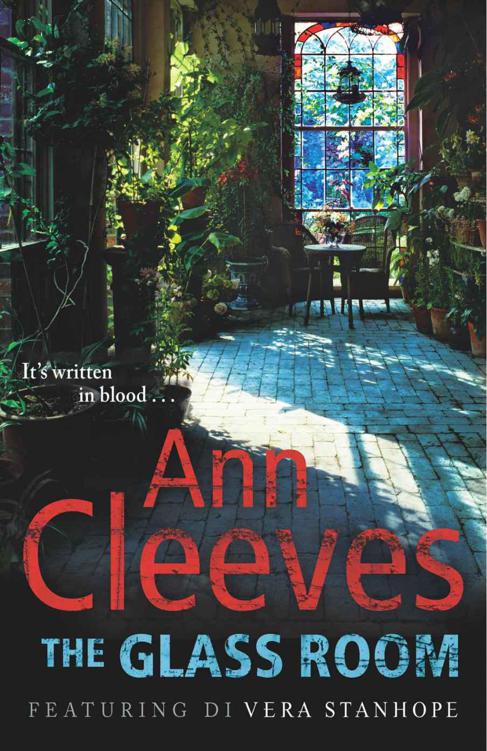

The Glass Room (Vera Stanhope 5)

chatting and laughing. She hesitated long enough to discover that they were there to search the gardens. All day she would catch glimpses of them, walking in lines across the lawns and through the trees.

Alex had moved inside and was clearing the grate in the drawing room. He was bending over the fireplace sweeping the last of the ash into a big, flat rusty dustpan. He was wearing jeans and a tight black T-shirt. Nina had noticed before that he never seemed to be affected by the cold.

He heard her come in and turned round. ‘Sorry. I should have done this last night. But after all that happened . . .’

‘How’s Miranda this morning?’ Really, Nina didn’t care how Miranda was feeling. She’d taken a dislike to the woman from the minute she’d arrived here. From before that, even. But it seemed the right thing to say.

He straightened. He’d tipped the ash into a metal bucket. ‘She’s okay. It’s not as if she was particularly close to Tony. Not recently. I don’t think they’d had much to do with each other professionally for years. It was the shock, I suppose, that made her so hysterical.’

‘Oh, I thought they were great friends.’ That, certainly, was the impression Ferdinand had given all those years ago.

Alex looked up sharply. ‘Once perhaps. Not now.’

Nina brought out her notes. This was her standard lecture on the structure of the short story. She’d given it so many times that she could deliver it standing on her head. She looked at her watch. Ten minutes to go. Soon the keen ones would be dribbling in.

An hour later they stopped for coffee. The lecture had gone well enough. The students had laughed in the right places, had seemed focused, had taken notes. Nina enjoyed teaching mature students more than she did lecturing to undergraduates, who were usually super-cool and unengaged. And yet this morning she had the sense that they were all just going through the motions. Wasn’t everyone actually thinking about a real crime while she’d been speaking of fiction?

‘Storytelling is all about what if? ’ she’d said. ‘ What if this character acts in this particular way? What if things aren’t quite what they seem?’

Now, drinking her black decaff coffee, listening to the murmured conversation all around her, she thought she had her own questions, which could affect the narrative of these particular events: What if Joanna Tobin didn’t kill Tony after all? What if I tell the detective everything I know about Tony Ferdinand?

After the break she set the group an exercise. The room was quiet and warm, from the background heat of the radiators, but also from the sun that flooded in through the big windows. Nina found that she was drifting into a daydream, part memory and part fantasy. This is what writers do, she thought. We create fictions even from our own experience. None of our recollections are entirely reliable. For she considered herself a writer, even though her work was only published by a small independent press based in the wilds of Northumberland.

In her story (or her memory) she was twenty-one, a bright young woman, newly graduated with a First in English literature from Bristol University. She spent the summer in her grandparents’ home in Northumberland, working in the local pub every evening and writing during the day. A novel, of course. A great young woman’s novel about growing up and love. It had been a joyous book, Nina thought now – the writing as glittering as the water had been that wonderful summer, when she sat in the garden of her grandparents’ house, with her laptop on the rickety wooden table, tapping out her 2,000 words a day. She would be far too cynical to write a novel like that now. And her grandparents had watched admiringly, interrupting only to bring her cold drinks, bowls of raspberries from the garden, slices of home-made cake.

Nina stirred in her chair and glanced at the clock. The time she’d allowed her students for the exercise was over. Now they would read their work aloud and she would find something intelligent, helpful and kind to say about it. Her own story would have to wait for another occasion.

The fat detective appeared suddenly at lunchtime. She was there with the good-looking sidekick, ladling soup into her bowl, as if she hadn’t eaten in weeks, chopping off thick slices of newly baked bread and spreading it with butter.

Nina watched her from the other side of the table. She tried to listen in to the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher