![The Glass Room (Vera Stanhope 5)]()

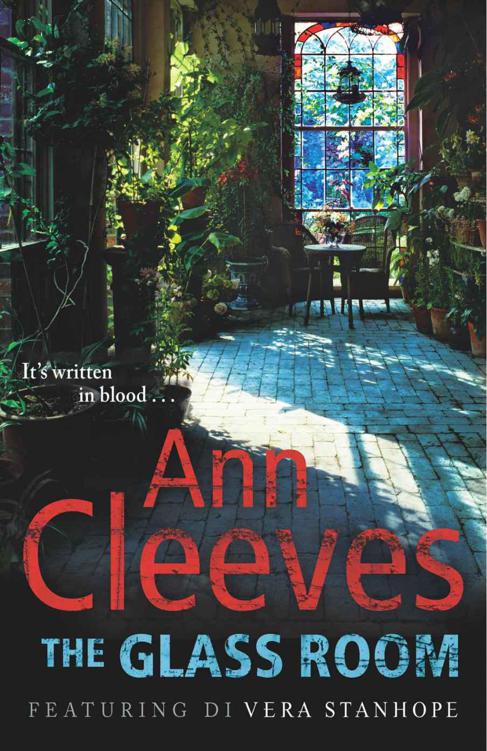

The Glass Room (Vera Stanhope 5)

Holly, you start chivvying the publishers. I need to know what Miranda was up to. That’s our priority at the moment.’

Joe went, secretly pleased to have an excuse to see Nina again, but offended too that Vera hadn’t decided to confide in him. Usually she was happy enough to share her daft ideas. When he arrived in Newcastle he sat for a moment outside the house where Nina lived. By now it was lunchtime and girls from a private school at the end of the road were walking along the pavement, giggling and scuffing the fallen leaves with their feet. He waited until they’d passed, then he got out of the car and rang the bell.

He thought Nina must be dressed for work. She seemed to him very smart.

‘This is such a nuisance.’ Her voice was peevish. ‘I’ve already had to cancel my class at the university, and I’m supposed to be doing a radio interview this afternoon.’

‘It won’t take long.’

Suddenly she put her head in her hands. ‘Oh God, I’m sorry. It’s not your fault and it was good of you to come. I’m scared. Absolutely bloody terrified. Waking up in the middle of the night to find someone in the flat. I thought I was going to die like the others.’

‘Of course you’re scared.’

She led him into a large living room with a deep bay window. All the furniture was old. One wall was covered in books. There was a table under the window, where long blue velvet curtains reached almost to the floor. And on the floor a grey carpet.

‘It looks very tidy,’ he said. ‘You’ve not moved anything?’

‘Don’t you believe me?’ She turned on him and he saw how close she was to hysteria.

‘Of course I believe you. Has anything been taken?’

She shook her head. ‘Not that I can tell.’

He thought she would know if anything was missing. This was an ordered place. She was an organized woman.

‘They did bring something, though.’ She pointed to a glass bowl, containing small fruit. They were so perfect that if it hadn’t been for the smell, he’d have thought they weren’t real, that they were wood or china, painted. ‘They were there, left by the intruder. He meant to leave them. That’s why he came in here first. He was on his way to the bedroom when the siren frightened him off.’

‘Apricots, are they?’ He wondered if she was losing her mind. She’d been so tense when he’d last seen her, so strung out, that he wouldn’t have been so surprised.

‘Yes.’

‘Why would a burglar bring you apricots? You must have bought them before you went away and forgotten all about them.’ He kept his voice gentle. ‘You can tell by the smell that they’re very ripe. They could have been here a week.’

‘I didn’t buy them,’ she said. She was frowning and a little angry, but he thought that she was quite sane after all.

‘There’s no sign of a break-in.’ He took a seat on a scratched leather chair.

‘No, and I don’t get that, either. It’s like he’s some ghost who can walk through walls.’

‘More likely someone who’s got hold of a key,’ Ashworth said. ‘Did you have a spare? Have you ever given one to a friend?’ He was thinking that the fruit could be a message. From a lover, maybe. Or a drunken student thinking it would be funny to scare his teacher. This might have nothing to do with the Writers’ House investigation after all.

‘No, I’ve never given a key away. I’ve always lived here alone.’

‘But you’ll have a spare? Could you check it for me, please?’

‘My neighbour has one in case of emergencies. But Dennis has been here as long as I have. He wouldn’t play this kind of stunt.’

Dennis was a small, tidy man in his sixties. He’d worked as an engineer in the shipyards, moved into the garden flat below Nina when his wife had died. Nina filled in the background information as they went downstairs. They found him sweeping leaves in the yard at the front of his flat. Nina told him about the break-in and asked about the key.

‘It’s hanging up in the kitchen where it always is, pet.’ He seemed affronted, as if Nina had accused him of committing burglary. ‘See for yourself.’ He led them through an arched gate at the side of the house and in through the open kitchen door. Over the sink there was a row of hooks, each neatly labelled. The one marked Nina was empty.

‘Not a ghost then,’ Ashworth said. They were back in Nina’s flat and she’d made coffee and a sandwich. It was a poor sort of joke, but he wanted to make

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher