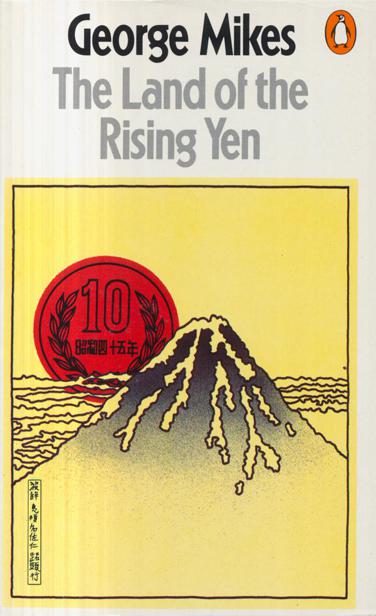

![The Land od the Rising Yen]()

The Land od the Rising Yen

produce

their second-rate little cars, this concentration on industry will keep them

out of serious mischief. They did continue, they kept the Western trade names

for many of their products but — to our surprise and often hardly concealed

annoyance — their products kept on improving. A few years after the war people

said about Japanese cameras: ‘Well, not bad for the price.’ Then it became

widely known that the lenses were superb, perhaps the best in the world, but

the rest — shutters, built-in exposure meters etc. — were somewhat inferior.

But before long Japanese cameras improved further and gained an excellent,

all-round reputation — yet remained very competitive in price. Similarly, we

tried out their cars and nodded benevolently: ‘Not bad,’ which in this

exceptional case meant what it should mean: not bad but not really good. We

were right: even five or six years ago they were not outstanding. Today they

are.

The Japan Times has a slogan

printed on its front page: ‘All the News Without Fear and Favor’. Being a good

Westerner, I smiled at this at first. It was, of course, a childish imitation

of the New York Times slogan: ‘All the News That’s Fit to Print’. A mere

rewording. And why have a slogan, in the first place? The overwhelming majority

of newspapers appear without slogans and (with regrettable exceptions) survive.

But after a few days I came to regard this slogan in the Japan Times as

a prototype of Japanese treatment of imported methods and ideas. Imitation?

Certainly. Mere childish rewording? Most certainly not. The New York Times is one of the world’s great papers but its slogan is arrogant. Fit to print?

Who will decide for you and me what is ‘fit to print’? Who will censor the news

for us, and on what grounds, on the flimsy pretext that it is not fit for us to

see? What the New York Times meant — and practises — is exactly what the Japan Times proclaims: ‘All the News without Fear and Favor’. No

goodwill or admiration could call the Japanese slogan original; no malice can

deny the improvement.

So what about imitation? We should

remember, first of all, that all knowledge is imitation. The baby learns to

walk and talk through imitation; man learnt how to build better houses and how

to improve on his agricultural methods because he imitated his neighbour or the

neighbouring — often previously conquered — tribes; millions of books from the

simpler do-it-yourself kind up to the most complicated treatises instructing us

how to build spacecraft, teach us how to imitate others. In some cases we call

imitation knowledge; in others we call knowledge imitation. The Japanese in

their wild quest for knowledge, in their insatiable desire to learn, made the

imitative aspect of their learning more obvious than most other people. But all

who learn imitate.

Even today: when we copy

things American we follow the fashion; if the Japanese do it, they imitate.

While imitation was sometimes a

euphemism for unscrupulous stealing of rights and ideas, in other — later —

cases it was a pejorative term for learning. There is nothing wrong, per se, in imitation and I think the time has come when we should start imitating the

Japanese. There are quite a few things we could learn from them to our benefit.

What? one may ask. Many technical

innovations and improvements but those are not what I have in mind. We ought to

imitate their courtesy; their respect for privacy (respect for privacy, yes:

about lack of privacy see later); their veneration of old age; their loyalty —

loyalty to families, firms, all the groups they belong to; their pride in their

work; their sense of beauty and their cultivation of it in everyday, trivial

things; and also their gentleness.

THE BRUTALITY OF GENTLE PEOPLE

The mention of gentleness must have

caused many brows to be raised. Gentleness indeed? These people whose brutality

was notorious have suddenly become gentle? And we should imitate their

gentleness?

After spending some time in Japan, one would still be puzzled but would word the same question differently: how could

these smiling, bowing, courteous, gentle people behave with such unspeakable brutality

as they did? Because there is no denying it: they did.

It is vaguely connected with their

devotion to imitation. Some people try to explain it in this simple way. Every

significant event in Japanese history seemed to point a moral. Foreigners could

force Japan open? Then — said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher