![The Lesson of Her Death]()

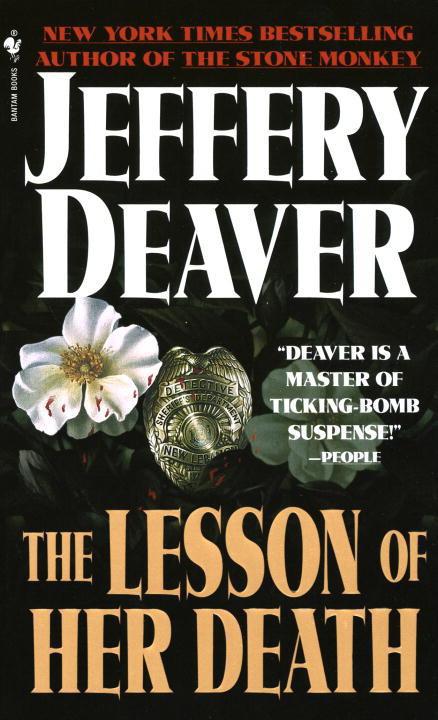

The Lesson of Her Death

Randy Sayles said, “I have a lecture.”

“He said it’s now’r never.”

“A LECTURE!”

“Professor,” the departmental secretary said, “I’m only reporting to you what he said.”

“Shit.”

“Professor. There’s no need to be vulgar.”

He sat at his desk at nine o’clock in the morning, gripping the telephone receiver in his hand as if he were trying to squeeze out an answer to the dilemma. Sayles’s last lecture of the year was scheduled to begin in one hour. It was set against the centennial celebrations throughout the U.S. in 1876. The climax was a spellbinding account (his students’, not his, review) of the Custer massacre. For him to miss this particular class was obscene. This fucko fund-raising crap had totally disrupted his teaching and he was torrid with rage.

He said, “Tell him to hold.” He dialed the dean. Her secretary said she was out.

“Shit.”

Yes, no, yes, no? Sayles said into the receiver, “Okay, I’ll see him. Get Darby to take over for me.”

“The students will be disappointed.”

“You’re

the one who told me it was now or never!”

She said, “I was only—”

“Get Darby.” Sayles banged the phone down and ran from his office, hurrying to his car. As he roared out of the professors’ parking lot, he laid down two streaks of simmering rubber as if he were a sixteen-year-old in a stolen ’Vette.

He paced across the gold carpet, staring down at the stain made by the cola Sarah spilled the night Emily was murdered.

“Oh, Bill.”

“It doesn’t mean I’m fired. I still draw pay.”

“What were these letters?”

“Who knows? We found ash. We found scraps.”

He looked up at his wife. Before Diane did something she dreaded, her eyes grew very wide. Astonishingly wide and dark as night. This happened now.

Bill Corde waited a moment, as if taking his temperature. The sense of betrayal never arrived and he said finally, “I didn’t take them.”

“No.”

He couldn’t tell how she meant the word. Was she agreeing? Or disputing him?

She asked, “They don’t know about St. Louis, do they?”

“I never told them.” He did not tell her that Jennie Gebben had known.

She nodded. “I should see about a job.”

“I told you I’m not fired. I—”

“I’m just thinking out loud. This is something—”

“Well, there’s nothing wrong with that.”

“This is something we have to talk about,” she continued.

But they didn’t talk about it. Not then at any rate. Because at that moment a squad car pulled into the driveway.

Corde leaned against the glass. He smelled ammonia. After a long moment the front door of the car opened. “It’s T.T. He’s got somebody with him, in the back. What’s he doing, transporting a prisoner?”

Ebbans climbed out of the squad car and unlocked the back door. Jamie slowly stepped out.

Halbert Strumm, who lived in an unincorporated enclave of Harrison County known as Millfield Creek, had made his fortune in animal by-products, turning bone and organ into house plant supplements, marked up a thousand times. Strumm would say with sincerity and drama that it brightened some stiff gelding’s last walk up the ramp to know he was going to be sprinkled lovingly on a tame philodendron overlooking Park Avenue in New York City. It was comments like this that kept Strumm held in contempt or ridicule by all the people who worked for him and most of the people who knew him.

Although he had not attended Auden University, Strumm and his wife Bettye had embraced the school as their adoptive charity. Their generosity however was largely conditional and they invariably looked for an element of bargain in their giving. Off shot a check for a thousand dollars

if

they got subscription seats to the concert series. Five hundred, a stadium box. Five thousand, a trip to the Sudan on a dig with archeology students made wildly uncomfortable by the couple’s rollicking presence.

Now Randy Sayles, pulling into the Strumms’ driveway, was not sure if the couple was going to like the dealhe was about to propose. Strumm, a huge man, bald and broad, with massive hands, led Sayles into his greenhouse, and there they stood amid a thousand plants that seemed no healthier than those in Sayles’s own backyard garden, which did

not

gobble down the earthly remains of elderly animals. There was an injustice in this that depressed Sayles immensely.

“Hal, we have a problem and we need your help.”

“Money, that’s why

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher