![The Moment It Clicks: Photography Secrets From One of the World's Top Shooters]()

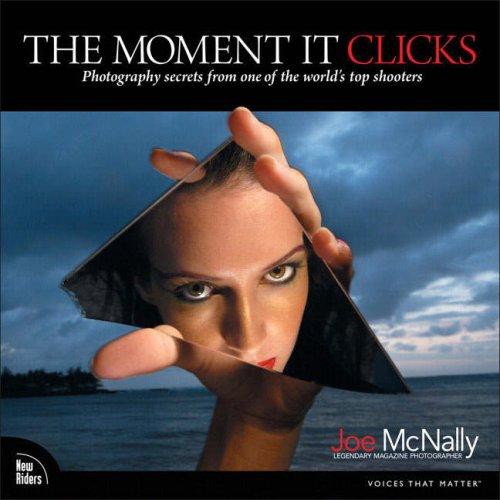

The Moment It Clicks: Photography Secrets From One of the World's Top Shooters

frames.

When we landed, I was standing with a bunch of astronauts on the ground, and my stomach dry heaved again. Heard chuckles all around. “Somebody wanna tell Joe here the flight’s over?”

Choosing Is Never Easy

“I wept for her, for me, but mostly because the siren call of my first big story with a yellow border around it was more powerful than the call of fatherhood.”

There needs to be a course in school about how to be a parent and a photographer. Not that we’d listen. All of that is so far away.

I missed a whole bunch of my kids’ growing up. Every traveling shooter does. I have a memory of a day when I was leaving for a four-week trip to Africa for National Geographic . My daughter Caitlin and I were in the driveway. It was hot and the sun was harsh. She was about three years old and had watched the familiar ritual of Dad loading the taxi to go to the airport many times.

I hugged her hard. Told her the usual things. She didn’t understand or care about what I was saying. I knew that. The things we say in these moments to our kids make us feel better, not them.

The cab pulled out and I twisted around and looked back, desperately waving. She couldn’t see me. The light was too bright. She waved once, and left her arm pressed against her forehead, shielding her eyes. The sun was glaring through the dirty window, and she faded from view, hot and yellowish, like an old Polaroid from the ‘50s.

I slid down in the seat and began to weep. I wept for her, for me, but mostly because the siren call of my first big story with a yellow border around it was more powerful than the call of fatherhood.

It’s All About Your Attitude

“The man was working at a feverish pitch. This was his pope, his moment, his country. He was making pictures he would tell his grandchildren about.”

The first papal trip to Poland was tough. The government was still Communist, Solidarity was getting feisty, and John Paul’s visit was fuel for that fire. The government put the squeeze on the press, hard.

They would, for instance, make it almost impossible to cover the pope, dropping us miles from the site of the mass, and erecting photo platforms so far from the altar you thought you were shooting a shuttle launch.

This went on for two weeks, a constant battering. I was at one mass in the countryside, and I had all the glass in my bag stacked on my camera, which meant a 400mm lens with a TC 1.4 converter with a doubler on top of that, and through all that the pope was still the size of a pea. To make matters worse, I was shooting in a driving rainstorm.

To add insult to injury, I was shooting for Newsweek , which meant I wasn’t connected. Time had the inside track, because Time had a contract photographer based in Rome. His main strengths were not photographic. He knew how to work the Vatican. He had the place wired.

I’m out there with no picture to make, so just for grins I sweep the altar, poking around. And there, not more than 50 feet from the pope, is the Time guy. The kicker was not just his proximity, but the fact that there was a cardinal holding an umbrella over him while he shot.

My mood turned black. I became aware of another shooter, who had wedged in next to me, when the railing we were using for camera support started shaking. This guy was huffing and puffing, shooting like mad, and the whole platform was quivering. I turned, ready to tear somebody a new one, and stopped.

He had like a Novosiberskoflex, or some East bloc camera with a preset lens about half the focal length of my rig. It was a single-shot camera, wired with a cable release he had taped to the lens barrel. He had no right hand. He would focus left-handed, and steady the camera with his stump, then squeeze the cable with his good hand. Then he would reverse the grip and advance the shutter with his stump. The rail was shaking because of all this maneuvering.

The man was working at a feverish pitch. This was his pope, his moment, his country. He was making pictures he would tell his grandchildren about. I stood there, with a camera store around my neck, on assignment for a major international publication, and I had peevishly stopped working.

I felt ashamed. I put my eye back in the camera.

Listen to Your Assistant

Listen to your assistant. They can save your butt.

The baseball editor at Sports Illustrated looked at me and said, “I hate the baseball pictures. Go to Florida and

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher