![The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy With Autism]()

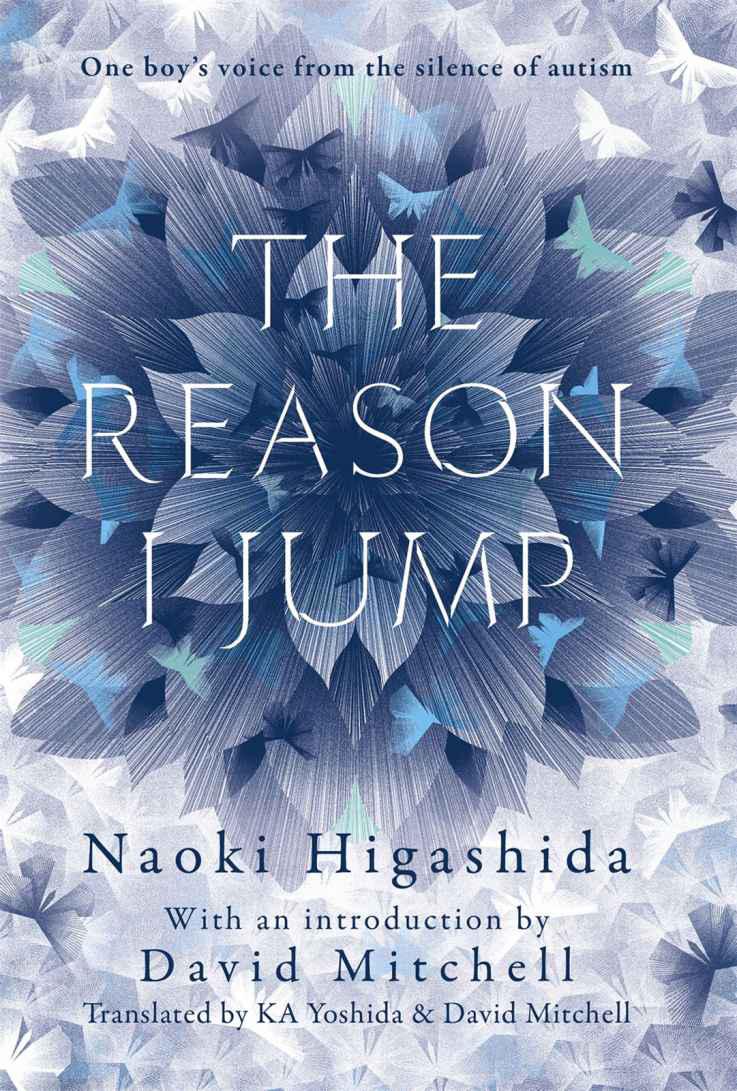

The Reason I Jump: The Inner Voice of a Thirteen-Year-Old Boy With Autism

your son still being the same little guy that he was before this life-redefining news was confirmed. Then you run the gauntlet of other people’s reactions: ‘It’s just so sad’; ‘What, so he’s going to be like Dustin Hoffman in

Rain Man

?’; ‘I hope you’re not going to take this so-called “diagnosis” lying down!’; and my favourite, ‘Yes, well, I told my GP where to go stick his MMR jabs.’ Your first contacts with most support agencies will put the last nails in the coffin of faintheartedness, and graft onto you a layer of scar-tissue and cynicism as thick as rhino-hide. There are gifted and resourceful people working in autism support, but with depressing regularity government policy appears to be about Band-Aids and fig leaves, and not about realising the potential of children with special needs and helping them become long-term net contributors to society. The scant silver lining is that medical theory is no longer blaming your wife for causing the autism by being a ‘Refrigerator Mother’ as it did not so long ago (Refrigerator Fathers were unavailable for comment) and that you don’t live in a society where people with autism are believed to be witches or devils and get treated accordingly.

Where to turn to next? Books. (You’ll have started already, because the first reaction of friends and family desperate to help is to send clippings, web-links and literature, however tangential to your own situation.) Special Needs publishing is a jungle. Many

How to Help Your Autistic Child

manuals have a doctrinaire spin, with generous helpings of © and ™. They may contain useable ideas, but reading them can feel depressingly like being asked to join a political party or a church. The more academic texts are denser, more cross-referenced and rich in pedagogy and abbreviations. Of course it’s good that academics are researching the field, but often the gap between the theory and what’s unravelling on your kitchen floor is too wide to bridge.

Another category is the more confessional memoir, usually written by a parent, describing the impact of autism on the family and sometimes the positive effect of an unorthodox treatment. These memoirs are media-friendly and raise the profile of autism in the marketplace of worthy causes, but I found their practical use to be limited, and in fairness they usually aren’t written to be useful. Every autistic person exhibits his or her own variation of the condition – autism is more like retina patterns than measles – and the more unorthodox the treatment for one child, the less likely it is to help another (mine, for example).

A fourth category of autism book is the ‘autism autobiography’ written by insiders on the autistic spectrum, the most famous example being

Thinking in Pictures

by Temple Grandin. For sure, these books are often illuminating, but almost by definition they tend to be written by adults who are already sorted, and they couldn’t help me where I needed help most: to understand why my three-year-old was banging his head against the floor; or flapping his fingers in front of his eyes at high speed; or suffering from skin so sensitive that he couldn’t sit or lie down; or howling with grief for forty-five minutes when the

Pingu

DVD was too scratched for the DVD player to read it. My reading provided theories, angles, anecdotes and guesses about these challenges, but without reasons all I could do was look on, helplessly.

One day my wife received a remarkable book she had ordered from Japan called

The Reason I Jump

. Its author, Naoki Higashida, was born in 1992 and was still in junior high-school when the book was published. Naoki’s autism is severe enough to make spoken communication pretty much impossible, even now. But thanks to an ambitious teacher and his own persistence, he learnt to spell out words directly onto an alphabet grid. A Japanese alphabet grid is a table of the basic forty Japanese hiragana letters, and its English counterpart is a copy of the QWERTY keyboard, drawn onto a card and laminated. Naoki communicates by pointing to the letters on these grids to spell out whole words, which a helper at his side then transcribes. These words build up into sentences, paragraphs and entire books. ‘Extras’ around the side of the grids include numbers, punctuation, and the words ‘Finished’, ‘Yes’ and ‘No’. (Although Naoki can also write and blog directly onto a computer via its keyboard, he finds the

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher