![The Rembrandt Affair]()

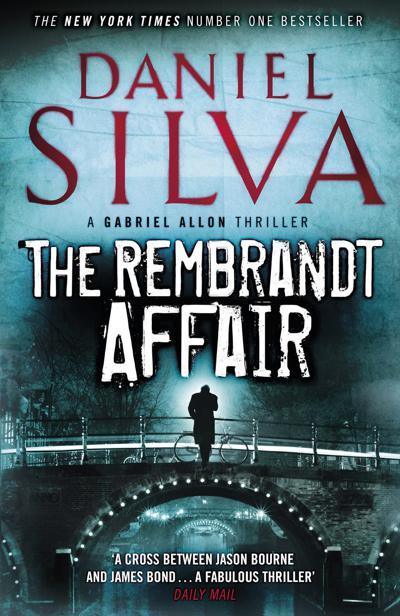

The Rembrandt Affair

the news was flattering since it would leave reporters several hours to research and write their stories. If the news were bad, the veterans postulated, Ramsay would have summoned the press corps hard against their evening deadlines. Or, in all likelihood, he would have released a bland paper statement, the refuge of cowardly civil servants the world over, and slipped out a back door.

Naturally, the speculation centered around the Van Gogh self-portrait pinched from London’s Courtauld Gallery several months earlier, although by that afternoon few reporters could even recall the painting’s title. Sadly, not one of the masterpieces stolen during the “summer of theft” had been recovered, and more paintings seemed to be disappearing from homes and galleries by the day. With the global economy mired in a recession without end, it appeared art theft was Europe’s last growth industry. In contrast, the police forces battling the thieves had seen their resources cut to the bone. Ramsay’s own annual budget had been slashed to a paltry three hundred thousand pounds, barely enough to keep the office functioning. His fiscal straits were so dire he had recently been forced to solicit private donations in order to keep his shop running. Even The Guardian suggested it might be time to close the fabled Art Squad and shift its resources to something more productive, such as a youth crime-prevention program.

It did not take long for the rumors about the Van Gogh to breach the walls of Scotland Yard’s pressroom and begin circulating on the Internet. And so it came as something of a shock when Ramsay strode to the podium to announce the recovery of a painting few people knew had ever been missing in the first place: Portrait of a Young Woman, oil on canvas, 104 by 86 centimeters, by Rembrandt van Rijn. Ramsay refused to go into detail as to precisely how the painting had been found, though he went to great pains to say no ransom or reward money was paid. As for its current location, he claimed ignorance and cut off the questioning.

There was much the press would never learn about the recovery of the Rembrandt. Even Ramsay himself was kept in the dark about most aspects of the case. He did not know, for example, that the painting had been quietly left in an alley behind a synagogue one week earlier in the Marais section of Paris. Or that it had been couriered to London by a sweating employee of the Israeli Embassy and turned over to Julian Isherwood, owner and sole proprietor of the sometimes solvent but never boring Isherwood Fine Arts, 7-8 Mason’s Yard, St. James’s. Nor would DI Ramsey ever learn that by the time of his news conference, the painting had already been quietly moved to a cottage atop the cliffs in Cornwall that bore a striking resemblance to the Customs Officer’s Cabin at Pourville by Claude Monet. Only MI5 knew that, and even within the halls of Thames House it was strictly need to know.

I N KEEPING with the spirit of Operation Masterpiece, her restoration would be a whirlwind. Gabriel would have three months to turn the most heavily damaged canvas he had ever seen into the star attraction of the National Gallery of Art’s long-awaited Rembrandt: A Retrospective. Three months to reline her and attach her to a new stretcher. Three months to remove the bloodstains and dirty varnish from her surface. Three months to repair a bullet hole in her forehead and smooth the creases caused by Kurt Voss’s decision to use her as the costliest envelope in history. It was an alarmingly short period of time, even for a restorer used to working under the pressure of a ticking clock.

In his youth, Gabriel had preferred to work in strict isolation, but now that he was older he no longer liked to be alone. So with Chiara’s blessing, he removed the furnishings from the living room and converted it into a makeshift studio. He rose before dawn each morning and worked until early evening, granting himself just one short break each day to walk the cliffs in the bitterly cold January wind. Chiara rarely strayed far from his side. She assisted with the relining and composed a small note to Rachel Herzfeld that Gabriel concealed against the inside of the new stretcher before tapping the last brad into place. She was even present the morning Gabriel undertook the unpleasant task of removing Christopher Liddell’s blood. Rather than drop the soiled swabs onto the floor, Gabriel sealed them in an aluminum canister. And

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher