![The Rembrandt Affair]()

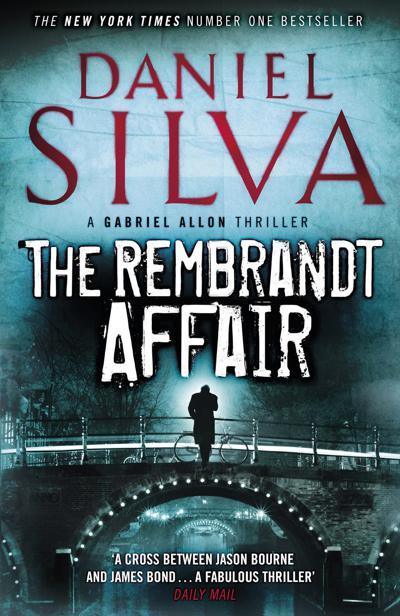

The Rembrandt Affair

in a corner rarely visited by guards or patrons. Using an old-fashioned razor, Durand sliced the painting from its frame and slipped it into his attaché case. Later, during the train ride back to Paris, he attempted to recall his emotions at the moment of the crime and realized he had felt nothing other than contentment. It was then that Maurice Durand knew he possessed the qualities of a perfect thief.

Like Peruggia before him, Durand kept his trophy in his Paris apartment, not for two years but for two days. Unlike the Italian, Durand already had a buyer waiting, a disreputable collector who happened to be in the market for a Chardin and wasn’t worried about messy details like provenance. Durand was well paid, the client was happy, and a career was born.

It was a career characterized by discipline. Durand never stole paintings to acquire ransom or reward money, only to provide inventory. At first he left the masterpieces to the dreamers and fools, focusing instead on midlevel paintings by quality artists or works that might reasonably be confused for pictures with no problem of provenance. And while Durand occasionally stole from small museums and galleries, he did most of his hunting in private villas and châteaux, which were poorly protected and filled to the roof with valuables.

From his base of operations in Paris he built a far-flung network of contacts, selling to dealers as far away as Hong Kong, New York, Dubai, and Tokyo. Gradually, he set his sights on bigger game—the museum-quality masterpieces valued at tens of millions, or in some cases hundreds of millions, of dollars. But he always operated by a simple rule. No painting was ever stolen unless a buyer was waiting, and he only did business with people he knew. Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear was now hanging in the palace of a Saudi sheikh who had a penchant for violence involving knives. The Caravaggio had found its way to a factory owner in Shanghai while the Picasso was in the hands of a Mexican billionaire with uncomfortably close ties to the country’s drug cartels. All three paintings had one thing in common. They would never be seen again by the public.

Needless to say, it had been many years since Maurice Durand had personally stolen a painting. It was a young man’s profession, and he had retired after a skylight assault on a small gallery in Austria resulted in a back injury that left him in constant pain. Ever since then he had been forced to utilize the services of hired professionals. The arrangement was less than ideal for all the obvious reasons, but Durand treated his fieldmen fairly and paid them exceedingly well. As a result, he had never had a single unpleasant complication. Until now.

It was the south that produced the finest wines in France and, in Durand’s estimation, its best thieves as well. Nowhere was that more true than the ancient port of Marseilles. Stepping from the Gare de Marseille Saint-Charles, Durand was pleased to find the temperature several degrees warmer than it had been in Paris. He walked quickly through the brilliant sunshine along the Boulevard d’Athènes, then turned to the right and headed down to the Old Port. It was approaching midday. The fishing boats had returned from their morning runs and atop the steel tables lining the port’s eastern flank were arrayed all manner of hideous-looking sea creatures, soon to be turned into bouillabaisse by the city’s chefs. Normally, Durand would have stopped to survey the contents of each with an appreciation only a Frenchman could manage, but today he headed straight for the table of a gray-haired man dressed in a tattered wool sweater and a rubber apron. By all appearances, he was a fisherman who scrounged a respectable living from a sea now empty of fish. But Pascal Rameau was anything but respectable. And he didn’t seem surprised to see Maurice Durand.

“How was the catch, Pascal?”

“Merde,” Rameau muttered. “It seems like we get a little less every day. Soon…” He pulled his lips downward into a Gallic expression of disgust. “There’ll be nothing left but garbage.”

“It’s the Italians’ fault,” said Durand.

“Everything is the Italians’ fault,” Rameau said. “How’s your back?”

Durand frowned. “As ever, Pascal.”

Rameau made an empathetic face. “Mine, too. I’m not sure how much longer I can work the boat.”

“You’re the richest man in Marseilles. Why do you still go to sea every

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher