![The Rembrandt Affair]()

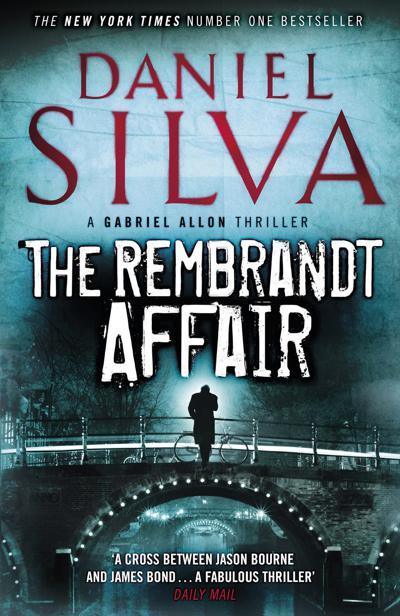

The Rembrandt Affair

documents had ever been stolen by his adversaries.

One section of the living room was largely free of historical debris, and it was there Ramirez received Gabriel and Chiara. Propped in one corner, exactly where she had left it the night of her abduction, was Maria’s dusty cello. On the wall above were two handwritten pages of poetry, framed and shielded by glass, along with a photograph of Ramirez at the time of his release from prison. He bore little resemblance to that emaciated figure now. Tall and broad-shouldered, he looked more like a man who wrestled with machinery and concrete than words and ideas. His only vanity was his lush gray beard, which in the opinion of right-wing critics made him look like a cross between Fidel Castro and Karl Marx. Ramirez did not take the characterization as an insult. An unrepentant communist, he revered both.

Despite the abundance of irreplaceable paper in the apartment, Ramirez was a reckless, absent-minded smoker who was forever leaving burning cigarettes in ashtrays or dangling off the end of tables. Somehow, he remembered Gabriel’s aversion to tobacco and managed to refrain from smoking while holding forth on an array of topics ranging from the state of the Argentine economy to the new American president to Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, which, of course, he considered deplorable. Finally, as the first drops of afternoon rain made puddles on the dusty windowsill, he recalled the afternoon several years earlier when he had taken Gabriel to the archives of Argentina’s Immigration Office. There, in a rat-chewed box of crumbling files, they discovered a document suggesting that Erich Radek, long assumed dead, was actually living under an assumed name in the first district of Vienna.

“I remember one thing in particular about that day,” Ramirez said now. “There was a beautiful girl on a motor scooter who followed us wherever we went. She wore a helmet the entire time, so I never really saw her face. But I remember her legs quite clearly.” He glanced at Chiara, then at Gabriel. “Obviously, your relationship was more than professional.”

Gabriel nodded, though by his expression he made it clear he wished to discuss the matter no further.

“So what brings the two of you to Argentina this time?” Ramirez asked.

“We were doing a bit of wine tasting in Mendoza.”

“Find anything to your liking?”

“The Bodega de la Mariposa Reserva.”

“The ’05 or the ’06?”

“The ’05, actually.”

“I’ve had it myself. In fact, I’ve had the opportunity to speak with the owner of that vineyard on a number of occasions.”

“Like him?”

“I do,” Ramirez said.

“Trust him?”

“As much as I trust anyone. And before we go any further, perhaps we should establish the ground rules for this conversation.”

“The same as last time. You help me now, I help you later.”

“What exactly are you looking for?”

“Information about an Argentine diplomat who died in Zurich in 1967.”

“I assume you’re referring to Carlos Weber?” Ramirez smiled. “And given your recent trip to Mendoza, I also assume that you’re searching for the missing fortune of one SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt Voss.”

“Does it exist, Alfonso?”

“Of course it exists. It was deposited in Bank Landesmann in Zurich between 1938 and 1945. Carlos Weber died trying to bring it to Argentina in 1967. And I have the documents to prove it.”

35

BUENOS AIRES

T here was just one problem. Alfonso Ramirez had no idea where he had hidden the documents. And so for the next half hour, as he shuffled from room to room, lifting dusty covers and frowning at stacks of faded paper, he recited the details of Carlos Weber’s disgraceful curriculum vitae. Educated in Spain and Germany, Weber was an ultranationalist who served as a foreign policy adviser to the parade of military officers and feeble politicians who had ruled Argentina in the decade before the Second World War. Profoundly anti-Semitic and antidemocratic, he tilted naturally toward the Third Reich and forged close ties to many senior SS officers—ties that left Weber uniquely positioned to help Nazi war criminals find sanctuary.

“He was one of the linchpins of the entire shitty deal. He was close to Perón, close to the Vatican, and close to the SS. Weber didn’t help the Nazi murderers come here merely out of the goodness of his heart. He actually believed they could help build the Argentina of his

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher