![The Rembrandt Affair]()

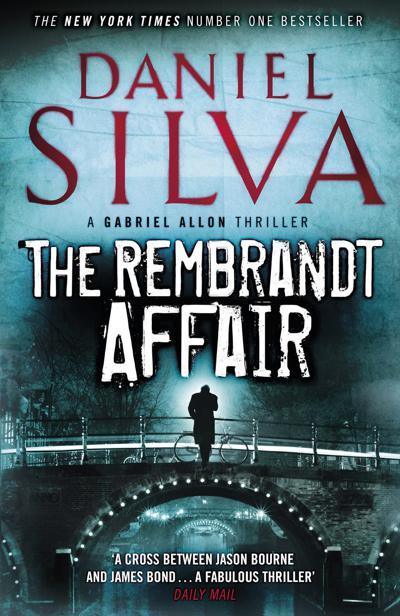

The Rembrandt Affair

minister refilled his coffee cup and contemplatively added a few drops of cream. Clearly, there was something he wished to say, but he seemed in no hurry to come to the point. Instead, he launched into a lengthy homily on the burdens of leadership in a complex and dangerous world. Sometimes, he said, decisions were influenced by national security, other times by political expediency. Occasionally, though, it boiled down to a simple question of right and wrong. He allowed this last statement to hang in the air for a moment before lifting his white linen napkin from his lap and folding it deliberately.

“My father’s family came from Hungary. Did you know that, Uzi?”

“I suspect the entire country knows that.”

The prime minister gave a fleeting smile. “They lived in a dreadful little village outside Budapest. My grandfather was a tailor. They had nothing to their name other than a pair of silver Shabbat candlesticks and a kiddush cup. And do you know what Kurt Voss and Adolf Eichmann did before putting them on a train to Auschwitz? They stole everything they had. And then they gave them a receipt. I have it to this day. I keep it as a reminder of the importance of the enterprise we call Israel.” He paused. “Do you understand what I’m saying to you, Uzi?”

“I believe I do, Prime Minister.”

“Keep me informed, Uzi. And remember, I like details.”

N AVOT STEPPED into the anteroom and was immediately accosted by several members of the Knesset waiting to see the prime minister. Claiming an unspecified problem requiring his urgent attention, he shook a few of the more influential hands and patted a few of the more important backs before beating a hasty retreat to the elevators. His armored limousine was waiting outside, surrounded by his security detail. Fittingly, the heavy gray skies were pouring with rain. He slipped into the back and tossed his briefcase onto the floor. As the car lurched forward, the driver sought Navot’s eyes in the rearview mirror.

“Where to, boss? King Saul Boulevard?”

“Not yet,” Navot said. “We have to make one stop first.”

T HE EUCALYPTUS TREE perfumed the entire western end of Narkiss Street. Navot lowered his window and peered up at the open French doors on the third floor of the limestone apartment house. From inside came the faint strains of an aria. Tosca? La Traviata? Navot didn’t know. Nor did he much care. At this moment, he was loathing opera and anyone who listened to it with an unreasonable passion. For a mad instant, he considered returning to the prime minister’s office and tendering his immediate resignation. Instead, he opened his secure cell phone and dialed. The aria went silent. Gabriel answered.

“You had no right going behind my back,” Navot said.

“I didn’t do a thing.”

“You didn’t have to. Shamron did it for you.”

“You left me no choice.”

Navot gave an exasperated sigh. “I’m down in the street.”

“I know.”

“How long do you need?”

“Five minutes.”

“I’ll wait.”

The volume of the aria rose to a crescendo. Navot closed his window and luxuriated in the deep silence of his car. God, but he hated opera.

41

ST. JAMES’S, LONDON

T he one name not spoken that morning in Jerusalem was the name of the man who had started it all: Julian Isherwood, owner and sole proprietor of Isherwood Fine Arts, 7-8 Mason’s Yard, St. James’s, London. Of Gabriel’s many discoveries and travails, Isherwood knew nothing. Indeed, since securing a set of yellowed sales records in Amsterdam, his role in the affair had been reduced to that of a worried and helpless bystander. He filled the empty hours of his days by following the British end of the investigation. The police had managed to keep the theft out of the papers but had no leads on the painting’s whereabouts or the identity of Christopher Liddell’s killer. This was not an amateur looking for a quick score, the detectives muttered in their own defense. This was the real thing.

As with all condemned men, Isherwood’s world shrank. He attended the odd auction, showed the odd painting, and tried in vain to distract himself by flirting with his latest young receptionist. But most of his time was devoted to planning his own professional funeral. He rehearsed the speech he would give to the hated David Cavendish, art adviser to the vastly rich, and even produced a rough draft of a mea culpa he would eventually have to send to the National Gallery

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher