![The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)]()

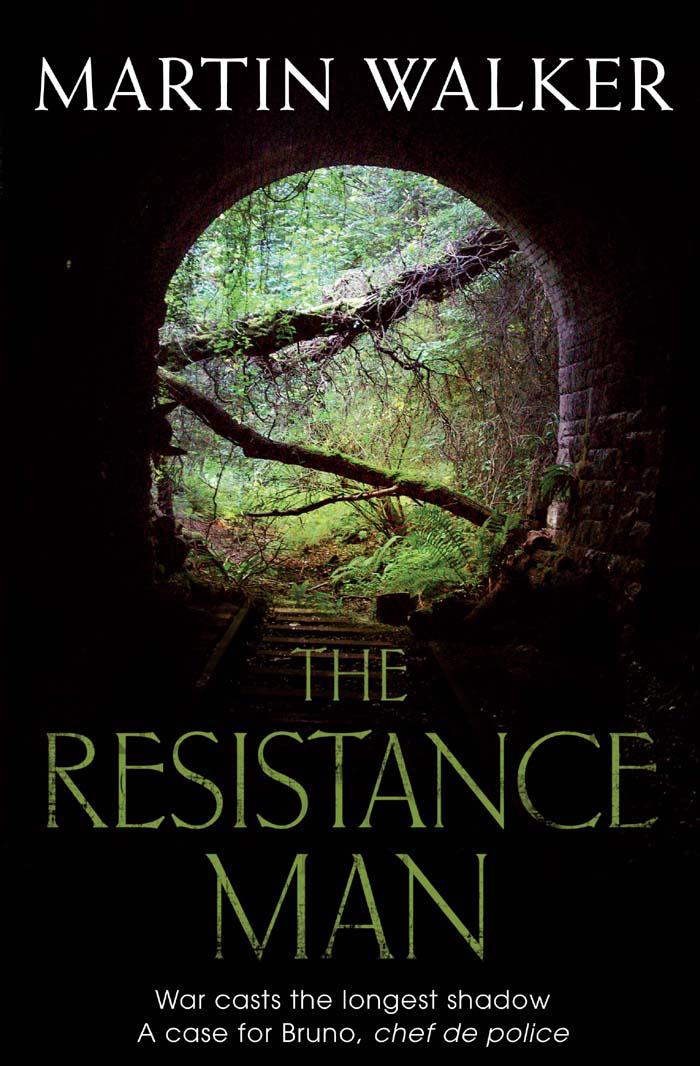

The Resistance Man (Bruno Chief of Police 6)

meet her and drive her back to St Denis. Pamela, who kept horses along with the

gîtes

she rented out to tourists, had been pleased to find in Fabiola a year-round tenant for one of the

gîtes

and the two women had become friends.

Bruno began making calls as soon as Fabiola and the priest left. He started with the veterans’ department at the Ministry of Defence to confirm a Resistance ceremony and then called the funeral parlour. Next he rang Florence, the science teacher at the local

collège

who was now running the town choir, to ask if she could arrange for the

Chant des Partisans

, the anthem of the Resistance, to be sung at the funeral. He rang the Centre Jean Moulin in Bordeaux, the Resistance museum and archive, for their help in preparing a summary of Murcoing’s war record. The last call was to the social security office, to stop the dead man’s pension payments. As he waited to be put through to the right department, he began to look around.

In the sitting room an old TV squatted on a chest of drawers. In the top one, Bruno found a large envelope marked ‘Banque’ and others that contained various utility bills and a copy of the deed of sale for Murcoing’s farm in the hills above Limeuil. It had been sold three years earlier, when prices were already tumbling, for 85,000 euros. The buyer had a name that sounded Dutch and the

notaire

was local. Bruno remembered the place, a ramshackle farmhouse with a roof that needed fixing and an old tobacco barn where goats were kept. The farm had been too small to be viable, even if the land had been good. Murcoing’s last bank statement said he had six thousand euros in a

Livret

, a tax-free account set up by the state to encourage saving, and just over eight hundred in his current account. He’d been getting a pension of four hundred euros a month. There was no phone to be seen and no address book. A dusty shotgun hung on the wall and a well-used fishing rod stood in the corner. The house key hung on a hook beside the door. Left alone with the corpse until the hearse came, Bruno thoughtold Murcoing did not have much to show for a life of hard work and patriotism.

He wrote out a receipt for the gun, the box and its contents and left it in the drawer. Beside the TV set he saw a well-used wallet. Inside were a

carte d’identité

and the

carte vitale

that gave access to the health service, but no credit cards and no cash. Joséphine would have seen to that. There were three small photos, one a portrait of a handsome young man and two more with the same young man with an arm around the shoulders of the elderly Murcoing at what looked like a family gathering. That must be Paul, the favourite grandson, who was supposed to arrive. Bruno left a note for him on the table, along with his business card and mobile number, asking Paul to get in touch about the funeral and saying he’d taken the gun, the box and banknotes to his office in the

Mairie

for safe keeping.

As the hearse was arriving, Bruno’s mobile phone rang and a sultry voice said: ‘I have something for you.’ The Mayor’s secretary was incapable of saying even

Bonjour

without some hint of coquetry. ‘It’s a message from some foreigner’s cleaning woman on the road out to Rouffignac. She thinks there’s been a burglary.’

2

Bruno sighed as he set out for the site of the burglary. It was the third this month, targeting isolated houses owned by foreigners who usually came to France only in the summer. The first two families, one Dutch and one English, had been down for the Easter holidays and found their homes almost surgically robbed. Rugs, paintings, silver and antique furniture had all disappeared. The usual burglars’ loot of TV sets and stereos had been ignored and the thieves had evidently been professionals. No fingerprints were found and little sign of a break-in. Casual inspection might never have known a burglary had happened. Each of the houses had an alarm system, but one that used the telephone to alert a central switchboard, since the houses were too deep in the country for an alarm to be heard. The telephone wires had been cut.

To Bruno’s irritation, the Gendarmes had made a cursory inspection, shrugged their shoulders and left him to write a report for the insurance claim. He understood their thinking. Individual burglaries were almost never solved. The Gendarmes preferred to wait until they had a clear lead to one of the region’s fences and offer him a deal: a light

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher