![The Ritual]()

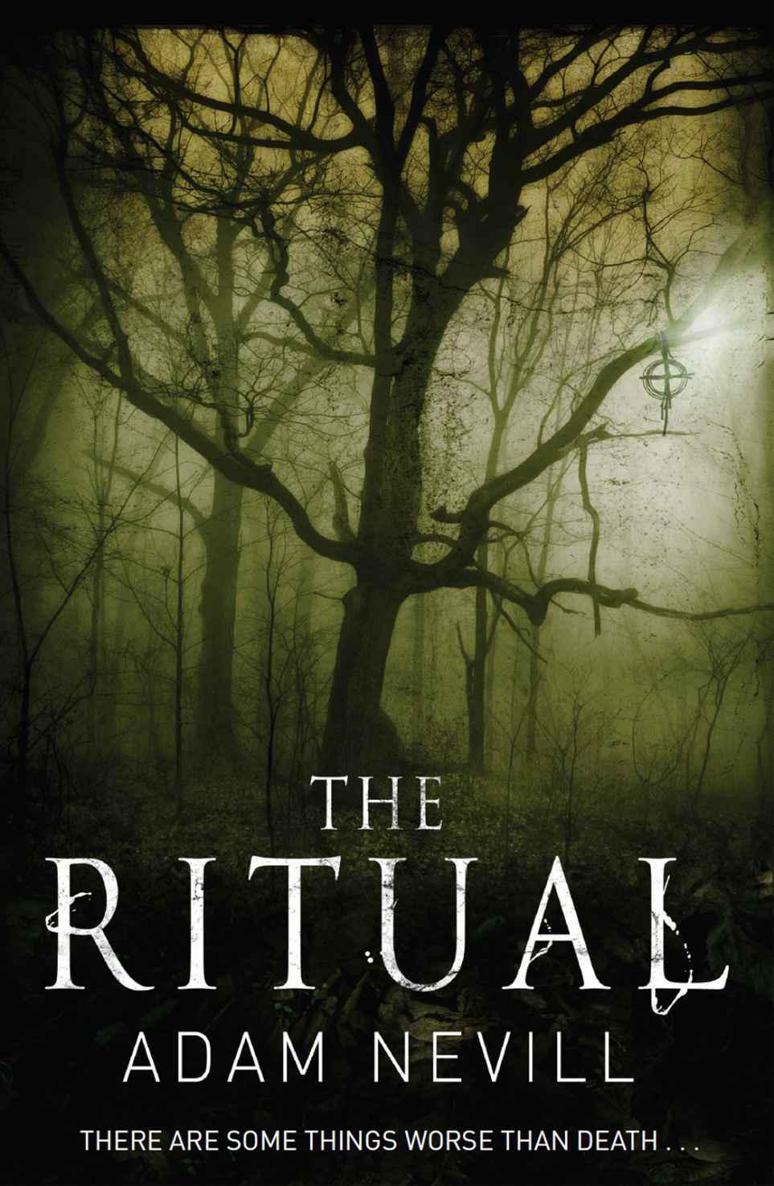

The Ritual

in the trees. An account had to be settled. For

them. He’d do anything for them now.

Why had the old woman not called it home to clean out her trespassers? Luke closed his eyes. His skin shivered. His head hurt as it wondered. There was no one to tell him anything. Not

out here. He just guessed and flinched like a small animal.

Because of the rifle. And sheath knives. Because it could be hurt. She was protecting it. Her mother. And protecting the old family upstairs. It required an inside job and he was

the man on the inside. Maybe.

But he did know that some species should become extinct. Luke opened his eyes.

Moder ’ s rule and her pitiful congregation had to end. She was an isolated God; the last black goat of the woods. What he guessed was her youngest and most presentable

daughter did her best to keep it all going up here. Maybe she was the girl left behind to look after mother. He did not know; he was guessing again. But it just all needed to stop. No more sons and

fathers and friends should hang from trees. Not that, ever.

Luke walked back to the house; every muscle and sinew ached from a bruising so deep he doubted he could ever be fixed. The horizon of treetops juddered in his vision. Somehow the sky was all

white now too, but he was grateful for the rain. It came down cold and hard. Was never far away up here. Just changed places with the snow. Over and over, forever.

He looked at Fenris. Reached down, gripped the sticky handle of the Swiss Army knife and yanked it out. Fenris sat up, head lolling, like Luke was leading him by a hand, then dropped back down

to the blood and the soil. Luke stabbed the blade into the turf twice to clean it.

On the porch, he put down the rifle and the knife and took off the little white dress. Dropped it over Loki’s terrible face. But left the crown of dead flowers on his head; it seemed to be

holding his thoughts together. And then he looked down the hallway to the staircase.

SIXTY-SEVEN

Through the door at the end of the corridor on the first storey, and up into the attic he went on feet so slow and clumsy they must have all heard him coming. Up there, in the

warm dusty timeless darkness, they knew he was coming for them.

And into the lightless place at the top of the house, he crept and fumbled about, naked and bloodied as a newborn. He had no light; couldn’t get it together enough downstairs to find an

oil lantern and matches. But he went on memory to the places where he remembered the little figures to be sitting. And now he was up there, he found they were all too old and too weak to do

anything but mutter.

The rain struck the roof and was amplified inside the attic space. Still, he could hear them all about him. Their voices were rustles, sometimes scratchy like the voices in old radios dimmed to

a murmur. And they were not laughing now. They sounded confused, like elderly people who had awoken in beds and forgotten where they were.

He went in low, head down, ears cocked to their sounds. At the far end of the room, he knelt down. Laid the rifle upon the floor. Then fumbled his hands around the two little chairs, patting his

shaking hands over their robes, dry as old bread, then over brittle limbs no thicker than woodwind instruments, until he found the first small head.

‘You killed them amongst the stones,’ he whispered. ‘Yes, you showed me. Carried them out in wagons to die.’

He placed his finger atop the slowly moving skull, raised the knife up high, and then brought the blade down.

Through it went, through skin no stiffer than yellowing paper, and through an avian skull thin as eggshell, and into what remained of a living organ. Old magic may have kept it living, but new

steel ended its long and miserable existence; a life that may well have begun when those great trees out there were mere saplings.

The other seated figure rustled in the darkness and tried to bite his fingers. He heard its dry jaw clacking.

‘I saw your old house. I was there. You used to string them up over a basin. You showed me. Did you suckle your God on blood?’

The second figure was a woman, he sensed, though it was pitch-black in the attic, and they were so old when he had first seen them he could not really be sure. But he found himself amazed at

just how accurate his instincts could be when he had nothing else to go on.

When his fingers found her in the dark, he heard her cartilage beak creak open again, then felt the snap of dry gums upon a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher