![The Six Rules of Maybe]()

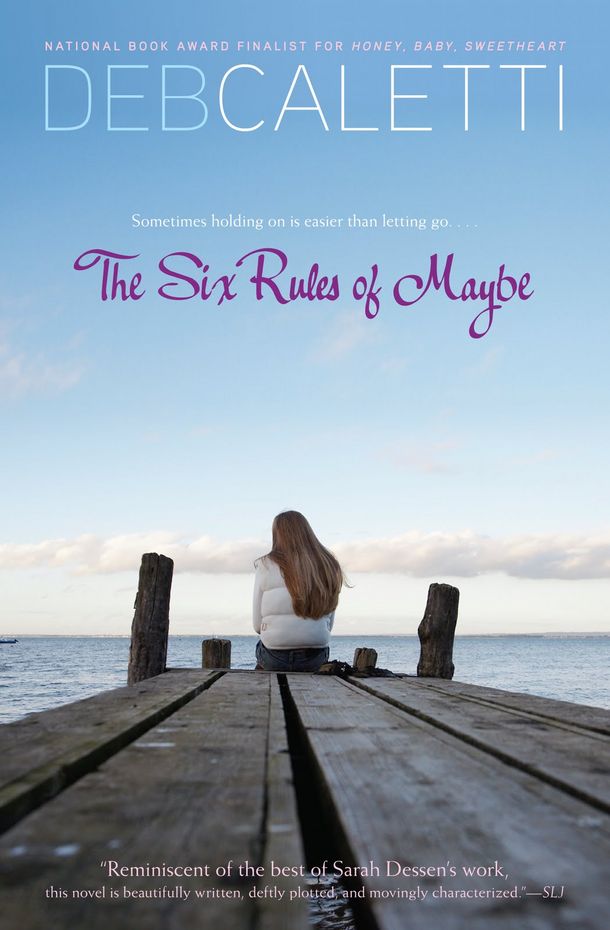

The Six Rules of Maybe

flushed.

“Millions of people received this same letter, Mrs. Martinelli.Millions. Some guy with a creepy mustache and no job wrote it in his mother’s basement.”

“Mr. Martinelli and I love cocoa in the evenings,” she said.

“Trust me,” I said.

She stared hard at me with those big eyes. “The Ivory Coast,” she said. The words managed to be both wistful and full of adventure.

“His mother’s basement,” I said.

She sighed dramatically as if there were things I’d never understand. She made her way back into her own yard, but not before she snatched the letter back with a little bit of nastiness. Her butt was big and bumpy in those stretchy pants, but still she held that paper as if it were somehow breakable. The way you hold precious things, or should hold precious things.

“Uh-oh,” Hayden said as he locked the door of the truck.

“I know.”

“I always wondered how those guys actually made any money,” he said.

“There you go.”

He came around the other side of the truck and stopped for a second, set his hand on my arm. “Scarlet.”

Some things had the right amount of weight. A quilt as you slept, carefully chosen words, fingertips.

“I really want to thank you. It’s a little weird for me here. You know—all of it. What’s going on, a new place, the whole deal. But you made it great today, and I really appreciate that.”

His eyes were warm and brown as coffee. I looked at them for a long while and he looked back. I felt something from him that you don’t feel very often. I guess it was sincerity.

“No problem, Hayden,” I said.

He let my arm go. He went inside to find Juliet. But I could still feel his touch there on my skin, lingering for a moment before fleeing, the way a good dream does, just as you wake.

Chapter Six

Y ou two got sunburned,” Juliet said at dinner. Juliet was in a bad mood, and I remembered then what Juliet in a bad mood looked like. Her temper rolled in, clouds over sky, first hazy and meandering and then dark and full and fixed. Juliet’s bad moods were irritation and dissatisfaction looking for a purpose. In other people, in me, irritation needed something to grab on to or else it just faded away with a cold drink or a nap or someone else’s patience. But Juliet seemed to like the thrilling ride from irritation to anger; she searched around for a reason to lose her temper until she found one.

It might have even felt a little good if our mutual sunburn had been what had made her mad. But I could never be a threat to Juliet. I was sure of that. Juliet held men in the palm of her hand. I had no magic tricks or power; I was only my plain old self and didn’t know how to be different than that.

I knew Juliet, anyway. The accumulation of small things thattogether make you momentarily hate your life and everyone in it could send her fuming—not finding pants that fit and then spilling her lemonade, or a long, hot day in the car with Mom who never seemed to notice when the light turned green. Juliet had a way too of putting things and people in the space between herself and what was true. If she’d had a fight with Buddy Wilkes, it was me whom she yelled at, and if our mother had upset her, Buddy himself might be the one to get her frosty words. I wondered if Hayden knew this about her yet. It was something a husband ought to know.

“It was a sunny day,” Hayden said. It sounded like an apology, and Hayden shouldn’t have given that. Not just for the obvious reasons but for a bigger one—Buddy Wilkes never took her crap.

“Must be nice to have a day off work,” Dean Neuhaus said. Mom had invited him for dinner. He sat at the end of the table in his pressed pants and pressed shirt, his tie still tight against his throat, his brown hair cut straight across the back of his neck. It was the kind of hair that said you followed the rules.

Dean had sort of been forgotten down there at the end of the table, with his prim, righteous mouth and expensive watch and leather shoes, and Dean Neuhaus didn’t like to be forgotten. One of the things I hated most about Dean was how he’d hint at his moral superiority while at the same time pointing out how humble he was. To Dean Neuhaus, everything was a sign of his moral superiority, from the way he loaded the dishwasher to how manicured his fingernails were. Dean Neuhaus had come here from London, and he managed to make our entire country inferior to his too—our grossly abundant restaurant

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher