![The Tortilla Curtain]()

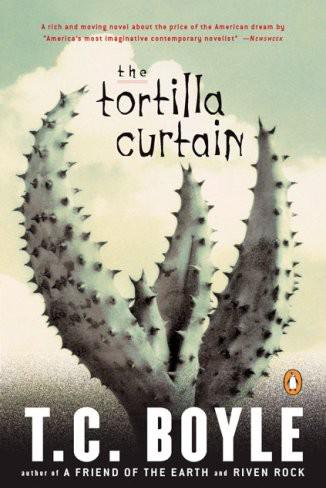

The Tortilla Curtain

some stranger's bedroom and gone snooping through the drawers. Invisible eyes locked on him. He looked over his shoulder, darted a quick glance up and down the streambed and then peered up into the branches of the trees.

For a long moment he stood there, frozen to the spot, fighting the impulse to cross the stream, bundle the whole mess up and haul it back to the nearest trash can--that'd send a message, all right. This was intolerable. A desecration. Worse than graffiti, worse than anything. Wasn't it enough that they'd degraded the better part of the planet, paved over the land and saturated the landfills till they'd created whole new cordilleras of garbage? There was plastic in the guts of Arctic seals, methanol in the veins of the poisoned condor spread out like a collapsed parasol in the Sespe hills. There was no end to it.

He looked down at his hands and saw that they were shaking. He tried to calm himself. He was no vigilante. It wasn't his place to enforce the law, no matter how flagrant the abuse--that was what he paid taxes for, wasn't it? Why let a thing like this ruin his day? He'd take his hike, that's what he'd do, put miles between him and this sordid little camp, this shithouse in the woods, and then, when he got back home, he'd call the Sheriff's Department. Let them handle it. At night, preferably, when whoever had created this unholy mess was sunk to their elbows in it, nodding over their dope and their cheap wine. The image of his Mexican rose up yet again, but this time it was no more than a flicker, and he fought it down. Then he turned and moved off up the stream.

It was rough going, clambering over boulders and through battlements of winter-run brush, but the air was clean and cool and as the walls of the canyon grew higher around him the sound of the road faded away and the music of running water took over. Bushtits flickered in the trees, a flycatcher shot up the gap of the canyon, gilded in light. By the time he'd gone a hundred yards upstream, he'd forgotten all about the sleeping bags in the dirt and the sad tarnished state of the world. This was nature, pure and unalloyed. This was what he'd come for.

He was making his way through a stand of reeds, trying to keep his feet dry and watching for the tracks of raccoon, skunk and coyote in the mud, when the image of those sleeping bags came back to him with the force of a blow: _voices,__ he heard voices up ahead. He froze, as alert suddenly as any stalking beast. He'd never encountered another human being down here, never, and the thought of seeing anyone was enough to spoil his pleasure in the day, but this was something else altogether, something desperate, dangerous even. The sleeping bags behind him, the voices ahead: these were transients, bums, criminals, and there was no law here.

Two voices, point/counterpoint. He couldn't make out the words, only the timbre. One was like the high rasp of a saw cutting through a log, on and on till the pieces dropped away, and then the second voice joined in, pitched low, abrupt and arrhythmic.

Some hikers carried guns. Delaney had heard of robberies on the Backbone Trail, of physical violence, assault, rape. The four-wheel-drive faction came up into the hills to shoot off their weapons, gang members annihilated rocks, bottles and trees with their assault rifles. The city was here, now, crouched in the ravine. Delaney didn't know what to do--slink away like some wounded animal and give up possession of the place forever? Or challenge them, assert his rights? But maybe he was making too much of it. Maybe they were hikers, day-trippers, maybe they were only teenagers skipping school.

And then he remembered the girl from the birding class he'd taken out of boredom. It was just after he'd got to California, before he met Kyra. He couldn't recall her name now, but he could see her, bent over the plates in Clarke's _An Introduction to Southern California Birds__ or squinting into the glow of the slide projector in the darkened room. She was young, early twenties, with thin black hair parted in the middle and a pleasing kind of bulkiness to her, to the way she moved her shoulders and walked squarely from the anchors of her heels. And he remembered her cheeks--the cheeks of an Eskimo, of a baby, of Alfred Hitchcock staring dourly from the screen, cheeks that gave her face a freshness and naivete that made her look even younger than she was. Delaney was thirty-nine. He asked her out for a sandwich

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher