![The Tortilla Curtain]()

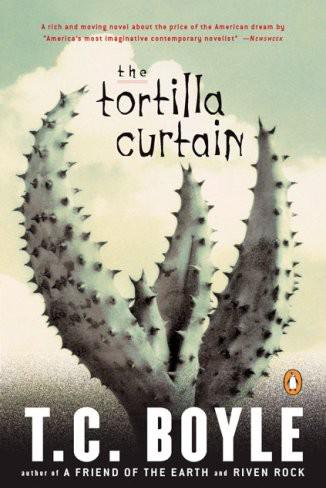

The Tortilla Curtain

running down a pair of short dark men stationed at the entrance. The men didn't look alarmed, only hopeful.

This was not a good situation. There were too many of them here and that was the sort of thing that scared buyers away from the area. Not that this stretch of the boulevard--single- and double-story older commercial buildings--was exactly her cup of tea, but there were homes five blocks from here that would go for four and five hundred thousand even now. She pulled into a space in front of the store and found an excuse to go in--she could use a package of gum, a Diet Coke maybe. None of the men dared approach her in the lot--the 7-Eleven manager would have seen to that--but they all watched her as she stepped out of the car, and their eyes were wistful, proud, indifferent. They'd take on another look if she crossed the lot.

There were two women behind the counter, both Asian, both young. They smiled at Kyra when she came in the door, kept smiling as she went back to the cooler, selected her Diet Coke and made her way back to the counter. They smiled as she selected her gum. “Find everything?” the shorter of the two asked.

“Yes,” Kyra said. “Thank you.” And this gave her her opening. “There seem to be a lot of men out there on the sidewalk--more than usual, no?”

The shorter girl--she seemed to be in charge--shrugged. “No more, no less.”

“Bad for business, no?” Kyra said, falling into the rhythm of the girl's fractured English.

Another shrug. “Not bad, not good.”

Kyra thanked her and stepped back out into the heat. She was about to slip into the air-conditioned envelope of the car and be on her way, when she suddenly swung round and crossed the lot to where the men were gathered. Now the looks were different--all the men stared at her, some boldly, some furtively. If this were Tijuana they'd be grabbing for her, making lewd comments, jeering and whistling, but here they didn't dare, here they wanted to be conspicuous only to the right people, the people who needed cheap labor for the day, the afternoon, the hour. She imagined them trading apocryphal stories of the beautiful gringa who selected the best-built man for a special kind of work, and tried to keep a neutral look on her face.

She passed by the first group, and then turned onto the sidewalk, her gaze fixed on the row of cheap apartments that backed up onto the commercial strip of the boulevard and faced out on the dense growth of pepper trees that screened the freeway from view. The apartments were seedy and getting seedier, she could see that from here--open doors, dark men identical to those crowding the sidewalk peering out at her, the antediluvian swimming pool gone dry, paint blistered and pissed over with graffiti. She stopped in the middle of the block, overwhelmed with anger and disgust and a kind of sinking despair. She didn't see things the way Delaney did--he was from the East Coast, he didn't understand, he hadn't lived with it all his life. Somebody had to do something about these people--they were ubiquitous, prolific as rabbits, and they were death for business.

She was on her way back to the car, thinking she'd drive Mike Bender by here tomorrow and see if he couldn't exert some pressure in the right places, call the INS out here, get the police to crack down, something, anything. In an ironic way, the invasion from the South had been good for business to this point because it had driven the entire white middle class out of Los Angeles proper and into the areas she specialized in: Calabasas, Topanga, Arroyo Blanco. She still sold houses in Woodland Hills--that's where the offices were, after all, and it was still considered a very desirable upper-middle-class neighborhood--but all the smart buyers had already retreated beyond the city limits. Schools, that's what it was all about. They didn't bus in the county, only in the city.

Still, this congregation was disturbing. There had to be a limit, a boundary, a cap, or they'd be in Calabasas next and then Thousand Oaks and on and on up the coast till there was no real estate left. That's what she was thinking, not in any heartless or calculating way--everybody had a right to live--but in terms of simple business sense, when she became aware that one of the men hadn't stepped aside as she crossed back into the parking lot. There was a lamppost on her left, a car parked to the right, and she had to pull up short to avoid walking right into him.

He looked up

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher