![The Tortilla Curtain]()

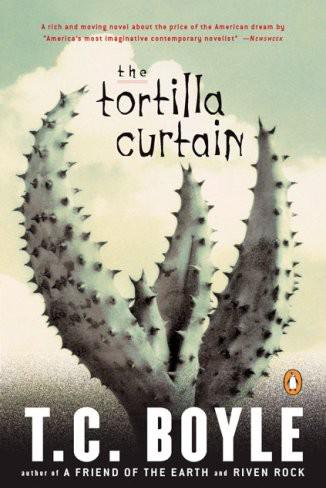

The Tortilla Curtain

Death flapping its wings over the deepest pit. Cándido had driven before--but not much, having learned on an old Peugeot in a citrus grove outside of Bakersfield on his first trip North--and he was elected to do the bulk of the driving, especially in an emergency, like this one. For sixteen hours he gripped the wheel with paralyzed hands, helpless to keep the car from skittering like a hockey puck every time he turned the wheel or hit the brakes. Finally the snow gave out, but so did the transmission, and they'd only made it as far as Wagontire, Oregon, where six _indocumentados__ piling out of the smoking wreck of a rust-eaten 1971 Buick Electra were something less than inconspicuous.

They hadn't had the hood up ten minutes, with Hilario leaning into the engine compartment in a vain attempt to fathom what had gone wrong with a machine that had already drunk up half a case of transmission oil, when the state police cruiser nosed in behind them on the shoulder of the road. The effect was to send everybody scrambling up the bank and into the woods in full flight, except for Hilario, who was still bent over the motor the last time Cándido laid eyes on him. The police officers--pale, big-shouldered men in sunglasses and wide-brimmed hats--shouted incomprehensible threats and fired off a warning shot, but Cándido and two of the other men kept on running. Cándido ran till his lungs were on fire, a mile at least, and then he collapsed in a gully outside of a farmhouse. His friends were nowhere in sight. He was terrified and he was lost. It began to rain.

He couldn't have been more at a loss if he'd been dropped down on another planet. He had money--nearly four hundred dollars sewed into the cuff of his trousers--and the first thing he thought of was the bus. But where was the bus? Where was the station and how could he hope to find it? There was no one in the entire state of Oregon who spoke Spanish. And worse: he wasn't even sure, in terms of geography, where exactly Oregon was and what relation it bore to California, Baja and the rest of Mexico. He crouched down in the ditch, looking wistfully across the field to the farmhouse, as the day closed into night and the rain turned to sleet. He had a strip of jerky in his pocket to chew on, and as he tore into the leathery flavorless meat with quivering jaws and aching teeth, he remembered a bit of advice his father had once given him. In times of extremity, his father said, when you're lost or hungry or in danger, _ponte pared,__ make like a wall. That is, you present a solid unbreachable surface, you show nothing, neither fear nor despair, and you protect the inner fortress of yourself from all comers. That night, cold, wet, hungry and afraid, Cándido followed his father's advice and made himself like a wall.

It did no good. He froze just the same, and his stomach shrank regardless. At daybreak, he heard dogs barking somewhere off in the distance, and at seven or so he s coán or so haw the farmer's wife emerge from the back door of the house with three pale little children, climb into one of the four cars that stood beside the barn, and make her way down a long winding drive toward the main road. The ground was covered with a pebbly gray snow, an inch deep. He watched the car--it was red, a Ford--crawl through that Arctic vista like the pointer on the bland white field of a game of chance at a village _fiesta.__ Awhile later he watched a girl of twenty or so emerge from the house, climb into one of the other cars and wind her way down the drive to the distant road. Finally, and it was only minutes later, the farmer himself appeared, a _güero__ in his forties, preternaturally tall, with the loping, patient, overworked gait of farmers everywhere. He slammed the kitchen door with an audible crack, crossed the yard and vanished through the door to the barn.

Cándido was a wall, but the wall was crumbling. He wasn't used to the North, had seen snow only twice before in his life, both times with the potatoes in Idaho, and he hated it. His jacket was thin. He was freezing to death. And so, he became a moving wall, lurching up out of the ditch, crossing under a barbed-wire fence and making his way in _huaraches__ and wet socks across the field to the barn, where he stopped, his heart turning over in his chest, and knocked at the broad plane of painted wood that formed one-half of the door through which the farmer had disappeared. He was shivering, his arms wrapped round

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher