![The Underside of Joy]()

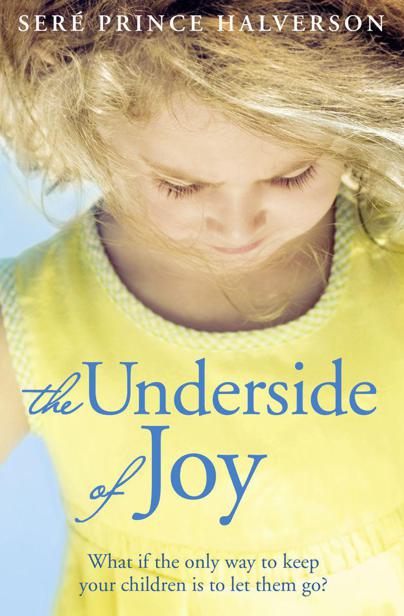

The Underside of Joy

We’re sending Daddy berries.’

‘To heaven!’ Zach yelled. ‘And someday I’m going to go to heaven to visit him! On Thomas the Tank Engine!’

‘Actually,’ Annie said, stopping to aim her grin directly at me. ‘We’re sending him Rubus fruticosus. ’ It was one of the first Latin plant names my father had taught me. And I had taught Annie. And like me, she had a knack for remembering.

Later, as we ate lunch, I told them how we were going to make the store a place to get picnic baskets and good lunches and games. I reminded them how Daddy’s grandpa had built the store, how it had been in the family, and told them how it was ours and Uncle David’s and Nonna’s and Nonno’s. That we would always remember Daddy whenever we were at the store. That now they were going to be a big part of it too, because I would need their help, and that someday it would be theirs, if they wanted it when they grew up.

‘Daddy loved picnics,’ Annie said.

‘Yes, he did.’

‘Daddy was the picnic CRUSADER !’ Zach said, bolting up, while I reached out to keep a couple of cups from spilling all over our lunch spread.

‘Yes, he was.’

‘Mommy?’ he asked. ‘I want to be a picnic crusader too. Can I use this picnic blanket for a cape?’

‘No, bud. You can’t.’

‘Because our stuff is all over it?’

‘That’s exactly why. You are one smart crusader.’

‘Even without my cape?’

‘Even without your cape.’

The overhaul of Capozzi’s Market began immediately. The whole family joined us – all the aunts and uncles and cousins. The next weekend, close to everyone in Elbow turned out. I hauled away boxes of canned goods and disassembled shelving until my arms and legs and back throbbed, and then woke up the next day and did it again. Frank helped a crew working on a greenhouse-type addition at the back of the store for the winter months, when the rain would deter even the most diehard picnickers.

Frank told me he was looking forward to having his coffee by the fire in the mornings. We stared at each other for a long moment, his eyes saying how much he missed Joe. I hadn’t seen him enough since Joe died; he’d come by a few times, but it had just felt awkward and sad, both of us lonely for the same person, neither of us able to be that person for the other. Lizzie even stopped by with a big cooler full of drinks and snacks. She nodded in my direction but talked to David, not me, then slipped back out, waving to and hugging one person after another. I wondered if she’d talked to Paige, if they’d mocked my What are your intentions? question.

But Paige had called Annie only a few times since our conversation, and I hoped that she might be pulling back a bit. At least I kept telling myself that she was.

At first, the fact that we were taking apart Joe’s store lay thick and cold as the morning fog, and we moved hesitantly, quietly. Me wondering: Why didn’t we do this a long time ago, together? Why did Joe have to die before we fixed this? But the mood lightened when I began to feel Joe cheering us on. I saw what it must have been like for him to feel it slipping away, that it had begun to represent failure and that perhaps from wherever he was now, he might be relieved. Maybe even proud.

I was taking down the family photographs when Joe Sr came up and said, ‘Where are you going to put those?’

‘I’m not sure, but definitely in a prominent place. Where do you think they should go?’

He took one from me. It was an old black-and-white. Someone had written in black in the corner, Capozzi’s Market, 1942. Grandma Rosemary stood with two boys in front of the store.

‘Which one was you?’ I asked.

He pointed to the youngest, a boy of about seven or eight wearing a tilted cap and a smudge on his face. The other boy looked like a teenager. ‘I didn’t know you had an older brother.’

He nodded. ‘He died in the war. Fighting for this country.’

‘I’m sorry. That must have been hard.’ He nodded again, still staring at the photograph. ‘Hey, where’s Grandpa Sergio? Is he taking the picture?’

He shook his head. ‘No. He gave his son to fight against Italy, but he wasn’t a citizen yet, so . . .’

I held up another photo, also dated 1942. ‘He’s not in this one, either.’

‘No, honey. My papa wasn’t around when those pictures were taken . . . Like I’ve said, he had to go away for a while.’ These photos were taken when he was in the camps. I knew

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher