![The Underside of Joy]()

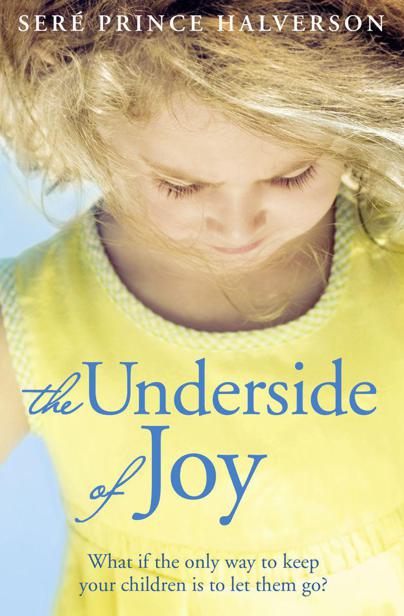

The Underside of Joy

getting his work done.

The door chimed and David and Gil came in carrying boxes and bags with Annie and Zach dragging in metal buckets of kindling to set by the woodstove. Marcella followed with armfuls of hydrangeas. Lucy brought more wine.

I said, ‘Lucy, I’ve got to track down Clem Silver. I know he lives up in the shadies, but I don’t know where exactly.’

‘Just follow Spiral Road all the way, past the sign that says beware of artist. It’s the last house, about a quarter mile past what you’ll think is the last house.’ She pointed to the door. ‘You’re doing great. I’ve got the kids and everything here covered. Go.’

‘Are you sure? You’re dealing with harvest.’

‘Crush will go on without me. And I needed a break from jeans and boots and purple stains. Go. And, El? Take your time. Take a break. Please.’

Lucy straightened her cream velvet hat, turned around with a swirl of her long paisley skirt, and called Annie and Zach to help with the tablecloths.

I ducked out the front door, glad to get away for a walk. I headed up the street, passed the tiny postage stamp-size post office and the two restaurants and the Elbow Inn, passed the Nardinis’ house and the Longobardis’ and the McCants’, then crossed the busier road that divided the town of Elbow from the forest.

I walked the steep single-lane Spiral Road, which did, indeed, spiral the hill. The founders of this town had certainly been literal with some of their names. But it was the Southern Pomo Indians who had first referred to this area as the Shady Place. They would set up only temporary camps in the dark redwoods; they preferred to live in the sun-drenched oak-studded hills. The Kashaya Pomo even called themselves ‘the People from the Top of the Land’, as if to boast, ‘We live in the nice, sunny neighbourhood.’

Then the whites started moving in to lumber. After they built the railroad, San Franciscans began taking the train up to fish and play along the river. Some of them built summer homes in the forest, but few lived there yearlong, and that was still true. A lot of people who had houses in the shadies fled to places like Palm Springs for the winter.

I kept walking, taking the hairpin turns and pausing now and then to catch my breath. The houses sat farther and farther apart, the higher I went.

Finally, ahead, a sign that said, sure enough, beware of artist. Farther up I could see a house, but it was not the house I’d expected, not that of a man who rarely cut his hair or his fingernails.

This was a house that had been built with care and concern for every planed piece of wood, for every river rock fitted perfectly in the massive chimney and foundation. It was positioned so that it was never going anywhere. The hill could slide in an avalanche of mud and trunks, but the destruction would likely divide into two forks to go around this house, leaving it untouched. The front door held panes of stained glass and greened copper detailing and was flanked with pots of tiny white flowers trimmed in red, called lipstick salvia. A row of different sized and shaped chimes seemed to stir in their sleep, then settled back into the quiet. I knocked and set off waves of barking from somewhere deep inside.

A raspy voice said, ‘Petunia! Pipe down, girl. No need to get your britches in a bunch, Jerry.’ He opened the door and took a long look at me. He had on an old Cal sweatshirt, covered in paint stains, a pair of grey baggy sweats. His ponytail was draped over his shoulder and lay like a skinny mink stole down his chest. ‘Oh! Ella Beene! Come in, come in.’ He turned and scuffed down the hallway in lambskin slippers. The dogs, who had stopped barking, took an inventory of me too, then, seemingly unimpressed, turned to follow Clem. I stepped inside.

It was warm and golden with lamplight. ‘Wow,’ I said. ‘I love your place.’

He turned, pleased. ‘Why, thank you. I like it too.’

‘It’s beautiful here in the forest.’

He nodded, kept nodding. ‘Yes, yes! Makes you understand how this was all under the sea three hundred million years ago.’ He smiled. ‘Wait, I should offer you tea. Or coffee?’

I opted for tea, and while he fixed it, he talked. ‘People think I live up here to get away from the river, because of the flooding and what I went through as a child.’

‘What was that?’ I asked.

‘Oh . . . I forget you’re not from around here . . . It’s an old story. Old, old story.

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher