![Three Seconds]()

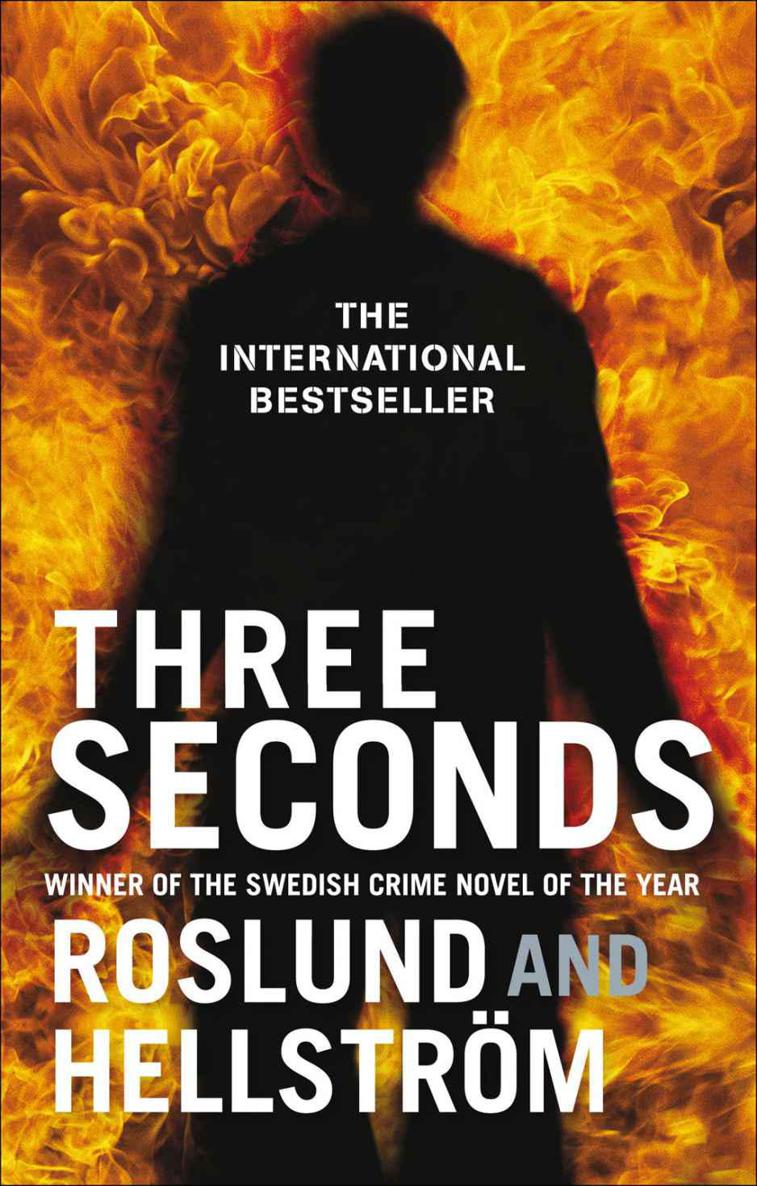

Three Seconds

freezer before being put in the fridge and suddenly the evening had disappeared without him having called.

Thirty-three hours left.

He opened the front door that was locked. No TV humming in the sitting room, no light over the round table in the kitchen, no radio from the study and the slow P1 talk shows that she liked so much. He had come home to a hostile house, to reactions that he couldn’t control and that scared him.

Piet Hoffmann swallowed the feeling of being so totally fucking alone.

He had actually always been lonely, never had many friends as he dropped them one by one because he didn’t understand the point, didn’t have many relatives as he lost touch with those who hadn’t dropped him first, but this was a different loneliness, one that he hadn’t chosen himself.

He turned the light on in the kitchen. The table was empty, no blobs of jam and crumbs from

just one more biscuit

, it had been wiped in circles until everything had been cleaned off. If he leant forward he could even see the stripes from a J-cloth on the shiny pine surface. They had sat there eating supper, just a few hours ago. And she had made sure that they finished their meals, he had not been there and wouldn’t be part of it later either.

The vase was in the cupboard over the sink.

Twenty-five red tulips, he straightened the card, I love you, they would stand in the middle of the table where the card was visible.

He tried to put his feet down as quietly as possible on the stairs, but every tread creaked in warning and the ears that were listening would know he was near. He was frightened, not of the anger he would confront any minute now, but of the consequences.

She wasn’t there.

He stood in the doorway and looked into an empty room. The bedspread was still on the bed and hadn’t been touched. He carried on to Hugo’s room and coughs from a throat that was only five years old and swollen. She wasn’t there either.

One more room. He ran.

She was lying on the short, narrow bed snuggled close to their youngest son. Under the blanket, curled up. But she wasn’t asleep, her breathing wasn’t that regular.

‘How are they?’

She didn’t look at him.

‘Have they still got a temperature?’

She didn’t answer.

‘I’m so sorry, I couldn’t get away. I should have called, I know, I know that I should have.’

Her silence. It was worse than everything else. He preferred open conflict.

‘I’ll look after them tomorrow. The whole day. You know that.’

That bloody silence.

‘I love you.’

The stairs didn’t creak as much when he went down. His jacket was hanging on the coat rack in the hall. He locked the front door behind him.

__________

Thirty-two hours and thirty minutes left. He wouldn’t sleep. Not tonight. Not tomorrow night. He would have plenty of time to do that later, locked up in five square metres for two weeks on remand, on a bunk with no TV and no newspapers and no visitors, he could lie down then and close out all this shit.

__________

Piet Hoffmann sat in the car while the rest of the street went to sleep. He often did this, counted slowly to sixty and felt his body relaxing limb by limb.

Tomorrow.

He’d tell her everything tomorrow.

The windows in the neighbouring houses that shared his suburban life went black one by one. The blue light of a TV still shone upstairs at the Samuelssons’ and the Sundells’; a light that changed from yellow to red in the Nymans’ cellar window, where he knew one of their teenage sons had a room. Otherwise, night had fallen. One last look at the house and the garden he could touch if he wound down the window and stuck out his hand, he was sure of it, which were now blanketed in silence and blackness, not even the small lights in the sitting room were on.

He would tell her everything tomorrow.

The car crept along the small streets as he made two phone calls; the first about a meeting at midnight at number two, the second about another meeting later at Danviksberget.

He wasn’t in a rush any more. An hour to hang around. He drove towards the city, to Södermalm and the area round Hornstull, where he had lived for so many years when it was still a rundown part of town that the city suits sneered at if they happened to stray there. He parked down by the waterfront on Bergsunds Strand, by the beautiful old wooden bath house that some crazy people had fought so hard to pull down a few years back and was now a hidden gem in this hip

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher