![Three Seconds]()

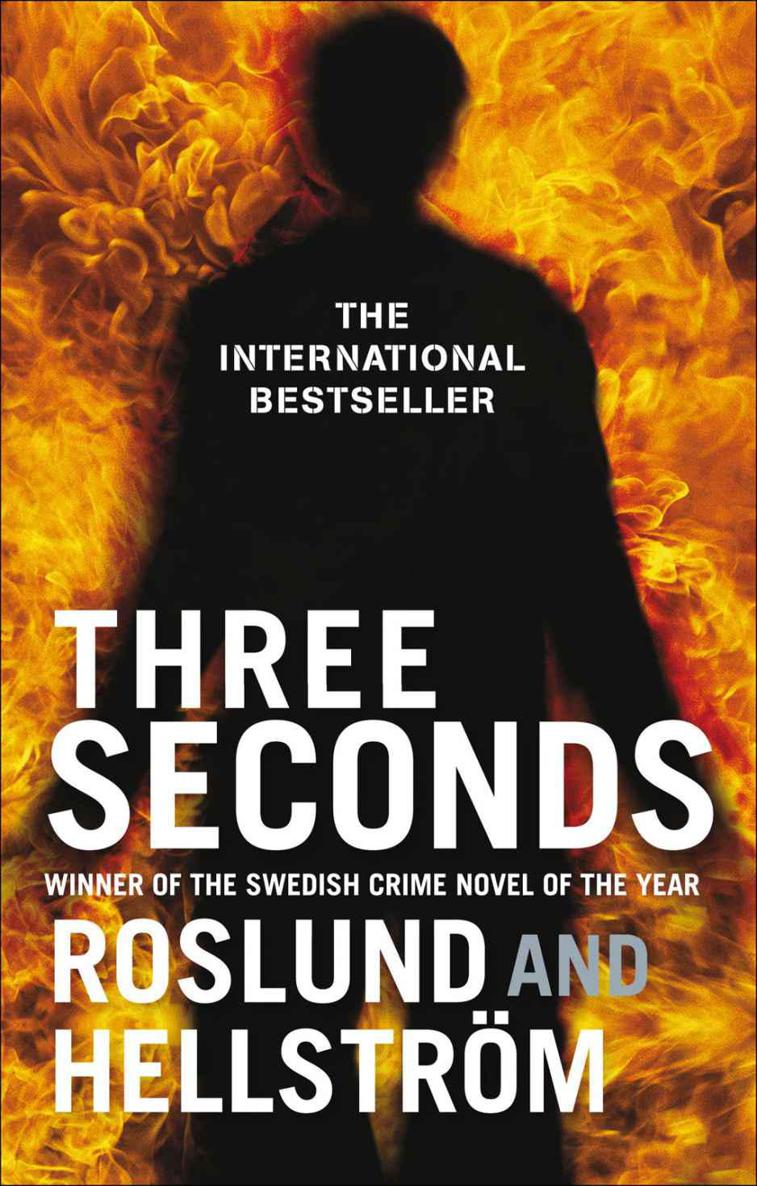

Three Seconds

machine that stood in the bedroom and seemed like a huge bit of furniture to aseven-year-old. First, with great care, he undid the screw on one side of the wooden butt, put it down on the white surface of the worktop so that he could see it – he mustn’t lose it. The next screw was on the other side of the butt and closer to the hammer. Then with the point of the screwdriver against the pin in the middle of the revolver, he tapped it lightly a couple of times until it fell out and the toothpick-sized gun broke up into six separate parts: the two butt sides, the revolver frame with the barrel and cylinder pivot and trigger, the cylinder with six bullets, the barrel protector and a part of the frame that didn’t have a name. He put each piece in a plastic bag and carried them out with eighteen metres of pentyl fuse and four centilitres of thinly packaged nitroglycerine, all of which was then placed on top of nine hundred and fifty thousand kronor in a brown bag behind the spare tyre in the boot of the car.

__________

Piet Hoffmann had sat on one of the kitchen chairs and watched the light force back the night. He had been waiting for her for hours, and now he heard her heavy tread on the wooden stairs, foot flat down on the surface in the way that she always did when she hadn’t had enough sleep. He often listened to people’s steps – they clearly reflected what was going on inside and it was always easier to work out how someone was feeling by closing his eyes when he or she approached.

‘Good morning.’

She hadn’t seen him and she jumped when he spoke.

‘Hi.’

The coffee was already made, so he poured in just the amount of milk she liked in the morning. He carried the cup over to the beautiful and tousled and sleepy woman in a dressing gown, and she took it, such tired eyes, she had been furious for half the night and then slept in a bed with a feverish child for the other half.

‘You haven’t slept at all.’

She wasn’t irritated, her voice didn’t sound it, she was just tired.

‘Just worked out that way.’

He put some bread, butter and cheese on the table.

‘Their temperatures?’

‘They’ve gone down. For the moment. A few more days at home, maybe just two.’

More footsteps, much lighter, feet that were bright from the moment they left the bed and touched the floor. Hugo was oldest but still woke up first. Piet went over to him, picked him up and kissed and squeezed his soft cheeks.

‘You’re prickly.’

‘I haven’t shaved yet.’

‘You’re more prickly than normal.’

Bowls, spoons, glasses. They all sat down, Rasmus’s chair still empty, but they would leave him to sleep as long as he needed to.

‘I’ll take them today.’

She had expected him to say that. But it was hard. Because it wasn’t true.

‘The whole day.’

The set table. Not so long ago, nitroglycerine had lain there beside some pentyl fuse and a loaded gun. Now it was laden with porridge and yoghurt and crispbread. The cornflakes crunched noisily and some orange juice was spilt on the floor. They ate their breakfast as they usually did until Hugo banged his spoon down on the table.

‘Why are you angry with each other?’

Piet exchanged glances with Zofia.

‘We’re not angry.’

He had turned to his oldest son as he spoke and instantly realised that this five-year-old was not going to be satisfied with a platitude and therefore decided to hold his challenging eyes.

‘Why are you lying? I can tell. You

are

angry.’

Piet and Zofia looked at each other again and then she decided to answer.

‘We

were

angry. But we’re not any more.’

Piet Hoffmann looked at his son with gratitude and felt his shoulders dropping. He had been so tense, longing to hear those words, but he hadn’t dared ask the question himself.

‘Good. No one’s angry. Then I want more bread and more cornflakes.’

His five-year-old hands poured more cereal on what was already in his bowl and put some cheese on another slice of bread which then lay next to the first one that hadn’t even been started yet. His parents chose not to say anything, this morning he was allowed to do as he pleased. He was wiser than them right now.

__________

He sat on the wooden step by the front door. She had just left. And he still hadn’t said what he needed to say, it just hadn’t worked out that way. Tonight. Tonight he would tell her. About everything.

He’d given Hugo and Rasmus a dose of Calpol as soon as her back

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher