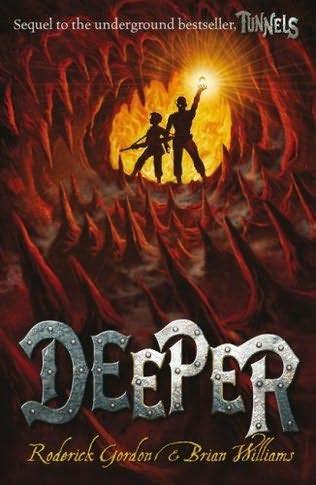

![Tunnels 02, Deeper]()

Tunnels 02, Deeper

ideal breeding ground."

Mrs. Burrows contemplated making a break for the door. She wasn't going to hang around to hear this old fruitcake's prattle, and besides, she'd all but lost her appetite. The upside to this mystery pandemic was that it was very unlikely there would be any activities organized for the day, so she could get in some serious television viewing with little or no opposition to her choice of show. Even if she couldn't see much, at least she could listen to it.

"We're all suffering from this rather nasty eye infection at the moment, but it wouldn't take much for it to shuffle a couple of genes and turn into a killer." The man picked up a salt shaker and shook it over his egg. "Mark my words, one day something really nasty will appear on the horizon, and it'll cut us all down, like a scythe through corn," he announced, delicately dabbing the corners of his eyes with his handkerchief. "Then we'll go the way of the dinosaurs. And all this" -- he swept his hand expansively around the room -- "and all of us, will be a rather short and rather insignificant chapter in the history of the world."

"How very cheery. Sounds like some naff science fiction story," Mrs. Burrows said sneeringly as she rose to her feet and began to grope her way from table to table, headed for the hallway.

"It's a disagreeable but very likely scenario for our eventual demise," he replied.

This last pronouncement really got Mrs. Burrows's goat. It was bad enough that her eyes were killing her without having to listen to this claptrap. "Oh yes, so we're all doomed, are we? And how would you know?" she said scornfully. "What are you, anyway, a failed writer or something?"

"No, actually, I'm a doctor. When I'm not in here, I work at St. Edmund's -- it's a hospital -- you might have heard of it?"

"Oh," Mrs. Burrows mumbled, pausing in her flight and turning to where the man was sitting.

"Seeing -- so to speak -- as you also seem to be something of an expert, I wish I could share your faith that there's nothing to be worried about."

Feeling more than a little humbled, Mrs. Burrows remained standing where she was.

"And try not to touch your peepers, my dear -- it'll only make them worse," the man said curtly, swiveling his head to watch as two pigeons engaged in a tug-of-war over a bacon rind at the foot of the bird table.

22

For a couple of miles all that could be heard was the crunch of their feet in the dust. It was hard going for Will and Chester, trudging along with their silent captors, who yanked them roughly to their feet if either of them happened to stumble and fall. And on several occasions, the boys had been pushed and struck viciously to make them pick up the pace.

Then, without any warning, they were both drawn to a halt and their blindfolds tugged off. Blinking, the boys looked around; they were evidently still on the Great Plain, but there were no features to be seen in the illumination from the miner's light on the head of the tall man who stood before them. The glare from the light meant they couldn't see his face, but he was wearing a long jacket with a belt slung around his waist that had numerous pouches attached to it. He took something from one of these -- a light orb, which he held in his gloved palm. Then he reached above his forehead and turned off the miner's light.

He unwound a scarf from around his neck and mouth, switching his stare between the two boys as he did so. His shoulders were broad, but his face was the thing that held their attention. It was a lean face with a strong nose and one eye that glinted blue at them. The other eye had something in front of it, held in place by a band around the top of his head, like a drop-down lens.

It reminded Will of the last time he'd had his eyes tested; the optician examining him had worn a similar device. However, this version had a milky lens and, Will could have sworn, a very faint orange glow to it. He immediately assumed that the eye underneath had been damaged in some way, but then noticed a pair of twisted cables attached to the monocle's perimeter that passed around the headband and behind the man's head.

The single, uncovered eye continued to assess both of them, shrewd and quick as it darted from one to the other.

"I don't have much patience," the man began.

Will was trying to guess his age, but he could have been anything from thirty to fifty, and he had such an imposing physical presence that neither boy could fail to be

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher