![Waiting for Wednesday]()

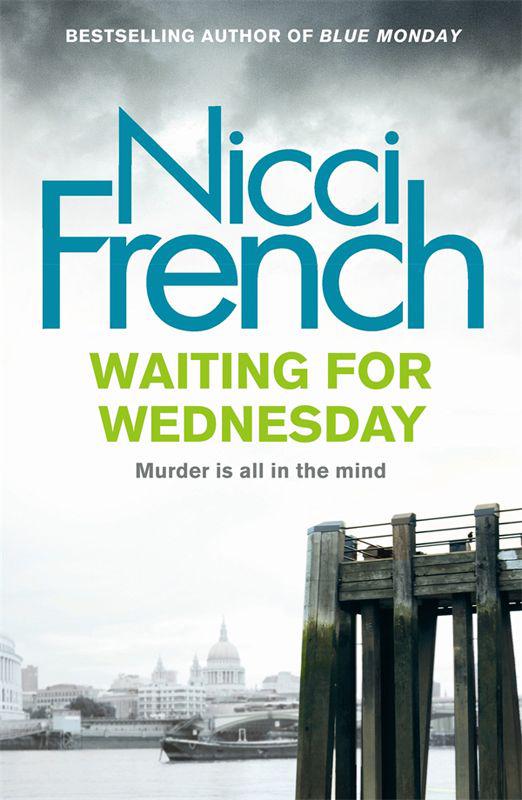

Waiting for Wednesday

instantly.’

‘Who did you think it was, before you

discovered it couldn’t be?’

‘A local druggie with a record, but it

turns out that he has a rock-solid alibi. He was caught on CCTV somewhere else at the

time of her death. He admitted to breaking in, stealing some stuff, finding her body and

fleeing the scene. We didn’t believe him, but for once in his life he was telling

the truth.’

‘So the broken window was

him?’

‘And the burglary. There was no sign

of a break-in when a neighbour came round earlier – we know Ruth Lennox must have been

already dead. Obviously the implication is that she let the killer in

herself.’

‘Someone she knew.’

‘Or someone who seemed

safe.’

‘Where did she die?’

‘In here.’ Karlsson led her into

the living room, where everything was tidy and in its proper place (cushions on the

sofa, newspapers and magazines in the rack, books lining the walls, tulips in a vase on

the mantelpiece), but a dark bloodstainstill flowered on the beige

carpet and daubs of blood decorated the near wall.

‘Violent,’ said Frieda.

‘Hal Bradshaw believes it was the work

of an extremely angry sociopath with a record of violence.’

‘And you think it’s more likely

to be the husband.’

‘That’s not a matter of

evidence, just the way of the world. The most likely person to kill a wife is her

husband. The husband, however, has a reasonably satisfactory alibi.’

Frieda looked round at him.

‘We’re taught to beware of strangers,’ she said. ‘It’s our

friends most of us should worry about.’

‘I wouldn’t go that far,’

said Karlsson.

They went through to the kitchen and Frieda

stood in the middle of the room, looking from the tidily cluttered dresser to the

drawings and photos stuck to the fridge with magnets, the book splayed open on the

table. Then, upstairs, the bedroom: a king-sized bed covered with a striped duvet, a

gilt-framed photo of Ruth and Russell on their wedding day twenty-three years ago,

several smaller-framed photos of her children at different ages, a wardrobe in which

hung dresses, skirts and shirts – nothing flamboyant, Frieda noticed, some things

obviously old but well looked-after. Shoes, flat or with small heels; one pair of black

leather boots, slightly scuffed. Drawers in which T-shirts were neatly rolled, not

folded; underwear drawer with sensible knickers and bras, 34C. A small amount of makeup

on the dressing-table, and one bottle of perfume, Chanel. A novel by her side of the

bed,

Wives and Daughters

by Elizabeth Gaskell, with a bookmark sticking out,

and under it a book about small gardens. A pair of reading glasses, folded, to one

side.

In the bathroom: a bar of unscented soap,

apple hand-wash, electric toothbrush – his and hers – and dental floss,shaving cream, razors, tweezers, a canister of deodorant, face wipes, moisturizing

face cream, two large towels and one hand towel, two matching flannels hung on the side

of the bath, with the tap in the middle, a set of scales pushed against the wall, a

medicine cabinet containing paracetamol, aspirin, plasters of various sizes, cough

medicine, out-of-date ointment for thrush, a tube of eye drops, anti-indigestion

tablets … Frieda shut the cabinet.

‘No contraceptives?’

‘That’s what Yvette asked. She

had an IUD – the Mirena coil, apparently.’

In the filing cabinet set aside for her use

in her husband’s small study, there were three folders for work, and most of the

others related to her children: academic qualifications, child benefit slips, medical

records, reports, on single pieces of paper or in small books, dating back to their

first years at primary school, certificates commemorating their ability to swim a

hundred metres, their participation in the egg-and-spoon race or the cycling proficiency

course.

In the shabby trunk beside the filing

cabinet: hundreds and hundreds of pieces of creativity the children had brought back

from school over the years. Splashy paintings in bright colours of figures with legs

attached to the wobbly circle of the head and hair sprouting like exclamation marks,

scraps of material puckered with running stitch and cross stitch and chain stitch, a

tiny home-made clock without a battery, a small box studded with over-glued sea shells,

a blue-painted clay pot, and you could still see the finger marks pressed into its

asymmetrical rim.

‘There are also several bin bags full

of old baby clothes in the loft,’ said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher