![What became of us]()

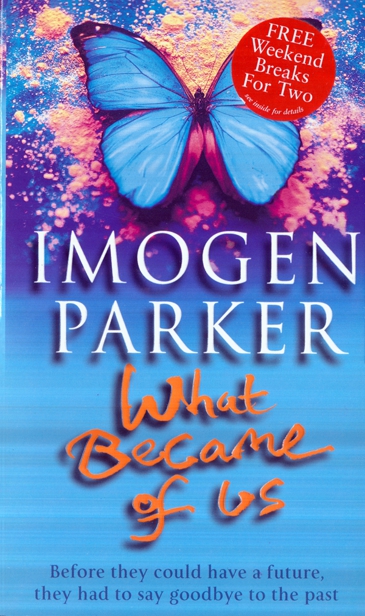

What became of us

chorus whether the production was Cabaret or the Lysistrata, except for the time when she had gone for the role of Juliet in a garden production, and been cast as the nurse.

After Oxford, she had spent several years appearing in meaningful fringe productions financed by meagre Arts Council grants to audiences of five or six, but her nearest brush with earning any money from her craft was getting into the last three for the girls in the Philadelphia advert. She made her living as a serving wench in one of London’s Tudor theme restaurants catering solely to Japanese and American tourists, where she handed out whole spit-roasted chickens on wooden platters and poured ale from earthenware jugs. The hours enabled her to go for auditions during the day. One morning a week, she went into the BBC to write gags for radio shows.

By the time she was thirty, she had just enough income to rent a dark little ground-floor flat in Shepherd’s Bush, on her own instead of sharing co-ops with other struggling actors. Seeing some of her peers making millions in the City, she was not entirely ecstatic about the hand life had dealt her, but was satisfied at least that she had not sold out as so many people seemed to have done in the Eighties. She would probably have continued like that if she hadn’t one Saturday night, in the days when comedy was still called alternative, agreed to stand in for a gag-writing friend of hers who had flu and didn’t want to lose his regular stand-up spot in a pub in Islington.

Annie was neither booed off the stage, nor greeted with any reaction other than a couple of misogyn-istic comments about her bra size which she thought she handled quite well. Afterwards, in the loo, she bumped into a fretful woman who had lost three consecutive pound coins in the tampon machine. Annie offered her a new-shaped Lil-let from the box, like a fellow smoker offering a clandestine cigarette in a smoke-free office. The woman had nipped gratefully into a cubicle and started talking to her from behind the door as if the gift of sanitary protection had made them instant friends.

‘Do you think comedy is the new rock ’n’ roll?’ the woman had called.

‘Err...’

‘Not on tonight’s showing,’ the woman continued.

‘Umm...’

‘I thought most of it was so bad,’ the woman said, making it sound as if so had at least three syllables. Jesus, it’s depressing out there...’

Annie didn’t know whether she ought to leave. The woman seemed to be taking a long time. But she decided it might be rude just to slump off. There was something curiously intimate about talking to sorneone on the other side of a toilet door.

‘…the only one I liked was the one with the observational monologue. That I could relate to. I’m just so sick of women telling jokes about periods and how men don’t understand, aren’t you?’

‘Hmm...’

‘Angie McSomething...’

‘Annie McClintock?’

Annie’s stage name, which was very close to her real name, had been an instant decision before she went on, chosen because the publican had a photo of the winning Arsenal double team from 1971 behind the bar.

‘That’s it.’

‘That was me.’

‘Oh bugger,’ said the woman in the toilet, ‘well, I blew that, didn’t I? Buy you a drink?’

With the door separating them, Annie had not known whether the offer was made in earnest. Then the woman flushed and reappeared.

‘I’m blind without my glasses,’ she explained. ‘I forget to bring them unless it’s work, although this is work too, bloody hard work sometimes.’

For a comedy producer, Annie thought later, Tessa was an incredibly disconsolate person.

She had never known whether it was her act or the tampon which had given her her lucky break, but after a couple of pints Tessa had informed her that she was looking to commission comedy from women. They got talking about their favourite sitcoms of all time, and Annie had sensed that she was on to something when her passionate championing of The Lucy Show brought the first smile of the evening to Tessa’s face. By the end of the night, she had improvised an idea for exactly the sort of American-style observational sitcom that Tessa said she was looking for, which was based on a would-be actress who earned her living as a serving wench in a theme restaurant.

‘Yes, yes, yes!’ Tessa said, getting out her Psion organizer to fix a date for Annie to come into the office, ‘it’s sort of twenty-something Cybil

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher