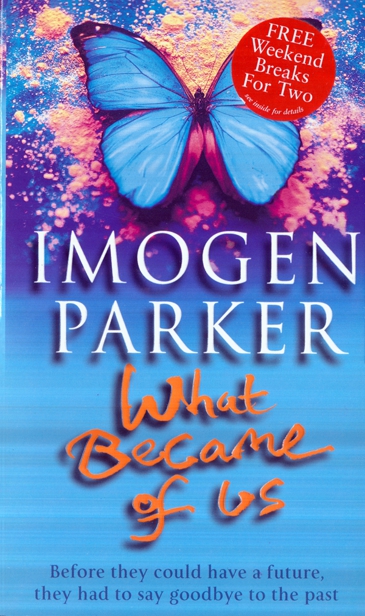

![What became of us]()

What became of us

mothering.

‘We must be getting a move on,’ he said, looking at his watch, ‘we’re going to be late.’

He and Manon walked down the garden path to the car then turned and waved. Geraldine stood in the doorway waving back. Two little faces blew kisses from the window halfway up the stairs.

‘Thank you for rescuing Lily,’ Roy said, as they pulled away.

‘I was the one who let her fall in,’ Manon replied immediately.

She was sitting in the passenger seat next to him as he drove up to the main road away from the village for the second time that day. He took his eyes off the road for a moment to look at her. Her back was stiff and she was staring ahead as if determined not to look at him.

The evening was drawing in and the quality of the light on the fields had changed from glaring to soft, from Brilliant White to Golden Amber, he thought thinking of the myriad colours of paint in the interior decoration magazines that Geraldine had started buying recently.

He wanted to say something that would make Manon smile at him as she had this afternoon when, thrown together by the spontaneous closeness of near disaster, she had let the invisible barrier between them drop for a few moments.

‘Penny once said that you always jumped at the chance to take responsibility for things that went wrong, but you would never jump at the chance to be kind to yourself,’ he ventured, and saw immediately that his words infuriated her. Nobody knew better than Manon what Penny had said.

‘Anyone would have done what I did,’ Manon retorted, opening a window as if she could not breathe in the car. If she could have climbed out and sat on the roof for the rest of the journey to avoid talking to him, he knew that she would have done that.

‘Anyone?’ he tried to inject a little lightness into the conversation, which seemed to have become much more portentous than he had imagined it could only seconds before. ‘You’ve got to be kidding. Annie would have spent thirty seconds weighing up whether to take off her designer dress, and Ursula would have had to calculate whether the potential danger to her was worth the risk, given that she has three children of her own.’

‘That’s so unfair!’ Manon said, but he could detect the slightest warble of laughter in her voice that acknowledged the accuracy of his sketches.

‘And Leonora?’ she asked.

‘Oh God, Leonora! You don’t think she’s after me, do you?’ he asked.

Manon’s sudden peal of laughter turned the inside of the car momentarily into a bubble of happiness, but he didn’t know whether she was laughing because the suggestion was so preposterous, or because it was true.

‘Are you looking forward to this evening?’ he asked.

‘Not really.’

‘Me neither.’ But he found he was smiling at the road. ‘I think it was a good thing to do though, don’t you?’ he asked.

‘Penny would have liked it,’ Manon said.

She knew the subtext of his question without him having to bring up Penny’s name again.

‘Yes.’

‘She was someone who joined in,’ Manon said.

They were not, she was saying. It was something they had in common.

The silence that followed was easier, as if they were both comfortably lost in their thoughts. Several miles passed without him even being aware that he was driving. He was getting to know the route so well.

‘When you think about her, do you remember her before she was ill?’ he suddenly asked Manon and then wished he had resisted. The barrier between them came down again.

‘Of course,’ she said, in a clipped voice.

He gripped the steering wheel.

Then, suddenly, as if regretting her bluntness, she turned her head and looked at the side of his face. He could almost feel the thoughts rolling through her head as she understood what he had been asking.

‘I think about her in the last few weeks too,’ she said, kindly, ‘but I don’t think that was really her.’

‘Don’t you?’ It was a plea more than a question.

In the month before she died, the secondary tumour that had grown in Penny’s brain changed her personality completely. She became angry and towards the end almost violent, lashing out at him and her children whose futures had been denied her. The only person she had been able to tolerate in her presence was Manon.

Roy had been torn between Penny’s unspoken wish to die in Joshua Street, and her spoken wish, her first and immediate reaction to being told of the brain tumour, not to let her

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher