![Wild Awake]()

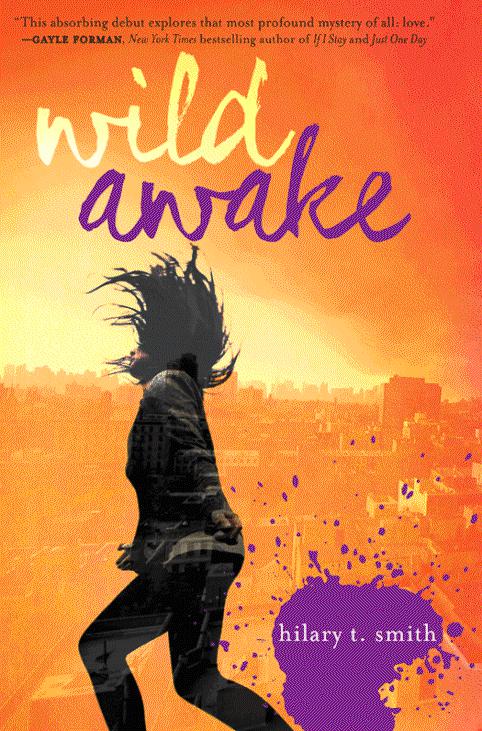

Wild Awake

working on a big painting ever since she moved in, and was already talking to some underground gallery about showing it when it was done. We hadn’t been to any more of her openings since the one at razzle!dazzle!space, but maybe Mom and Dad would let me come to this one. Denny could drive me; he was sixteen. Sukey promised she’d let me know as soon as she found out when it was going to be.

“I’ve been working on a very avant-garde composition,” I informed her, pronouncing it avant-grad .

Sukey laughed, a slow-motion twinkling of the vocal cords. I had a garage-sale Casio keyboard then, not even a real piano, and I was always making up songs with dramatic titles like “Heartstorm” or “Prelude for a Broken Wing.”

“You gonna play it for me before I leave?” she said.

I shook my head.

“Come on, Kiri-bird. I don’t know when Dad’s going to let me see you again.”

Technically, Sukey was banned from even visiting our house after Dad found out she’d stolen some money last time she was here—for paint, Sukey told me. For jars of gold and arsenic and ochre. This birthday visit had taken some high-octane pleading on my part, and even then Sukey was only allowed in the kitchen and living room and not upstairs.

“It’s not finished yet,” I said.

Just then, Dad appeared to let Sukey know it was time for her to go home, which was no longer the same thing as our home.

“Can’t she stay for dinner?” I said, playing the birthday card for all it was worth.

“That’s okay, babe, I have to get going anyway,” said Sukey, which probably meant she was fiending for a cigarette. “But let me give you your present.”

I fidgeted with anticipation, wishing Dad would leave the room. He was standing there with his hairy arms crossed, watching her warily, like he thought she was going to give me something inappropriate he was going to make her take right back—birth control pills or a stolen piece of jewelry.

“I didn’t have time to wrap it,” Sukey said, pulling something out of her bag, but when I saw what it was, I was too happy to care. It was one of her bird paintings—she’d done this matching pair while she still lived here, and I’d been begging her to let me have one forever. The one she gave me had the words we gamboled, star-clad spiraling out over the birds in silver paint. The other one said, simply, daffodiliad .

“You’re the BEST!” I kept saying over and over as I danced around the kitchen with the painting in my hands. I was still squealing my thanks when Mom came downstairs to talk to Sukey—or try to—before she left.

I didn’t open the card taped to the back of the painting until after Sukey was gone. It said:

Hey, k-bird. Hang this in your room, and I’ll keep the other one hanging in my studio. Be cool and don’t be a faker. Love, S .

For the next few weeks, I worked furiously on my new composition. Hunched over my keyboard, I made up strange chords, bold rhythms, soaring melodies. Maybe I could play it at Sukey’s art opening—we could even put my name on the card, feat. kiri byrd on keyboard .

I called and called Sukey’s cell phone to tell her about this idea, but she must have lost it on the beach again, because she didn’t pick up. Mom said not to worry; Sukey would call me back soon. I lay on my bed planning the details of our show: the crackers and lemonade, the clothes we’d wear.

When she died, it was like my house burned down.

chapter seven

The next morning I dress carefully , putting on ripped jeans, a vintage blouse, and the dangly beaded earrings that used to belong to Sukey and that have lived on my dresser ever since. If Doug Fieldgrass was calling from razzle!dazzle!space, he’s probably the curator. I want to look hip and mature and artistic when I meet him; I want to look like Sukey.

Why’s the gallery closing? I’ll ask sympathetically. It’s such an interesting space .

I try Doug’s number three times, but he doesn’t answer. I sit at the piano, telling myself to be patient, but after practicing for ten minutes, I decide to ride my bike downtown anyway. Maybe he’ll be at the gallery, and if he isn’t, at least I’ll know where it is for next time.

In daylight, Columbia Street seems way less sketchy. The Chinese grocery store is open, and there are wooden trucks of produce out on the sidewalk in front of it, long, hairy daikon radishes and bundles of bok choy and mountains of tangerines for fifty-nine cents a

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher