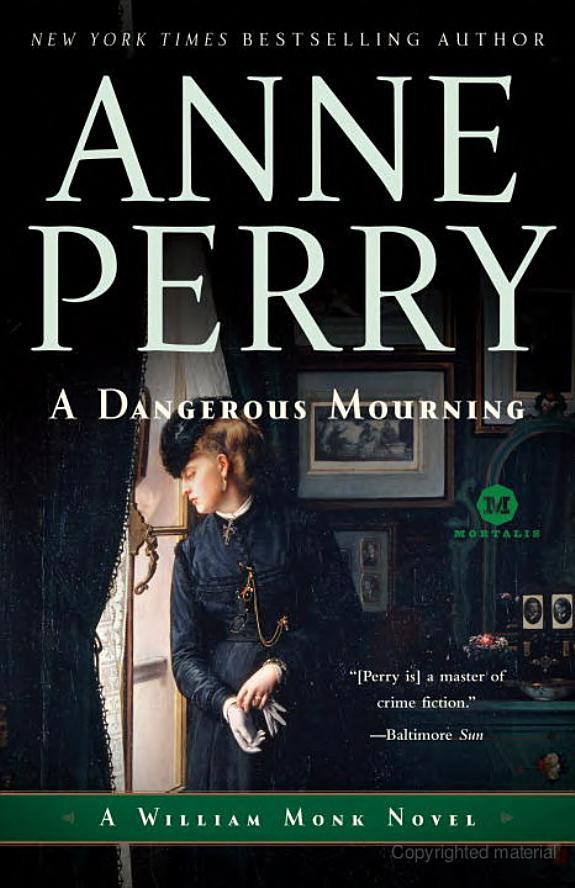

![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

sometimes feared senior policeman, good at his job, secure in his reputation and his skill. Now he was a man without work, without position, and in a short while he would be without money. And over Percival.

No—over the hatred between Runcorn and himself over the years, the rivalry, the fear, the misunderstandings.

Or perhaps over innocence and guilt?

9

M

ONK SLEPT POORLY

and woke late and heavy-headed. He rose and was half dressed before he remembered that he had nowhere to go. Not only was he off the Queen Anne Street case, he was no longer a policeman. In fact he was nothing. His profession was what had given him purpose, position in the community, occupation for his time, and now suddenly desperately important, his income. He would be all right for a few weeks, at least for his lodgings and his food. There would be no other expenditures, no clothes, no meals out, no new books or rare, wonderful visits to theater or gallery in his steps towards being a gentleman.

But those things were trivial. The center of his life had fallen out. The ambition he had nourished and sacrificed for, disciplined himself towards for all the lifetime he could remember or piece together from records and other people’s words, that was gone. He had no other relationships, nothing else he knew to do with his time, no one else who valued him, even if it was with admiration and fear, not love. He remembered sharply the faces of the men outside Runcorn’s door. There was confusion in them, embarrassment, anxiety—but not sympathy. He had earned their respect, but not their affection.

He felt more bitterly alone, confused, and wretched than at any time since the climax of the Grey case. He had no appetite for the breakfast Mrs. Worley brought him and ate only a rasher of bacon and two slices of toast. He was still looking at the crumb-scattered plate when there was a sharp rap on thedoor and Evan came in without waiting to be invited. He stared at Monk and sat down astride the other hard-backed chair and said nothing, his face full of anxiety and something so painfully gentle it could only be called compassion.

“Don’t look like that!” Monk said sharply. “I shall survive. There is life outside the police force, even for me.”

Evan said nothing.

“Have you arrested Percival?” Monk asked him.

“No. He sent Tarrant.”

Monk smiled sourly. “Perhaps he was afraid you wouldn’t do it. Fool!”

Evan winced.

“I’m sorry,” Monk apologized quickly. “But your resigning as well would hardly help—either Percival or me.”

“I suppose not,” Evan conceded ruefully, a shadow of guilt still lingering in his eyes. Monk seldom remembered how young he was, but now he looked every inch the country parson’s son with his correct casual clothes and his slightly different manner concealing an inner certainty Monk himself would never have. Evan might be more sensitive, less arrogant or forceful in his judgment, but he would always have a kind of ease because he was born a minor gentleman, and he knew it, if not on the surface of his mind, then in the deeper layer from which instinct springs. “What are you going to do now, have you thought? The newspapers are full of it this morning.”

“They would be,” Monk acknowledged. “Rejoicing everywhere, I expect? The Home Office will be praising the police, the aristocracy will be congratulating itself it is not at fault—it may have hired a bad footman, but that kind of misjudgment is bound to happen from time to time.” He heard the bitterness in his voice and despised it, but he could not remove it, it was too high in him. “Any honest gentleman can think too well of someone. Moidore’s family is exonerated. And the public at large can sleep safe in its beds again.”

“About right,” Evan conceded, pulling a face. “There’s a long editorial in the

Times

on the efficiency of the new police force, even in the most trying and sensitive of cases, to wit-in the very home of one of London’s most eminent gentlemen. Runcorn is mentioned several times as being in charge of the investigation. You aren’t mentioned at all.” He shrugged. “Neither am I.”

Monk smiled for the first time, at Evan’s innocence.

“There’s also a piece by someone regretting the rising arrogance of the working classes,” Evan went on. “And predicting the downfall of the social order as we know it and the general decline of Christian morals.”

“Naturally,” Monk said

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher