![William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning]()

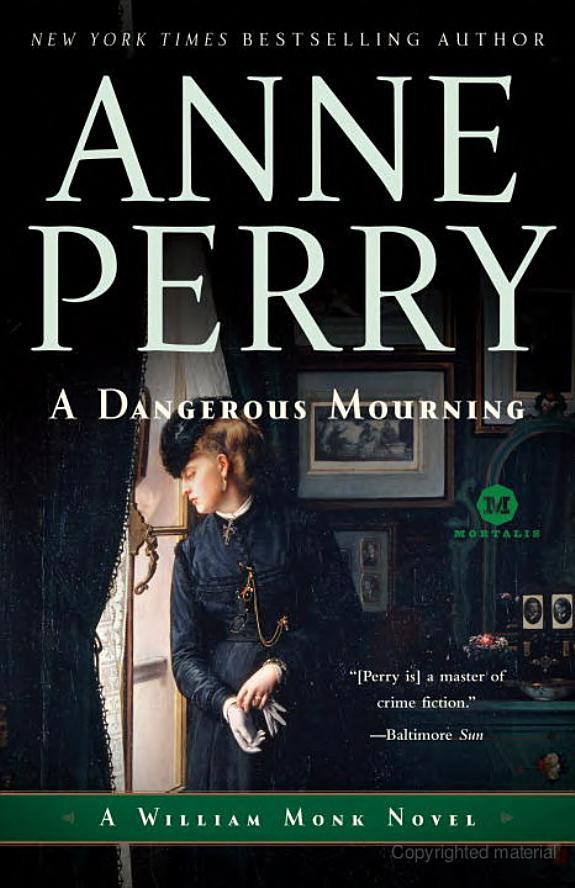

William Monk 02 - A Dangerous Mourning

invention which was much better than the old pulling carts, and which was causing something of a stir—and accompanied by a small, self-conscious boy with a hoop.

“She never even considered remarrying,” Romola went on without being asked, and having regarded the perambulator with due interest. “Of course it was only a little over two years, but Sir Basil did approach the subject. She was a young woman, and still without children. It would not be unseemly.”

Monk remembered the dead face he had seen that first morning. Even through the stiffness and the pallor he had imagined something of what she must have been like: the emotions, the hungers and the dreams. It was a face of passion and will.

“She was very comely?” He made it a question, although there was no doubt in his mind.

Romola hesitated, but there was no meanness in it, only a genuine doubt.

“She was handsome,” she said slowly. “But her chief quality was her vividness, and her complete individuality. After Harry died she became very moody and suffered”—she avoided his eyes—“suffered a lot of poor health. When shewas well she was quite delightful, everyone found her so. But when she was …” Again she stopped momentarily and searched for the word. “When she was poorly she spoke little—and made no effort to charm.”

Monk had a brief vision of what it must be like to be a woman on her own, obliged to work at pleasing people because your acceptance, perhaps even your financial survival, depended upon it. There must be hundreds—thousands—of petty accommodations, suppressions of your own beliefs and opinions because they would not be what someone else wished to hear. What a constant humiliation, like a burning blister on the heel which hurt with every step.

And on the other hand, what a desperate loneliness for a man if he ever realized he was always being told not what she really thought or felt but what she believed he wanted to hear. Would he then ever trust anything as real, or of value?

“Mr. Monk.”

She was speaking, and his concentration had left her totally.

“Yes ma’am—I apologize—”

“You asked me about Octavia. I was endeavoring to tell you.” She was irritated that he was so inattentive. “She was most appealing, at her best, and many men had called upon her, but she gave none of them the slightest encouragement. Whoever it was who killed her, I do not think you will find the slightest clue to their identity along that line of inquiry.”

“No, I imagine you are right. And Mr. Haslett died in the Crimea?”

“Captain Haslett. Yes.” She hesitated, looking away from him again. “Mr. Monk.”

“Yes ma’am?”

“It occurs to me that some people—some men—have strange ideas about women who are widowed—” She was obviously most uncomfortable about what it was she was attempting to say.

“Indeed,” he said encouragingly.

The wind caught at her bonnet, pulling it a little sideways, but she disregarded it. He wondered if she was trying to find a way to say what Sir Basil had prompted, and if the words would be his or her own.

Two little girls in frilled dresses passed by with their governess,walking very stiffly, eyes ahead as if unaware of the soldier coming the other way.

“It is not impossible that one of the servants, one of the men, entertained such—such ludicrous ideas—and became overfamiliar.”

They had almost stopped. Romola poked at the ground with the ferrule of her umbrella.

“If—if that happened, and she rebuffed him soundly—possibly he became angry—incensed—I mean …” She tailed off miserably, still avoiding looking at him.

“In the middle of the night?” he said dubiously. “He was certainly extremely bold to go to her bedroom and try such a thing.”

The color burned up her cheeks.

“Someone did,” she pointed out with a catch in her voice, still staring at the ground. “I know it seems preposterous. Were she not dead, I should laugh at it myself.”

“You are right,” he said reluctantly. “Or it may be that she discovered some secret that could have ruined a servant had she told it, and they killed her to prevent that.”

She looked up at him, her eyes wide. “Oh—yes, I suppose that sounds … possible. What kind of a secret? You mean dishonesty—immorality? But how would Tavie have learned of it?”

“I don’t know. Have you no idea where she went that afternoon?” He began to walk again, and she accompanied

Weitere Kostenlose Bücher